Volume 7, Issue 1 (1-2022)

CJHR 2022, 7(1): 5-14 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ariyazangane E, Borna M R, Johari Fard R. Relation of Anger Rumination and Self-Criticism with Social Maladjustment with the Mediating Role of Psychological Flexibility in Adolescent Boys and Girls. CJHR 2022; 7 (1) :5-14

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-212-en.html

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-212-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. , mohamrbr@gmail.com

2- Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. , mohamrbr@gmail.com

Full-Text [PDF 802 kb]

(474 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1092 Views)

Full-Text: (681 Views)

1. Introduction

The capacity to adjust plays a crucial role in human mental and physical health. Adjustment is defined as an individual’s effort to cope with and survive in the social and physical environment [1]. As social creatures, humans have always sought to learn skills to communicate with others in order to adjust to the environment. Adjustment is an intrinsic psychological tendency to cope with life challenges and a dynamic movement that deals with a person’s response to the environment and the changes occurring in it [2]. Social adjustment is an effective and efficient human behavior in adapting to the physical and mental environment. The mainstay of social adjustment is to create a balance between one’s wishes and the criticisms of society which can affect all dimensions of a person’s life [3].

Social adjustment plays an important role in the quality of students’ academic performance and achievements [4]. There is a significant positive relationship between social adjustment and academic performance of students [5]. According to developmental psychologists, social development affects not only adjustment with those the person is in contact with, but also their occupational and academic success. One of the objectives of education is to provide suitable conditions for achieving the highest level of academic achievement. Therefore, if students lack a desirable social status among their classmates, their academic achievement and knowledge acquisition will be disrupted [6]. Consequently, knowledge of the various components related to social adjustment and the way they exert their influence is one of the most important issues in psychology.

One of the variables affecting social maladjustment is anger rumination [7]. Anger is an important and effective emotion in people’s lives. It is caused by a person’s reaction to others’ inappropriate behaviors [8, 9]. As a type of obsessive rumination, anger rumination expresses thoughts that tend to be repetitive and focus on anger and, even in the absence of immediate and necessary environmental stimuli, reappear involuntarily. Even if they are internal, these repetitive thoughts still increase hostility in people and seriously damage their function in interpersonal and communication situations and their social adjustment function in different family, academic and occupational situations [10]. Continuous anger rumination deprives the individual of the opportunity to use social support, problem-solving skills, self-relaxation techniques, skills to maintain internal mastery and effective sense of humor, conversation, negotiation and effective communication. It also causes social maladjustment in the individual, the outcome of which is that either others avoid him/her or the individual feels redoubled anger, isolates himself/herself from others, or seeks seclusion [11].

Another component related to interpersonal relationships and social adjustment is self-criticism. High levels of self-criticism are related to a broad spectrum of psychological disorders which can cause and boost anger, anxiety, social avoidance, delinquency, personality disorders, interpersonal problems and ultimately social maladjustment [12]. Self-criticism is considered a form of self-persecution which causes stress and self-enfeeblement. It is defined as having high expectations for ourselves and making attempts to progress. Self-critical individuals become vulnerable when they face obstacles in achieving their goals. They become prone to feelings of depression along with extreme humiliation, guilt, worthlessness and failure when they fail to achieve the expected standards [13]. Consequently, they cannot manifest their communicational skills and abilities well and either gradually keep a distance from the society or feel angry. In both cases, their social function is damaged and social maladjustment will be observed in them [14].

People’s ability to handle the situation in stressful or uncomfortable conditions in the framework of a construct called psychological flexibility is another important factor which can affect and improve their social actions [15, 16]. Psychological flexibility enables individuals to act appropriately and effectively when facing pressures, challenges and other emotional and social problems. It is defined as the ability levels of people to adapt their cognition and behavior to changes in their environment [17, 18]. In social relations, people encounter conditions that, at times, may impair their ability to adapt socially. Under such conditions, those with higher levels of psychological flexibility attempt to rectify social reactions by managing the situation [19]. People who enjoy psychological flexibility are not only able to develop self-mastery but also can resolve issues by understanding and overcoming them using problem-solving interventions that conform to social requirements as this conformity is necessary for attaining social adjustment.

While examining the relationships between the mentioned variables, this study considered the differences between the male and female students. The difference in gender roles is a major lived experience of boys and girls which is found in every society and culture. The division of gender roles begins in childhood in the socialization process and is manifested in all dimensions of life. Generally speaking, gender roles refer to the behavioral norms generally considered appropriate according to the norms of society. Based on the interactive model of gender-related behavior, gender per se does not determine what types of behavior an individual can have or exhibit. Rather, it determines the expectations that both the individual and others have of his/her behavior. Therefore, gender stereotypically affects behavior, attitude, cognition and beliefs of girls and boys [20]. Accordingly, this study aimed to investigate the relation of anger rumination and self-criticism with social maladjustment with the mediating role of psychological flexibility in adolescent boys and girls.

2. Materials and Methods

Design and participants

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The statistical population was all secondary school students aged between 16 and 18 years old of Ahvaz in the 2020-21 academic year. Sample size was determined based on the rule of thumb of 10 cases per 78 variables, yielding a minimum sample size of 780 cases. The sample were selected using convenience sampling method. Four high schools (two girls’ and two boys’ high schools) in two out of the four districts in Ahvaz were selected. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and failure to have direct access to students, the questionnaires were completed online by participants through online class groups with the help of teachers. Two incomplete questionnaires were excluded, and the final sample consisted of 848 students (443 girls and 405 boys).

Instruments

Anger Rumination Scale (ARS), Levels of Self-Criticism Scale (LOSCS), Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II (AAQ-II), and Social Development Scale (SDS) were used to measure the study constructs. ARS was developed by Sukhodolsky et al. [21]. It consists of 19 items that measure a person’s tendency to focus on current angry moods and recall past episodes of anger. It is scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1= very low to 4= very high. A higher score indicates a higher level of anger rumination. The Persian version of ARS was validated by Mahmoudi et al. [22]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale was reported 0.85. LOSCS was developed by Thompson and Zuroff [23]. In this scale, two dimensions of Internal Self-Criticism (ISC) and Comparative Self-Criticism (CSC) are measured. It consists of 22 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0= never to 6= always true. The Persian version of the scale was validated by Mousavi and Ghorbani in 2006 [24]. Thompson and Zuroff [23] reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 for the total score. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.84 for the scale. AAQ-II is a self-report measure to assess psychological flexibility. The Persian version of the questionnaire was validated by Abasi et al. [25]. It consists of 10 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1= never true to 7= always true. Higher scores indicate greater psychological flexibility [26]. Abasi et al. [25]reported an alpha Cronbach coefficient of 0.80 for the questionnaire. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.73 for the questionnaire. SDS was developed by Witsman in 1960 to determine social development of adolescents between 13 and 18 years old. The SDS, was used to determine social development of the adolescents and measures six components of cooperation, good mood and adaptability, respect for others / responsibility, hope, optimism and patience. It consists of 27 items with 3 or 4 answer choices for each one. The minimum and maximum scores obtainable on this scale are 0 and 25, respectively. A score between 0 and 4 indicates weak social development, a score between 5 and 14 indicates moderate social development, and a score between 15 and 25 indicates strong social development. In the current study, the Persian version of the scale was used. Rahdar et al. [27] reported an alpha Cronbach coefficient of 0.70 for the scale. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.71 for the scale.

Statistical analyses

Prior to testing the model, the four assumptions of the structural equations including missing data, outliers, normality, and multicollinearity were examined. As the questionnaires were filled online, and the need to answer all questions, there were no missing data. The outliers were examined using the Mahalanobis distance. Skewness and kurtosis were used to examine the normality, and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and tolerance were used to measure multicollinearity. A hypothetical model was proposed by incorporating the concepts of the mediating role of psychological flexibility in the relationship of anger rumination and self-criticism with social maladjustment. The fit of the proposed model was assessed using the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), and the Root Means Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). The bootstrap method was used to test the indirect effects. The difference between boys and girls was tested using multigroup SEM. A Critical Ratio (C.R.) beyond -1.96 and +1.96 was considered as the statistical limit to reject the null hypothesis of no difference between boys and girls. Data were analyzed in SPSS version 24 and the SEM was performed in the Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) software version 24.

