Volume 7, Issue 3 (7-2022)

CJHR 2022, 7(3): 175-184 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Masoudi Rad N, Rabiei M, Samami M. The significance of coronavirus disease 2019 in dentistry: A scoping review. CJHR 2022; 7 (3) :175-184

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-257-en.html

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-257-en.html

1- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine, School of Dentistry, Pardis International Branch, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

2- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine, School of Dentistry, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- Dental Sciences Research Center, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine, School of Dentistry, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran , m_samami@alumnus.tums.ac.ir

2- Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine, School of Dentistry, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- Dental Sciences Research Center, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Medicine, School of Dentistry, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran , m_samami@alumnus.tums.ac.ir

Full-Text [PDF 878 kb]

(260 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (868 Views)

Full-Text: (330 Views)

1. Introduction

The first case of a specific type of pneumonia with an unknown cause was detected and reported in December 2019 in Wuhan city of Hubei Province in China. The cause was identified to be the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and the disease was named Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) [1, 2]. Soon after, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the COVID-19 pandemic situation [3, 4]. COVID-19 can affect people of all ages. However, old age, and presence of underlying systemic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular and respiratory diseases are significantly associated with a poorer prognosis and higher rates of morbidity and mortality [5]. The most important feasible strategy and practical approach to confront the disease transmission was found to be vaccination to induce immunity prior to affliction with the disease. Thus, the pharmaceutical companies worldwide put all their efforts to develop COVID-19 vaccine. However, the COVID-19 viral genome undergoes continuous mutations, and each new variant can target a new age group, shifting from the elderly to children. Also, the spreading ability and infectivity of the virus, and the associated morbidity and mortality rates can change with each mutation. People that are against vaccination can cause new disease peaks in different communities [6, 7].

The healthcare workers are at higher risk of COVID-19 infection. Dental clinicians are in close contact with patients in the process of conduction of dental procedures, and are exposed to the generated aerosols and saliva droplets. Thus, they are at high risk of infection with COVID-19 pandemic. The risk is also high for dental patients and the staff [8, 9].

To date, adherence to protective and preventive measures has been the most important strategies to confront COVID-19 [8, 10]. Since dentists are at high risk of COVID-19 infection and transmission, they are expected to have adequate knowledge about its routes of transmission, protection principles, and preventive strategies. This study aimed to conduct a scoping review on infection control in dentistry during the COVID-19 era. The main objective of this study was to find the most effective strategies for dental clinicians, the staff, and patients for prevention and control of COVID-19 before, during, and after dental procedures.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review focuses on infection control, routes of transmission, and prevention of COVID-19 in dental office setting. The review was carried out according to the five stages of conduct proposed by Arksey and O’Malley namely (I) specification of research goals and search strategy, (II) identifying the relevant literature, (III) study selection, (IV) data extraction, and (V) summarizing, synthesizing, analyzing, and reporting the results [11]. Table 1 presents the stages of this review in brief.

.jpg)

The latest findings available in most accredited databases and scientific websites including Science Direct, Scopus, PubMed, and Google Scholar, and the guidelines recommended by the World Health Organization, the United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention, American Dental Association, Iranian Dental Association, and the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education were searched by the titles and abstracts using the following MeSH terms: “COVID-19”, “Dentistry”, “Infection Control”, and “SARS-CoV-2”, (“SARS-CoV-2) AND (“Dentistry” OR “Dental” OR “COVID-19” OR “Corona” OR “Coronavirus” OR “COVID-19”) AND (“SARS-CoV-2). A search was conducted for English articles published from 2020.01.01 to 2022.01.01. Duplicates were removed, and irrelevant and invalid articles were excluded by reviewing the titles, abstracts, and full-texts of the articles. Comparison and assessment of the eligibility of the articles were performed by consensus among the researchers, and cases of disagreement were discussed with another researcher. Data extraction was performed independently by each researcher using predesigned forms, and the collected data were then compared and assessed in a panel of experts. The PRISMA flowchart was used to select the relevant articles according to the research question by the researchers with a teamwork approach. Table 1 presents the phases of this scoping review in detail.