3. Results

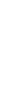

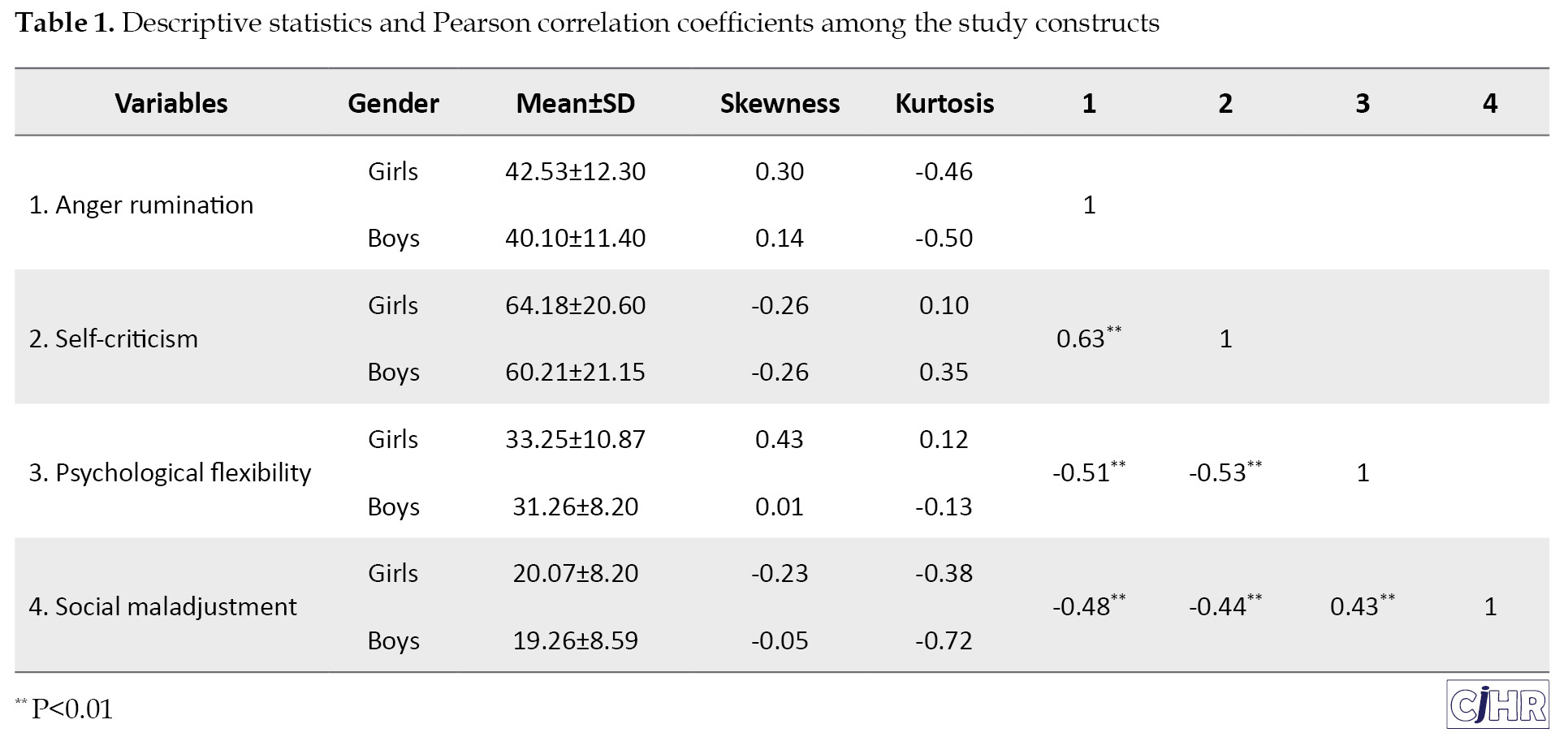

In this study, 52.2% of the participants were girls (n=443) and 47.7% were boys (n=405). A total of 506 students were in the 10th grade (59.6%), 171 in the 11th grade (20.2%) and 171 in the 12th grade (20.2%). The students were between 15 and 17 years old. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and correlation coefficient of the study constructs.

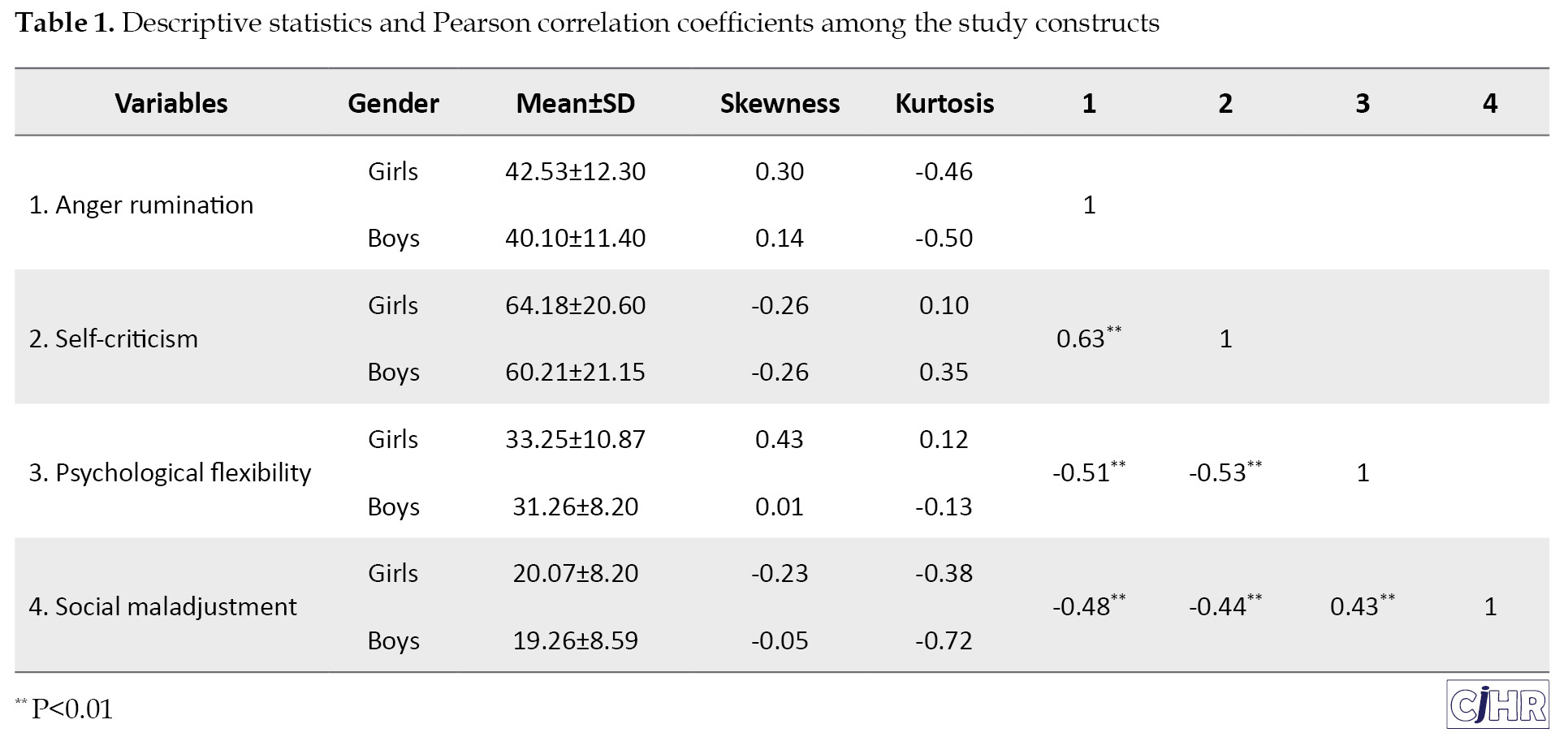

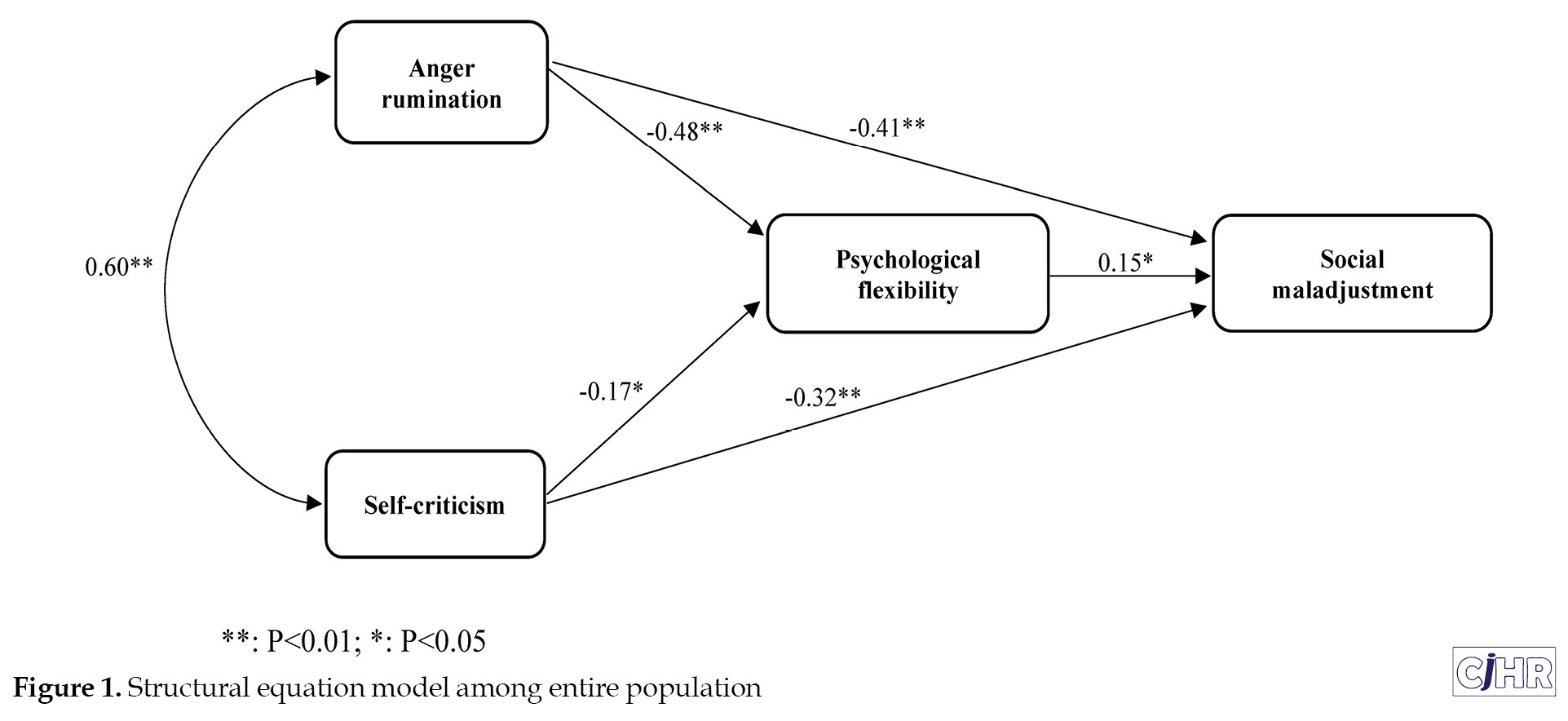

There was strong and direct correlation between anger rumination and self-criticism (r=0.63, P<0.01), and negative correlation between anger rumination and psychological flexibility (r=-0.51, P<0.01) and social maladjustment (r=-0.48, P<0.01). Figure 1 shows structural equation model of the study constructs with standardized coefficient and factor loading.

The final model has a good fit (χ2/df=2.82, GFI=0.97, IFI=0.95, CFI=0.95, and RMSEA=0.047). The results showed there was a direct relationship between psychological flexibility and social maladjustment in the students (β=0.15; P=0.016). There was a negative relationship between anger rumination and psychological flexibility (β=-0.48; P=0.001), and between anger rumination and social maladjustment in the students (β=-0.41; P=0.001). Moreover, there was a negative relationship between self-criticism and psychological flexibility (β=-0.17; P=0.012), and between self-criticism and social maladjustment in the students (β=-0.32; P=0.001).