3. Results

Of a total of 27,350 articles and 1200 other pieces of literature, 10,127 were deleted since they were duplicates, 18,193 were deleted due to absence of keywords, and 206 were deleted since they did not meet the study objectives. After screening, 24 eligible articles remained (Figure 1).

The first case of a specific type of pneumonia with an unknown cause was detected and reported in December 2019 in Wuhan city of Hubei Province in China. The cause was identified to be the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and the disease was named Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) [1, 2]. Soon after, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the COVID-19 pandemic situation [3, 4]. COVID-19 can affect people of all ages. However, old age, and presence of underlying systemic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular and respiratory diseases are significantly associated with a poorer prognosis and higher rates of morbidity and mortality [5]. The most important feasible strategy and practical approach to confront the disease transmission was found to be vaccination to induce immunity prior to affliction with the disease. Thus, the pharmaceutical companies worldwide put all their efforts to develop COVID-19 vaccine. However, the COVID-19 viral genome undergoes continuous mutations, and each new variant can target a new age group, shifting from the elderly to children. Also, the spreading ability and infectivity of the virus, and the associated morbidity and mortality rates can change with each mutation. People that are against vaccination can cause new disease peaks in different communities [6, 7].

The healthcare workers are at higher risk of COVID-19 infection. Dental clinicians are in close contact with patients in the process of conduction of dental procedures, and are exposed to the generated aerosols and saliva droplets. Thus, they are at high risk of infection with COVID-19 pandemic. The risk is also high for dental patients and the staff [8, 9].

To date, adherence to protective and preventive measures has been the most important strategies to confront COVID-19 [8, 10]. Since dentists are at high risk of COVID-19 infection and transmission, they are expected to have adequate knowledge about its routes of transmission, protection principles, and preventive strategies. This study aimed to conduct a scoping review on infection control in dentistry during the COVID-19 era. The main objective of this study was to find the most effective strategies for dental clinicians, the staff, and patients for prevention and control of COVID-19 before, during, and after dental procedures.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review focuses on infection control, routes of transmission, and prevention of COVID-19 in dental office setting. The review was carried out according to the five stages of conduct proposed by Arksey and O’Malley namely (I) specification of research goals and search strategy, (II) identifying the relevant literature, (III) study selection, (IV) data extraction, and (V) summarizing, synthesizing, analyzing, and reporting the results [11]. Table 1 presents the stages of this review in brief.

.jpg)

The latest findings available in most accredited databases and scientific websites including Science Direct, Scopus, PubMed, and Google Scholar, and the guidelines recommended by the World Health Organization, the United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention, American Dental Association, Iranian Dental Association, and the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education were searched by the titles and abstracts using the following MeSH terms: “COVID-19”, “Dentistry”, “Infection Control”, and “SARS-CoV-2”, (“SARS-CoV-2) AND (“Dentistry” OR “Dental” OR “COVID-19” OR “Corona” OR “Coronavirus” OR “COVID-19”) AND (“SARS-CoV-2). A search was conducted for English articles published from 2020.01.01 to 2022.01.01. Duplicates were removed, and irrelevant and invalid articles were excluded by reviewing the titles, abstracts, and full-texts of the articles. Comparison and assessment of the eligibility of the articles were performed by consensus among the researchers, and cases of disagreement were discussed with another researcher. Data extraction was performed independently by each researcher using predesigned forms, and the collected data were then compared and assessed in a panel of experts. The PRISMA flowchart was used to select the relevant articles according to the research question by the researchers with a teamwork approach. Table 1 presents the phases of this scoping review in detail.

3. Results

Of a total of 27,350 articles and 1200 other pieces of literature, 10,127 were deleted since they were duplicates, 18,193 were deleted due to absence of keywords, and 206 were deleted since they did not meet the study objectives. After screening, 24 eligible articles remained (Figure 1).