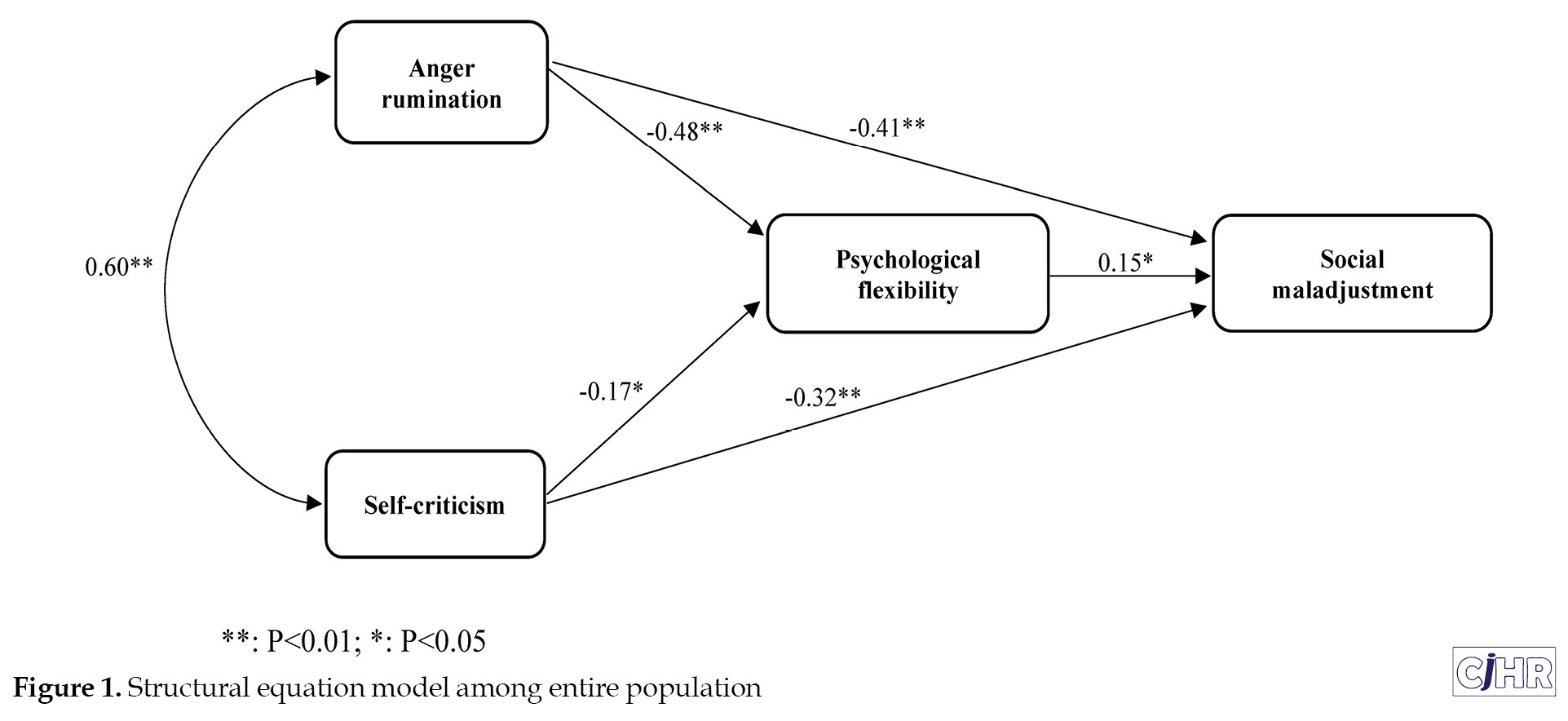

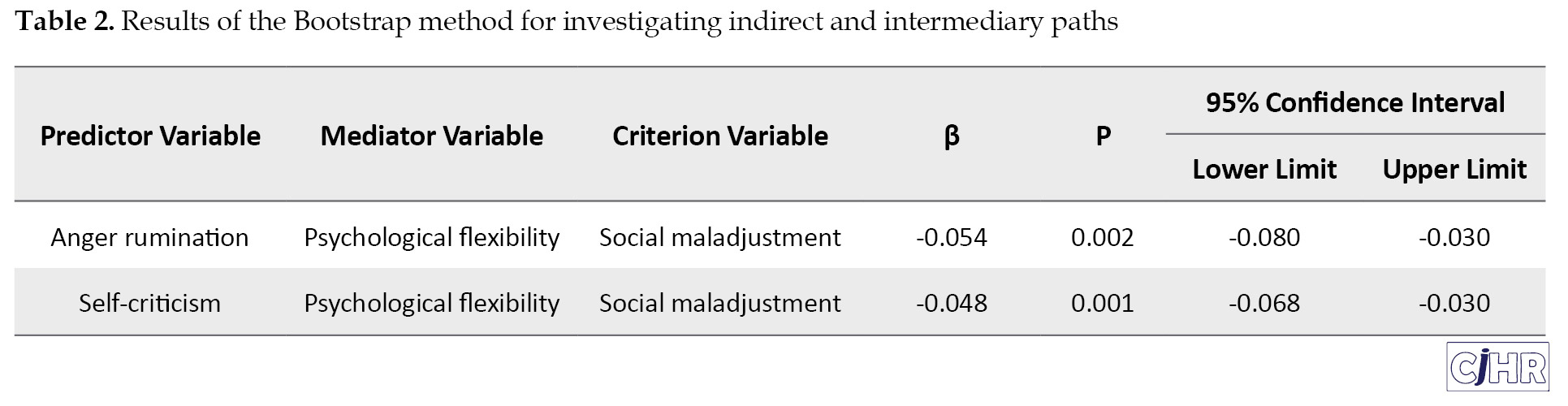

The results of bootstrapping for the mediating paths of the proposed model are shown in Table 2.

According to the results there was significant indirect paths of anger rumination and self-criticism to social maladjustment through psychological flexibility.

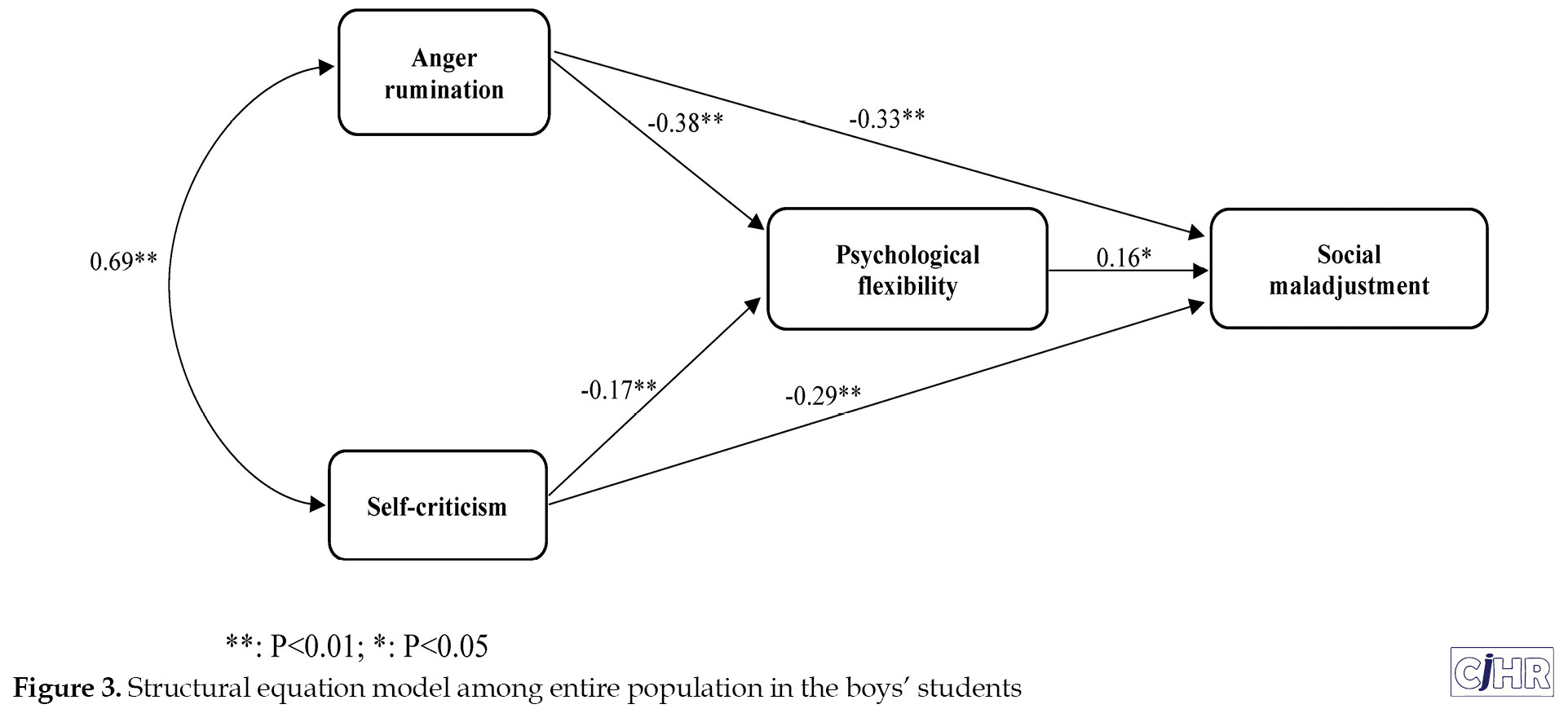

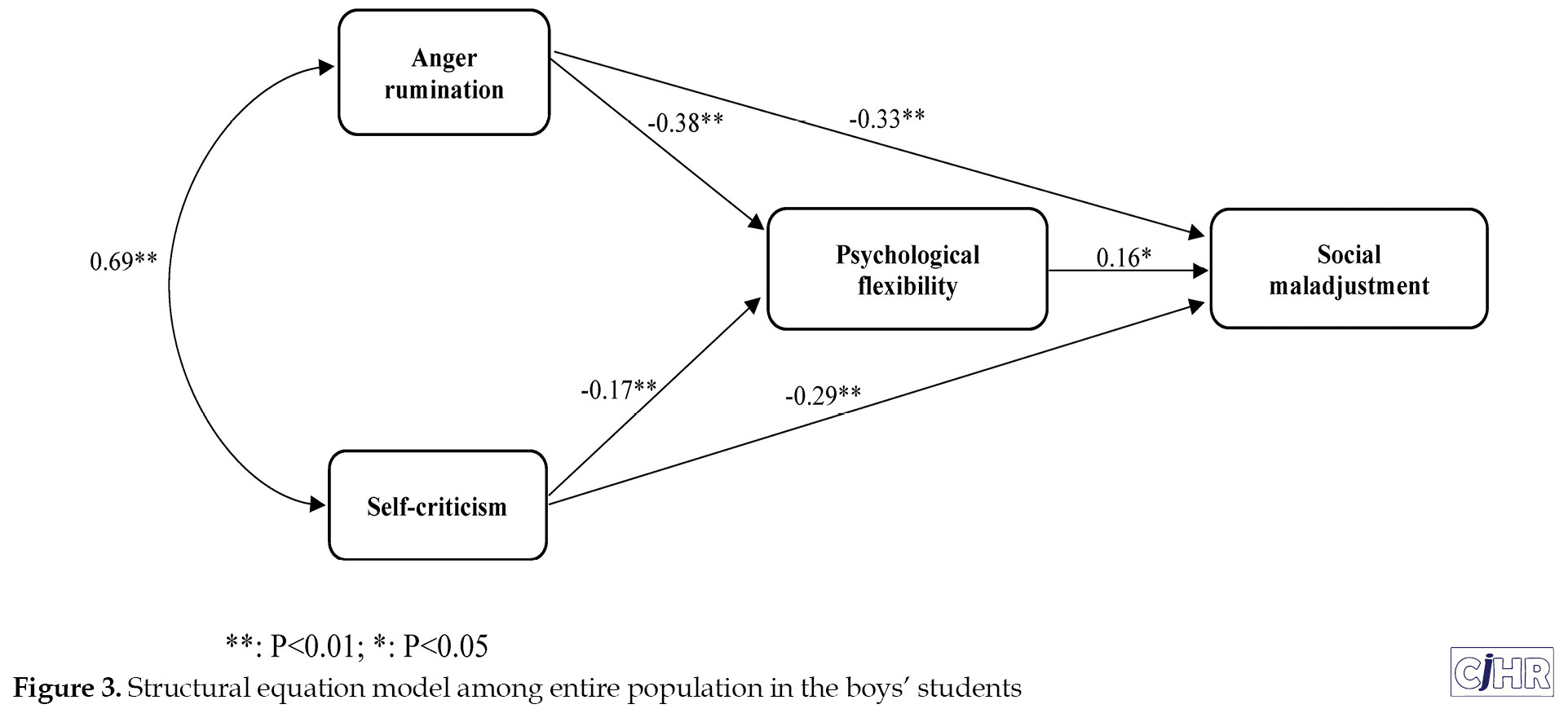

According to the result, both the unrestricted (χ2/df=2.20, GFI=0.92, IFI=0.94, CFI=0.94, and RMSEA=0.38) and the restricted (χ2/df=2.13, GFI=0.93, IFI=0.94, CFI=0.94, and RMSEA=0.38) models had good fit indices. The differences between the chi-squares and the degrees of freedom for the restricted and unrestricted models were 31.55 and 10, respectively, which were significant at P<0.01. Given the significance of the chi-square difference, it is concluded that both groups (the boys and the girls) had different regression weights. Figures 2 and 3 show multigroup analysis in the SEM among girls and boys, respectively.

The critical ratio for differences was calculated for the standardized path coefficients in the two models (the girls and the boys) for accurate pairwise comparison of similar path coefficients. The matrix comparing the standardized direct path coefficients in the two models is shown in Table 3.

According to the values of critical ratio the association of anger rumination and self-criticism with social maladjustment was significantly different between boys and girls. The inverse association of anger rumination to social maladjustment (B=-0.33) and Self-criticism to social maladjustment (B=-0.29) were only significant in boys.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the relation of anger rumination and self-criticism with social maladjustment with the mediating role of psychological flexibility in adolescent boys and girls in Ahvaz, Iran. The results showed a direct negative relationship between anger rumination and psychological flexibility. In line with the findings of Eifert and Forsyth [28], people who experience anger are more likely to stick to anger-triggering thoughts i.e., anger rumination and feeling of inability in control of anger. Therefore, they lack the required ability to respond to the environment according to the conditions; therefore, they experience low levels of psychological flexibility. Anger rumination, which is constantly thinking about anger and not avoiding or inhibiting it, prevents processing of adaptive information resulting from anger and learning that anger and other living conditions are not necessarily dangerous. Consequently, people who suffer from anger rumination cannot develop a suitable spectrum of the required behaviors for interpersonal functions [7]. As a result, they fail to show the required flexibility in their coping style in behavior due to anger rumination and the thoughts related to it.

In addition, the results showed a direct negative correlation between anger rumination and social maladjustment. This finding is consistent with previous studies carried out by Besharat et al. [29] and Barzegari Dehej et al. [30]. Besharat et al. [29] demonstrated that worry and anger rumination reduced people’s ability to adjust to stressful situations by making it difficult for them to regulate the emotions and feelings they experienced. Anger rumination is a cognitive-emotional process of repetitive thoughts about anger-triggering events that lead to prolonged stress. Consequently, it is accompanied by many maladaptive outcomes including physiological arousal, aggressive behavior, and decreased psychological well-being and use of ineffective strategies to deal with stressful situations, which boosts maladjusted behaviors in social situations.

Moreover, the results suggested a direct negative correlation between self-criticism and psychological flexibility. Dajani and Uddin [31] reported that intolerance of uncertainty, perfectionism and parental criticism reduced individuals’ cognitive flexibility and hence it was necessary to improve cognitive flexibility in students. As a component of self-criticism, comparative self-criticism focuses on inappropriate comparison of oneself with others who appear to be superior, hostile and critical, which eventually leads to disinclination to meet others and be assessed by them. Comparative self-criticism often accompanies interpersonal hostility, feelings of total inferiority and inability to overcome life problems. Therefore, these individuals act inflexibly and use avoidance to cope with problems. In internalized self-criticism, individuals have a negative attitude toward themselves due to comparing themselves with personal and internal standards. Since these standards are quite high, they cannot be fulfilled. This lack of fulfillment is regarded by a self-critical person as a weakness and defect. In these people, failure causes absolute worthlessness because they do not accept their defects in certain areas [13]. Therefore, they have a state of rigidity and cognitive inflexibility in relation to their standards and deal with failure or success in a negative and inefficient way.

The results of this study confirmed that there was a direct negative correlation between self-criticism and social maladjustment. This finding is consistent with the findings of studies carried out by Rajabi and Abasi [32]and Malekpour et al. [33]. Rajabi and Abasi [32] reported that self-criticism and anxiety that people showed in social situations caused internalized shame and affected their social behaviors. Malekpour et al. [33] found that self-absorption, maladaptive perfectionism and self-criticism were the major variables influencing development of depression in students, which prepared the ground for maladaptive behavior in various social situations. Self-critical individuals with low self-disclosure in their interpersonal relationships, are unfriendly in their close relationships and take less responsibility for their friends. They experience undesirable relationships in everyday life and hear themselves judged as being unlovable. Self-critical individuals seek to improve their social situation even at the expense of sacrificing their friends, and if their friends disagree with them, they seek to compensate it. These characteristics together reduce their adjustment and adaptability in various situations (for example, social situations).

The results of this study confirmed that there was a direct positive correlation between psychological flexibility and social maladjustment. This finding is consistent with previous study carried out by Hulbert-Williams et al [16]. When a crisis strikes, flexible people find safe and secure solutions by using problem-solving techniques. Others experience high levels of stress and cannot select an appropriate and useful solution. Flexible people have a strong supportive and emotional network which helps them talk to others about their worries and challenges, enjoy their consultation, empathy and companionship and discover new solutions and feel powerful and relaxed mentally. In fact, supportive resources are one of the major components of flexibility and flexible people ask for help from them whenever necessary [16]. These characteristics of flexible individuals help them maintain their social adjustment.

Regarding the indirect effects, the findings suggested that psychological flexibility played a mediating role in the relationships of anger rumination and self-criticism with social maladjustment. Therefore, anger rumination and self-criticism had a direct effect on social maladjustment of male and female adolescent students in Ahvaz through the mediating role of psychological flexibility.

The results of a simultaneous comparison between the models for the boy and the girls showed a significant difference between them. The results indicated that the direct paths of anger rumination and self-criticism to social maladjustment were significant just in boys. Gender difference in the relationship between anger rumination and social maladjustment has not explored yet. The significant association of anger rumination and social maladjustment in the boys could be attributed to the gender stereotypes governing the culture. Based on these gender stereotypes, anger and its manifestation in the form of aggression is more acceptable in boys than girls. On the other hand, girls are expected to control their emotions in anger-triggering situations and show it in a more peaceful way. Therefore, constant and repeated experience of anger is more expected in boys than girls and if they fail to express it, they will excessively and repeatedly think about it and experience higher levels of anger rumination. Therefore, it can be inferred that boys experience more social maladjustment than girls due to their more frequent experience of anger rumination.

In addition, no studies were found on the gender difference in association between self-criticism and social maladjustment. The stronger path of self-criticism to social maladjustment in the boys could be attributed to the social support they received from others. High levels of self-criticism mean limited relationships and social network as self-critical people have a more restricted social circle due to their pessimistic view of others. Although they have high levels of self-criticism, girls might experience lower social maladjustment compared to boys because they have better social relations and receive more social support from others.

The limitations of this research were the statistical population that was limited to high school students of Ahvaz, the limited ability of structural equations modeling in proving causality and the limitations related to the use of self-report questionnaires.

5. Conclusion

This study highlighted the importance of anger rumination, self-criticism and psychological flexibility in predicting social maladjustment in adolescents living in Ahvaz. Due to the negative impact of self-criticism on flexibility and adaptive behavior of students, it is recommended that they participate in workshops and courses on self-criticism. Increasing psychological flexibility and resilience in students may affect their social adjustment. Therefore, it is suggested that this variable be considered in the courses and workshops provided to them. Since, the knowledge and help of teachers, managers and parents can affect the efficiency of the courses, it is also suggested to provide them courses on the investigated variables. It is recommended that gender differences be considered when holding any of the mentioned workshops and training courses be designed and offered taking these differences into consideration.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The current study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University Ahvaz Branch. Iran (code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1399.120)

Funding

This article was extracted from the PhD dissertation of the first author in the Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran.