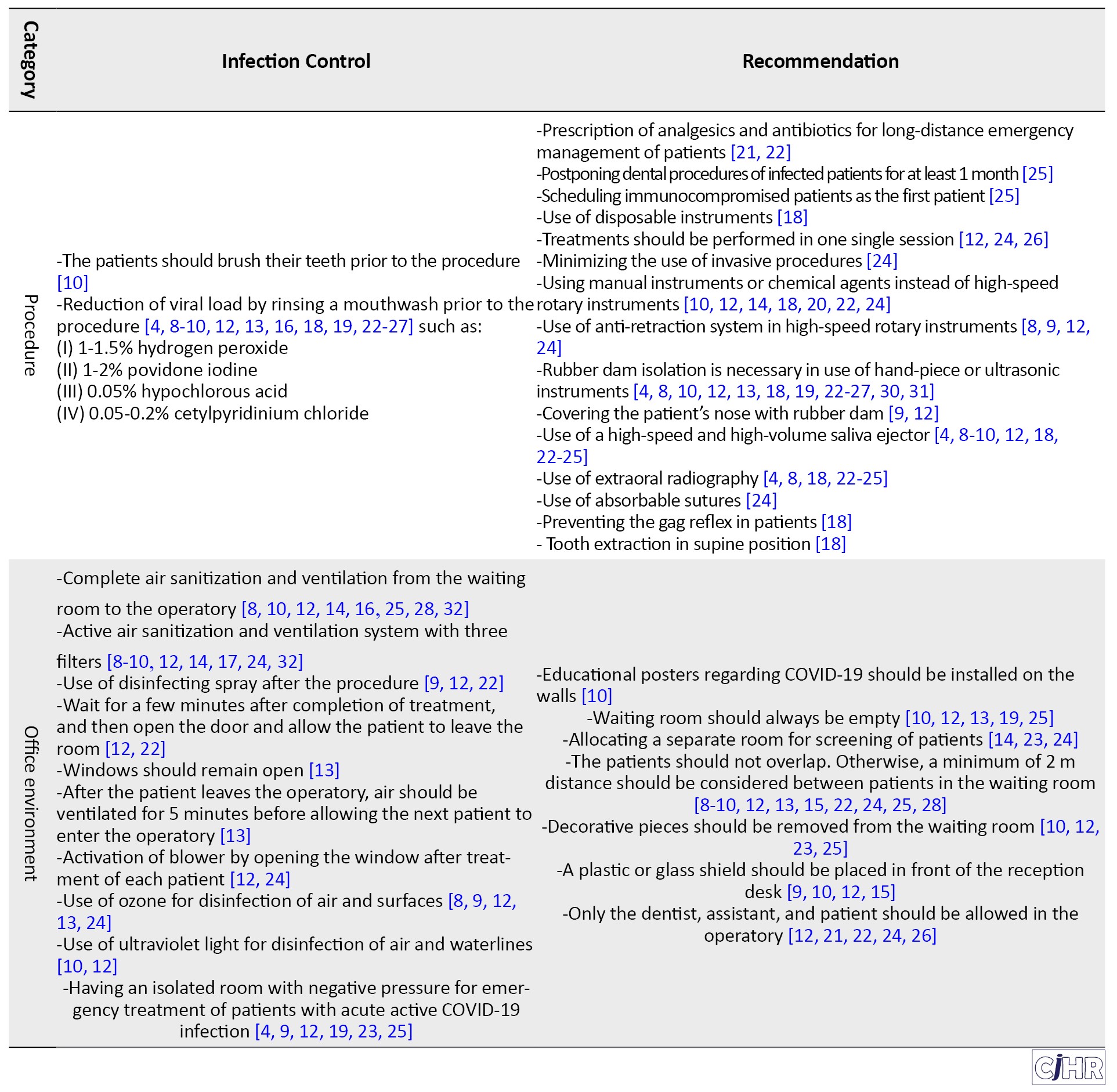

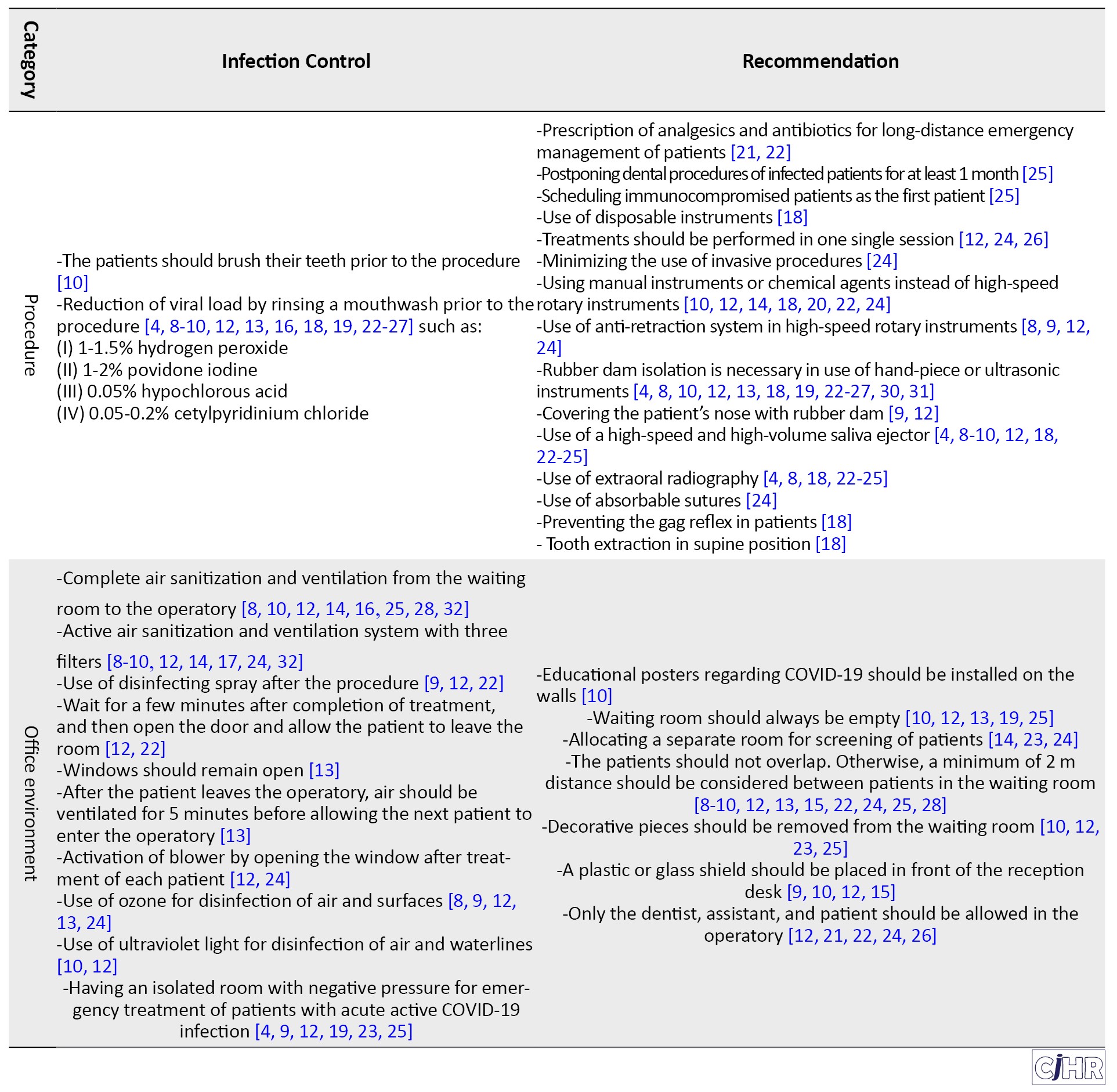

Table 2 presents the extracted data from the articles.

Of eligible articles, 13 articles only allowed emergency dental procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic, and recommended postponing other procedures [4, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22]. However, all of them emphasized on primary triage of patients prior to their admission, personal protective measures, optimal environmental safety measures, and use of equipment to control contaminants and aerosols. Fourteen articles suggested mouthwash rinse prior to dental procedures to decrease the viral load [4, 8, 12, 13, 16, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27]. Final recommendations are presented in Table 2.

4. Discussion

This study was designed aiming to empower the dental clinicians in provision of clinical dental services during the COVID-19 pandemic by their knowledge enhancement. The topics discussed in this review can help to resume dental profession during the pandemic and even after global vaccination and overcoming the COVID-19 pandemic. In this study, management of patients was discussed in three categories of prior to entering the office, in the office, and after leaving the office.