Authors' contributions

All authors have equally contributed in preparing the article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the individuals who participated in the research.

References

The capacity to adjust plays a crucial role in human mental and physical health. Adjustment is defined as an individual’s effort to cope with and survive in the social and physical environment [1]. As social creatures, humans have always sought to learn skills to communicate with others in order to adjust to the environment. Adjustment is an intrinsic psychological tendency to cope with life challenges and a dynamic movement that deals with a person’s response to the environment and the changes occurring in it [2]. Social adjustment is an effective and efficient human behavior in adapting to the physical and mental environment. The mainstay of social adjustment is to create a balance between one’s wishes and the criticisms of society which can affect all dimensions of a person’s life [3].

Social adjustment plays an important role in the quality of students’ academic performance and achievements [4]. There is a significant positive relationship between social adjustment and academic performance of students [5]. According to developmental psychologists, social development affects not only adjustment with those the person is in contact with, but also their occupational and academic success. One of the objectives of education is to provide suitable conditions for achieving the highest level of academic achievement. Therefore, if students lack a desirable social status among their classmates, their academic achievement and knowledge acquisition will be disrupted [6]. Consequently, knowledge of the various components related to social adjustment and the way they exert their influence is one of the most important issues in psychology.

One of the variables affecting social maladjustment is anger rumination [7]. Anger is an important and effective emotion in people’s lives. It is caused by a person’s reaction to others’ inappropriate behaviors [8, 9]. As a type of obsessive rumination, anger rumination expresses thoughts that tend to be repetitive and focus on anger and, even in the absence of immediate and necessary environmental stimuli, reappear involuntarily. Even if they are internal, these repetitive thoughts still increase hostility in people and seriously damage their function in interpersonal and communication situations and their social adjustment function in different family, academic and occupational situations [10]. Continuous anger rumination deprives the individual of the opportunity to use social support, problem-solving skills, self-relaxation techniques, skills to maintain internal mastery and effective sense of humor, conversation, negotiation and effective communication. It also causes social maladjustment in the individual, the outcome of which is that either others avoid him/her or the individual feels redoubled anger, isolates himself/herself from others, or seeks seclusion [11].

Another component related to interpersonal relationships and social adjustment is self-criticism. High levels of self-criticism are related to a broad spectrum of psychological disorders which can cause and boost anger, anxiety, social avoidance, delinquency, personality disorders, interpersonal problems and ultimately social maladjustment [12]. Self-criticism is considered a form of self-persecution which causes stress and self-enfeeblement. It is defined as having high expectations for ourselves and making attempts to progress. Self-critical individuals become vulnerable when they face obstacles in achieving their goals. They become prone to feelings of depression along with extreme humiliation, guilt, worthlessness and failure when they fail to achieve the expected standards [13]. Consequently, they cannot manifest their communicational skills and abilities well and either gradually keep a distance from the society or feel angry. In both cases, their social function is damaged and social maladjustment will be observed in them [14].

People’s ability to handle the situation in stressful or uncomfortable conditions in the framework of a construct called psychological flexibility is another important factor which can affect and improve their social actions [15, 16]. Psychological flexibility enables individuals to act appropriately and effectively when facing pressures, challenges and other emotional and social problems. It is defined as the ability levels of people to adapt their cognition and behavior to changes in their environment [17, 18]. In social relations, people encounter conditions that, at times, may impair their ability to adapt socially. Under such conditions, those with higher levels of psychological flexibility attempt to rectify social reactions by managing the situation [19]. People who enjoy psychological flexibility are not only able to develop self-mastery but also can resolve issues by understanding and overcoming them using problem-solving interventions that conform to social requirements as this conformity is necessary for attaining social adjustment.

While examining the relationships between the mentioned variables, this study considered the differences between the male and female students. The difference in gender roles is a major lived experience of boys and girls which is found in every society and culture. The division of gender roles begins in childhood in the socialization process and is manifested in all dimensions of life. Generally speaking, gender roles refer to the behavioral norms generally considered appropriate according to the norms of society. Based on the interactive model of gender-related behavior, gender per se does not determine what types of behavior an individual can have or exhibit. Rather, it determines the expectations that both the individual and others have of his/her behavior. Therefore, gender stereotypically affects behavior, attitude, cognition and beliefs of girls and boys [20]. Accordingly, this study aimed to investigate the relation of anger rumination and self-criticism with social maladjustment with the mediating role of psychological flexibility in adolescent boys and girls.

2. Materials and Methods

Design and participants

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). The statistical population was all secondary school students aged between 16 and 18 years old of Ahvaz in the 2020-21 academic year. Sample size was determined based on the rule of thumb of 10 cases per 78 variables, yielding a minimum sample size of 780 cases. The sample were selected using convenience sampling method. Four high schools (two girls’ and two boys’ high schools) in two out of the four districts in Ahvaz were selected. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic and failure to have direct access to students, the questionnaires were completed online by participants through online class groups with the help of teachers. Two incomplete questionnaires were excluded, and the final sample consisted of 848 students (443 girls and 405 boys).

Instruments

Anger Rumination Scale (ARS), Levels of Self-Criticism Scale (LOSCS), Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II (AAQ-II), and Social Development Scale (SDS) were used to measure the study constructs. ARS was developed by Sukhodolsky et al. [21]. It consists of 19 items that measure a person’s tendency to focus on current angry moods and recall past episodes of anger. It is scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1= very low to 4= very high. A higher score indicates a higher level of anger rumination. The Persian version of ARS was validated by Mahmoudi et al. [22]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale was reported 0.85. LOSCS was developed by Thompson and Zuroff [23]. In this scale, two dimensions of Internal Self-Criticism (ISC) and Comparative Self-Criticism (CSC) are measured. It consists of 22 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 0= never to 6= always true. The Persian version of the scale was validated by Mousavi and Ghorbani in 2006 [24]. Thompson and Zuroff [23] reported a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 for the total score. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.84 for the scale. AAQ-II is a self-report measure to assess psychological flexibility. The Persian version of the questionnaire was validated by Abasi et al. [25]. It consists of 10 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1= never true to 7= always true. Higher scores indicate greater psychological flexibility [26]. Abasi et al. [25]reported an alpha Cronbach coefficient of 0.80 for the questionnaire. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.73 for the questionnaire. SDS was developed by Witsman in 1960 to determine social development of adolescents between 13 and 18 years old. The SDS, was used to determine social development of the adolescents and measures six components of cooperation, good mood and adaptability, respect for others / responsibility, hope, optimism and patience. It consists of 27 items with 3 or 4 answer choices for each one. The minimum and maximum scores obtainable on this scale are 0 and 25, respectively. A score between 0 and 4 indicates weak social development, a score between 5 and 14 indicates moderate social development, and a score between 15 and 25 indicates strong social development. In the current study, the Persian version of the scale was used. Rahdar et al. [27] reported an alpha Cronbach coefficient of 0.70 for the scale. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.71 for the scale.

Statistical analyses

Prior to testing the model, the four assumptions of the structural equations including missing data, outliers, normality, and multicollinearity were examined. As the questionnaires were filled online, and the need to answer all questions, there were no missing data. The outliers were examined using the Mahalanobis distance. Skewness and kurtosis were used to examine the normality, and the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) and tolerance were used to measure multicollinearity. A hypothetical model was proposed by incorporating the concepts of the mediating role of psychological flexibility in the relationship of anger rumination and self-criticism with social maladjustment. The fit of the proposed model was assessed using the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Incremental Fit Index (IFI), and the Root Means Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA). The bootstrap method was used to test the indirect effects. The difference between boys and girls was tested using multigroup SEM. A Critical Ratio (C.R.) beyond -1.96 and +1.96 was considered as the statistical limit to reject the null hypothesis of no difference between boys and girls. Data were analyzed in SPSS version 24 and the SEM was performed in the Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) software version 24.

3. Results

In this study, 52.2% of the participants were girls (n=443) and 47.7% were boys (n=405). A total of 506 students were in the 10th grade (59.6%), 171 in the 11th grade (20.2%) and 171 in the 12th grade (20.2%). The students were between 15 and 17 years old. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and correlation coefficient of the study constructs.

There was strong and direct correlation between anger rumination and self-criticism (r=0.63, P<0.01), and negative correlation between anger rumination and psychological flexibility (r=-0.51, P<0.01) and social maladjustment (r=-0.48, P<0.01). Figure 1 shows structural equation model of the study constructs with standardized coefficient and factor loading.

The final model has a good fit (χ2/df=2.82, GFI=0.97, IFI=0.95, CFI=0.95, and RMSEA=0.047). The results showed there was a direct relationship between psychological flexibility and social maladjustment in the students (β=0.15; P=0.016). There was a negative relationship between anger rumination and psychological flexibility (β=-0.48; P=0.001), and between anger rumination and social maladjustment in the students (β=-0.41; P=0.001). Moreover, there was a negative relationship between self-criticism and psychological flexibility (β=-0.17; P=0.012), and between self-criticism and social maladjustment in the students (β=-0.32; P=0.001).

The results of bootstrapping for the mediating paths of the proposed model are shown in Table 2.

According to the results there was significant indirect paths of anger rumination and self-criticism to social maladjustment through psychological flexibility.

According to the result, both the unrestricted (χ2/df=2.20, GFI=0.92, IFI=0.94, CFI=0.94, and RMSEA=0.38) and the restricted (χ2/df=2.13, GFI=0.93, IFI=0.94, CFI=0.94, and RMSEA=0.38) models had good fit indices. The differences between the chi-squares and the degrees of freedom for the restricted and unrestricted models were 31.55 and 10, respectively, which were significant at P<0.01. Given the significance of the chi-square difference, it is concluded that both groups (the boys and the girls) had different regression weights. Figures 2 and 3 show multigroup analysis in the SEM among girls and boys, respectively.

The critical ratio for differences was calculated for the standardized path coefficients in the two models (the girls and the boys) for accurate pairwise comparison of similar path coefficients. The matrix comparing the standardized direct path coefficients in the two models is shown in Table 3.

According to the values of critical ratio the association of anger rumination and self-criticism with social maladjustment was significantly different between boys and girls. The inverse association of anger rumination to social maladjustment (B=-0.33) and Self-criticism to social maladjustment (B=-0.29) were only significant in boys.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the relation of anger rumination and self-criticism with social maladjustment with the mediating role of psychological flexibility in adolescent boys and girls in Ahvaz, Iran. The results showed a direct negative relationship between anger rumination and psychological flexibility. In line with the findings of Eifert and Forsyth [28], people who experience anger are more likely to stick to anger-triggering thoughts i.e., anger rumination and feeling of inability in control of anger. Therefore, they lack the required ability to respond to the environment according to the conditions; therefore, they experience low levels of psychological flexibility. Anger rumination, which is constantly thinking about anger and not avoiding or inhibiting it, prevents processing of adaptive information resulting from anger and learning that anger and other living conditions are not necessarily dangerous. Consequently, people who suffer from anger rumination cannot develop a suitable spectrum of the required behaviors for interpersonal functions [7]. As a result, they fail to show the required flexibility in their coping style in behavior due to anger rumination and the thoughts related to it.

In addition, the results showed a direct negative correlation between anger rumination and social maladjustment. This finding is consistent with previous studies carried out by Besharat et al. [29] and Barzegari Dehej et al. [30]. Besharat et al. [29] demonstrated that worry and anger rumination reduced people’s ability to adjust to stressful situations by making it difficult for them to regulate the emotions and feelings they experienced. Anger rumination is a cognitive-emotional process of repetitive thoughts about anger-triggering events that lead to prolonged stress. Consequently, it is accompanied by many maladaptive outcomes including physiological arousal, aggressive behavior, and decreased psychological well-being and use of ineffective strategies to deal with stressful situations, which boosts maladjusted behaviors in social situations.

Moreover, the results suggested a direct negative correlation between self-criticism and psychological flexibility. Dajani and Uddin [31] reported that intolerance of uncertainty, perfectionism and parental criticism reduced individuals’ cognitive flexibility and hence it was necessary to improve cognitive flexibility in students. As a component of self-criticism, comparative self-criticism focuses on inappropriate comparison of oneself with others who appear to be superior, hostile and critical, which eventually leads to disinclination to meet others and be assessed by them. Comparative self-criticism often accompanies interpersonal hostility, feelings of total inferiority and inability to overcome life problems. Therefore, these individuals act inflexibly and use avoidance to cope with problems. In internalized self-criticism, individuals have a negative attitude toward themselves due to comparing themselves with personal and internal standards. Since these standards are quite high, they cannot be fulfilled. This lack of fulfillment is regarded by a self-critical person as a weakness and defect. In these people, failure causes absolute worthlessness because they do not accept their defects in certain areas [13]. Therefore, they have a state of rigidity and cognitive inflexibility in relation to their standards and deal with failure or success in a negative and inefficient way.

The results of this study confirmed that there was a direct negative correlation between self-criticism and social maladjustment. This finding is consistent with the findings of studies carried out by Rajabi and Abasi [32]and Malekpour et al. [33]. Rajabi and Abasi [32] reported that self-criticism and anxiety that people showed in social situations caused internalized shame and affected their social behaviors. Malekpour et al. [33] found that self-absorption, maladaptive perfectionism and self-criticism were the major variables influencing development of depression in students, which prepared the ground for maladaptive behavior in various social situations. Self-critical individuals with low self-disclosure in their interpersonal relationships, are unfriendly in their close relationships and take less responsibility for their friends. They experience undesirable relationships in everyday life and hear themselves judged as being unlovable. Self-critical individuals seek to improve their social situation even at the expense of sacrificing their friends, and if their friends disagree with them, they seek to compensate it. These characteristics together reduce their adjustment and adaptability in various situations (for example, social situations).

The results of this study confirmed that there was a direct positive correlation between psychological flexibility and social maladjustment. This finding is consistent with previous study carried out by Hulbert-Williams et al [16]. When a crisis strikes, flexible people find safe and secure solutions by using problem-solving techniques. Others experience high levels of stress and cannot select an appropriate and useful solution. Flexible people have a strong supportive and emotional network which helps them talk to others about their worries and challenges, enjoy their consultation, empathy and companionship and discover new solutions and feel powerful and relaxed mentally. In fact, supportive resources are one of the major components of flexibility and flexible people ask for help from them whenever necessary [16]. These characteristics of flexible individuals help them maintain their social adjustment.

Regarding the indirect effects, the findings suggested that psychological flexibility played a mediating role in the relationships of anger rumination and self-criticism with social maladjustment. Therefore, anger rumination and self-criticism had a direct effect on social maladjustment of male and female adolescent students in Ahvaz through the mediating role of psychological flexibility.

The results of a simultaneous comparison between the models for the boy and the girls showed a significant difference between them. The results indicated that the direct paths of anger rumination and self-criticism to social maladjustment were significant just in boys. Gender difference in the relationship between anger rumination and social maladjustment has not explored yet. The significant association of anger rumination and social maladjustment in the boys could be attributed to the gender stereotypes governing the culture. Based on these gender stereotypes, anger and its manifestation in the form of aggression is more acceptable in boys than girls. On the other hand, girls are expected to control their emotions in anger-triggering situations and show it in a more peaceful way. Therefore, constant and repeated experience of anger is more expected in boys than girls and if they fail to express it, they will excessively and repeatedly think about it and experience higher levels of anger rumination. Therefore, it can be inferred that boys experience more social maladjustment than girls due to their more frequent experience of anger rumination.

In addition, no studies were found on the gender difference in association between self-criticism and social maladjustment. The stronger path of self-criticism to social maladjustment in the boys could be attributed to the social support they received from others. High levels of self-criticism mean limited relationships and social network as self-critical people have a more restricted social circle due to their pessimistic view of others. Although they have high levels of self-criticism, girls might experience lower social maladjustment compared to boys because they have better social relations and receive more social support from others.

The limitations of this research were the statistical population that was limited to high school students of Ahvaz, the limited ability of structural equations modeling in proving causality and the limitations related to the use of self-report questionnaires.

5. Conclusion

This study highlighted the importance of anger rumination, self-criticism and psychological flexibility in predicting social maladjustment in adolescents living in Ahvaz. Due to the negative impact of self-criticism on flexibility and adaptive behavior of students, it is recommended that they participate in workshops and courses on self-criticism. Increasing psychological flexibility and resilience in students may affect their social adjustment. Therefore, it is suggested that this variable be considered in the courses and workshops provided to them. Since, the knowledge and help of teachers, managers and parents can affect the efficiency of the courses, it is also suggested to provide them courses on the investigated variables. It is recommended that gender differences be considered when holding any of the mentioned workshops and training courses be designed and offered taking these differences into consideration.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The current study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Islamic Azad University Ahvaz Branch. Iran (code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1399.120)

Funding

This article was extracted from the PhD dissertation of the first author in the Department of Psychology, Ahvaz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran.