Prior to entering the office

Since prevention of infection transmission is the most important factor to consider in COVID-19 pandemic, primary triage of patients over the phone prior to treatment is among the main responsibilities of the staff [12, 18]. It is recommended to postpone dental procedures for a minimum of 30 days after COVID-19 infection. Also, all emergency dental procedures should be performed by complete adherence to the protective protocols [10, 20, 22]. The prioritized emergency treatments include pain control, management of jaw fractures with a risk of airway obstruction, bacterial infections of oral soft tissue with a risk of airway obstruction or involving the eyes, and uncontrolled postoperative bleeding. In such cases, patients should be referred to professional centers. For forensic purposes, all patient responses during over-the-phone and in-person triage should be recorded and verified by patients [4, 8, 9]. Patients should also receive the required instructions regarding adherence to office protocols such as wearing a mask, bringing their own pen, paying with debit card instead of cash, and not having any companions [10, 12, 15].

In the office

All patients should wear an appropriate mask when entering the office. Patients are required to step into a tray containing sodium hypochlorite (800 mL water plus 200 mL of sodium hypochlorite with 10,000 ppm, which should be replaced every 4 hours) or must wear disposable shoe covers. These instructions were particularly emphasized before global vaccination. Also, the patients should disinfect their hands with hand sanitizers available in the office. If the patient leaves the office for a while and then comes back, all the aforementioned steps should be repeated [24, 25]. A separate safe room should be preferably considered for active screening of patients to minimize contact between patients, the staff, and dental clinician. The medical history of patients should be reevaluated in the office as well. Also, measuring the body temperature of each patient is recommended during COVID-19 peaks. If the patient’s medical history suggests the possibility of infection or being a carrier, or if the patient’s body temperature is higher than 37.5°C (99.5°F), the patient should lockdown himself/herself at home for a minimum of 14 days or should go to a hospital [14, 15, 20, 22, 27].

During dental procedures

Reduction of viral load: It is recommended to use an antiseptic mouthwash to minimize the viral load in the oral cavity. Literature is controversial regarding the efficacy of chlorhexidine for this purpose since it has low virucidal effect on the coronavirus. Mouthwashes have low substantivity on the oral mucosa, and the viruses present in the saliva can easily re-colonize the mucosa; 1% hydrogen peroxide is most commonly recommended for this purpose due to its optimal virucidal effect. To prepare 15 mL of 1% hydrogen peroxide, 5 mL of 3% hydrogen peroxide should be added to 10 mL of distilled water [13, 16, 18, 19, 24, 26].

Use of rubber dam: Use of rubber dam is recommended during the use of hand-piece or ultrasonic instruments in emergency cases; however, it would complicate the conduction of some dental procedures. It has been reported that if correctly placed, rubber dam can decrease the spread of infected saliva droplets and aerosols by 70% around the clinician, and can significantly decrease the risk of cross-contamination. If a rubber dam cannot be used, conservative use of manual instruments instead of rotary devices is recommended [18, 22, 24, 27].

Saliva ejector: Using a high-speed and high-volume saliva ejector or surgical suction can significantly decrease the spread of saliva droplets [4, 8, 9, 23, 25].

High-speed rotary instruments: If manual instruments cannot be used for treatment, high-speed rotary instruments equipped with anti-retraction systems should be used to decrease the spread of debris and infected droplets, and patients requiring such procedures should be scheduled as the last patient of the day [8, 9].

Air sanitation in the office: Aerosols contain living viruses; however, their infectivity progressively decreases within 3 hours, and the viruses have a mean half-life of approximately 1.1 hours. Thus, sanitation of office air from the waiting room to the operatory is of utmost importance. In treatment of each patient, a ventilation system with three filters should be turned on to clean the air in the operatory and remove the impurities and particles measuring 0.01 µm in size [14, 16, 17, 28, 32]. After completion of each procedure, a disinfecting spray should be used in the operatory, and the door should be opened after 2 minutes. In-between patients, the operatory should remain empty for a couple of minutes, the windows should be opened, and the blower should be turned on to create a safe environment for the next patient [12, 13, 22, 24]. Ozone gas may be used as a highly effective agent for disinfection of air and surfaces. Also, ultraviolet light can be used to disinfect the air and waterlines since it can decrease viral proliferation and infectivity. Emergency treatments for a COVID-19 positive patient should be performed in an isolated or negative-pressure room [9, 10, 12, 24].

Disinfection of office environment

It has been shown that the SARS-Cov2 can remain viable on plastic, glass, and metal surfaces for a maximum of 9 days. Active viability of the virus is 72 hours on plastic surfaces, 48 hours on stainless steel surfaces, 24 hours on cardboards, and 4 hours on copper surfaces. Thus, all surfaces in a dental office (in the waiting room and the operatory) should be considered potentially infected, and must be regularly and carefully disinfected with disinfecting agents after treatment of each patient. The optimal disinfecting agents for this purpose include 62%-71% ethanol, 0.5% hydrogen peroxide, 0.1% sodium hypochlorite, and isopropyl alcohol (propanol). Some authors have recommended covering all surfaces in a dental office with polyethylene wraps [9, 13, 30]. The World Health Organization recommends using 5% sodium hypochlorite diluted 1:100 for 10 minutes for surface disinfection [10, 12, 28]. Dental clinicians should wash hands with soap carefully for a minimum of 20 seconds before and after each patient. The surfactant of soap can dissolve the lipid membrane of the virus, and cause viral lysis. It has been recommended to use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer (with alcohol concentration over 60% or 70%) after handwashing with soap to cleave the viral residues [15, 26, 30]. Such protective measures should be followed even in the post-pandemic era.

Personal protection

Use of personal protective equipment should be strictly followed in the office. These include a head cover, water-resistant disposable surgical gown, gloves, goggles, face shield, and disposable shoe covers. Such equipment should be used correctly to prevent their contamination. Also, their safe disposable is highly important. The most important measure to prevent infection transmission is to use an optimal face mask, which is of utmost importance due to aerosol-generating nature of most dental procedures [12, 16, 22, 23].

Airway protection: Surgical masks were commonly used in dental offices prior to COVID-19 pandemic which were suitable to prevent the spread of infective blood and saliva particles. However, masks with a pore size < 50 µm should be necessarily worn for protection against COVID-19 [12, 23]. Dental clinicians and the staff should wear a face mask during their entire presence in the office. Different masks are available based on their rate of filtration of particles. During aerosol-generating dental procedures, FFP2/N95, FFP3/N99, and N100 have the highest efficacy because the COVID-19 viral particles present in air droplets have a diameter between 0.06 to 0.14 nm. Thus, both dental clinician and assistant should wear such masks [10, 14, 16, 30]. These masks can be used for a maximum of 4 hours, and then should be replaced. If the mask has a suitable condition, it may be sterilized for up to 3 times using hydrogen peroxide vapor, dry heat (70°C for 30 minutes) or moist heat (121°C) [8, 12, 13, 31]. Surgical masks can be used for non-aerosol-generating procedures or by other active staff members that are not in direct contact with patient. However, optimal fit of the mask should be ensured. Face masks without an exhalation valve provide mutual protection for both dental clinician and patient, and are preferred. If a face mask with valve is used, additional coverage with a surgical mask should be considered [12, 24].

Eye protection: Due to the possibility of virus transmission through the conjunctiva, eye protection with goggles and face shield should be considered [14, 16, 21].

Recommendations for specific fields of dentistry

Radiology: Radiographs with minimum risk of stimulation of gag reflex and coughing such as panoramic radiography, cone-beam computed tomography, and lateral oblique radiography should be requested instead of intraoral periapical and bitewing radiographs for diagnostic purposes. However, the indications and cost of these radiographic modalities should be considered as well. If intraoral radiography is necessarily required, the sensors should be double-covered for higher protection. Also, the radiology clinic should preferably email the radiographs or send them electronically instead of handing them over to patients [4, 9, 22, 25].

Endodontics and restorative dentistry: According to the American Dental Association, caries should be preferably removed with less invasive modalities such as chemomechanical methods and use of hand instruments instead of rotary devices. If possible, in cases with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis, pain reduction with pulpotomy, pulpectomy, or vital pulp therapy should be preferred over routine root canal therapy [22, 25]. If such treatments cannot be performed, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as 600 mg ibuprofen plus 500 mg paracetamol should be prescribed for symptomatic irreversible pulpitis, symptomatic apical periodontitis, and acute apical abscess. In case of acute infection, beta-lactam antibiotics must be temporarily prescribed. The patient should then present to well-equipped centers for treatment to eliminate the need for repeated antibiotic therapy [9, 12, 25].

Periodontics: Scaling and polishing with manual instruments should be preferred to ultrasonic devices [12, 25]. However, it is hoped that ultrasonic instruments can be used again for vaccinated patients after global vaccination and optimal control of COVID-19 pandemic. It should be noted that air ventilation is the first priority in use of ultrasonic instruments.

Oral surgery: In case of tooth extraction, high-speed saliva ejector should be used especially if the patient is in supine position. Use of absorbable sutures is also recommended. For patients with severe pain due to a severely carious tooth, extraction should be preferred to restorative procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic [25].

Prosthodontics: For recementation of loose prosthetic crowns, the patients are recommended to use an over-the-counter temporary cement, and cement their crown at home instead of presenting to a dental office. In case of misfit of a removable denture, the patients can temporarily use over-the-counter soft liners to temporarily preserve esthetics and function [25]. For disinfection of dental impressions, 1% sodium hypochlorite has been recommended (10 minutes for alginate, and 15-20 minutes for elastomeric impressions) [12].

Pediatric dentistry: Only one adult is allowed to accompany a pediatric patient, who should not be allowed in the operatory [12].

Orthodontics: All non-emergency orthodontic treatments should be postponed. Dental clinicians should not activate rapid palatal expanders during the COVID-19 pandemic peaks. Also, the parents should be instructed on how to adjust a NiTi archwire in case of emergency to prevent traumatic mucosal ulcers [12].

What would be the future of dental profession considering the ongoing global vaccination programs? Considering the repeated mutations of the virus, can dental clinicians resume their professional life? The main priority of this study was to show the feasibility of provision of dental services during the COVID-19 pandemic and also in the post-pandemic era. The patients may be asked to show their QR or vaccination link. In that case, dental clinicians and the staff would provide dental care services to patients with a more positive attitude. However, it is noteworthy that infection control has always been an inseparable part of dental profession, and face mask, gloves, and disinfection of surfaces were and always will be mandatory.

5. Conclusion

This scoping review focused on different routes of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a dental office setting, and offered infection control strategies in three categories: prior to entering the office, during a dental visit, and after that, in the COVID-19 pandemic era. Considering the high risk of virus transmission in dental office setting, dentists should precisely follow the protocols, and patients should be well instructed to adhere to the protocols prior to their visit to ensure safe provision of services. Considering the repeated mutations of the virus and its increasing transmissibility, poor adherence of some people to protective measures after vaccination, and publication of some inaccurate papers during the pandemic, further more precise studies are required to focus on recent variants of SARS-CoV-2.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was part of a project with the ethics code conducted at Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Iran (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1400.255).

Funding

This study was funded by the National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education, Tehran, Iran (Grant No. 991408).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and Supervision: Maryam Rabiei; Methodology: Maryam Rabiei; Investigation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review & editing, Data collection, Data analysis, and final approval of the study: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ideh Dadgaran and Dr. maryam shakiba for their insightful comments that assisted improve the manuscript.

References

Of eligible articles, 13 articles only allowed emergency dental procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic, and recommended postponing other procedures [4, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22]. However, all of them emphasized on primary triage of patients prior to their admission, personal protective measures, optimal environmental safety measures, and use of equipment to control contaminants and aerosols. Fourteen articles suggested mouthwash rinse prior to dental procedures to decrease the viral load [4, 8, 12, 13, 16, 18, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27]. Final recommendations are presented in Table 2.

4. Discussion

This study was designed aiming to empower the dental clinicians in provision of clinical dental services during the COVID-