Authors' contributions

All authors have equally contributed in preparing the article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the individuals who participated in the research.

References

- Li L, Li S, Wang Y, Yi J, Yang Y, He J, Zhu X. Coping profiles differentiate psychological adjustment in Chinese women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Integr Cancer Ther. 2017; 16(2):196-204. [DOI:10.1177/1534735416646854] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Romera EM, Gómez-Ortiz O, Ortega-Ruiz R. The mediating role of psychological adjustment between peer victimization and social adjustment in adolescence. Front Psychol. 2016; 7:1749. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01749] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Piqueras JA, Mateu-Martínez O, Cejudo J, Pérez-González JC. Pathways into psychosocial adjustment in children: Modeling the effects of trait emotional intelligence, social-emotional problems, and gender. Front Psychol. 2019; 10:507. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00507] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Derosier ME, Lloyd SW. The impact of children’s social adjustment on academic outcomes. Read Writ Q. 2011; 27(1):25-47. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Karadag E. The effect of social adjustment on student achievement. In: Karadag E, editors. The factors effecting student achievement: Meta-analysis of empirical studies. New York: Springer; 2017. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-56083-0]

- Wei MH. The social adjustment, academic performance, and creativity of Taiwanese children with Tourette’s syndrome. Psychol Rep. 2011; 108(3):791-8. [DOI:10.2466/04.07.10.PR0.108.3.791-798] [PMID]

- Ibrahim K, Kalvin C, Marsh CL, Anzano A, Gorynova L, Cimino K, et al. Anger rumination is associated with restricted and repetitive behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019; 49(9):3656-68. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-019-04085-y] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Teymouri Z, Mojtabaei M, Rezazadeh SMR. The effectiveness of emotionally focused couple therapy on emotion regulation, anger rumination, and marital intimacy in women affected by spouse infidelity. Caspian J Health Res. 2020; 5(4):78-82. [DOI:10.52547/cjhr.5.4.78]

- de la Fuente-Anuncibay R, González-Barbadillo Á, Ortega-Sánchez D, Ordóñez-Camblor N, Pizarro-Ruiz JP. Anger Rumination and mindfulness: Mediating effects on forgiveness. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(5):2668. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18052668] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Peters JR, Smart LM, Eisenlohr-Moul TA, Geiger PJ, Smith GT, Baer RA. Anger rumination as a mediator of the relationship between mindfulness and aggression: The utility of a multidimensional mindfulness model. J Clin Psychol. 2015; 71(9):871-84. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.22189] [PMID]

- Kim JE, Park JH, Park SH. Anger suppression and rumination sequentially mediates the effect of emotional labor in Korean nurses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019; 16(5):799. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph16050799] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Gao F, Yao Y, Yao C, Xiong Y, Ma H, Liu H. The mediating role of resilience and self-esteem between negative life events and positive social adjustment among left-behind adolescents in China: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2019; 19(1):239. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-019-2219-z] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kopala-Sibley DC, Klein DN, Perlman G, Kotov R. Self-criticism and dependency in female adolescents: Prediction of first onsets and disentangling the relationships between personality, stressful life events, and internalizing psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol. 2017; 126(8):1029-43. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Schanche E. The transdiagnostic phenomenon of self-criticism. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2013; 50(3):316-21. [DOI:10.1037/a0032163] [PMID]

- Tyndall I, Waldeck D, Pancani L, Whelan R, Roche B, Pereira A. Profiles of psychological flexibility: A latent class analysis of the acceptance and commitment therapy model. Behav Modif. 2020; 44(3):365-93. [PMID]

- Hulbert-Williams NJ, Storey L. Psychological flexibility correlates with patient-reported outcomes independent of clinical or sociodemographic characteristics. Support Care Cancer. 2016; 24(6):2513-21. [PMID]

- Ruskin D, Campbell L, Stinson J, Ahola Kohut S. Changes in parent psychological flexibility after a one-time mindfulness-based intervention for parents of adolescents with persistent pain conditions. Children (Basel). 2018; 5(9):121. [DOI:10.3390/children5090121] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kashdan TB, Rottenberg J. Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010; 30(7):865-78. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Waldeck D, Pancani L, Holliman A, Karekla M, Tyndall I. Adaptability and psychological flexibility: Overlapping constructs? J Contextual Behav Sci. 2021; 19:72-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2021.01.002]

- Endendijk JJ, Groeneveld MG, Mesman J. The gendered family process model: An integrative framework of gender in the family. Arch Sex Behav. 2018; 47(4):877-904. [DOI:10.1007/s10508-018-1185-8] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sukhodolsky DG, Golub A, Cromwell EN. Development and validation of the anger rumination scale. Pers Individ Dif. 2001; 31(5):689-700. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00171-9]

- Mahmoudi T, BasakNejad S, Mehrabizadeh Honarmand M. [Psychometric characteristics of Anger Rumination Scale (ARS) in students (Persian)]. J Sabzevar Univ Med Sci. 2014; 21(3):453-62. http://jsums.medsab.ac.ir/article_447.html?lang=en

- Thompson R, Zuroff DC. The Levels of Self-Criticism Scale: Comparative self-criticism and internalized self-criticism. Pers Individ Dif. 2004; 36(2):419-30. [DOI:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00106-5]

- Basharpoor S, Khoshsorour S. [Psychometric properties of Persian version of the Multidimensional Self-Disgust Scale (MSDS) (Persian)]. Q J Soc Cogn. 2020; 9(2):59-78. http://sc.journals.pnu.ac.ir/article_7315.html?lang=en

- Abasi E, Fti L, Molodi R, Zarabi H. Psychometric properties of Persian version of acceptance and action questionnaire–II. Psychological Methods and Modles. 2013; 3(10):65-80. http://jpmm.miau.ac.ir/article_61.html?lang=en

- Wolgast M. What does the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II) really measure? Behav Ther. 2014; 45(6):831-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2014.07.002] [PMID]

- Rahdar M, Seydi MS, Rashidi A. [Path analysis of family leisure to social development by mediating the quality of Parent-Adolescent communication and the quality of Relationships with Peers (Persian)]. Q Soc Psychol Res. 2020; 10(37):29-44. https://www.socialpsychology.ir/article_109695.html?lang=en

- Eifert GH, Forsyth JP. The application of acceptance and commitment therapy to problem anger. Cogn Behav Pract. 2011;18(2):241-50. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.04.004]

- Besharat MA, Ramesh S, Nogh H. [The predicting role of worry, anger rumination and social loneliness in adjustment to coronary artery disease (Persian)]. Iran J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2018; 6(4):6-15. http://journal.icns.org.ir/article-1-485-fa.html

- Barzegari Dehej A, Jahandari P, Mahmoodpour A, Naderi R. [The mediating role of self-compassion in terms of rumination and depression symptoms in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (Persian)]. J Nurse Physician War. 2018; 6(19):32-40. http://npwjm.ajaums.ac.ir/article-1-554-fa.html

- Dajani DR, Uddin LQ. Demystifying cognitive flexibility: Implications for clinical and developmental neuroscience. Trends Neurosci. 2015; 38(9):571-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.tins.2015.07.003] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rajabi G, Abasi G. [Investigating the relationship between self-criticism, social anxiety and fear of failure with shyness in students (Persian)]. Res Clin Psychol Couns. 2012; 1(2):171-82. https://tpccp.um.ac.ir/article_29766.html

- Malekpour F, Mehrabizadeh M, Rahimi M. [The causal relationship of types of self-absorption and maladaptive perfectionism with depression through the mediating role of self-criticism in university students (Persian)]. Q J Psychol Stud. 2017; 13(3):25-42. https://psychstudies.alzahra.ac.ir/article_3030.html?lang=en

Article Type: Original Contributions |

Subject:

Health Education and Promotion

Received: 2021/07/20 | Accepted: 2021/11/10 | Published: 2022/01/1

Received: 2021/07/20 | Accepted: 2021/11/10 | Published: 2022/01/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |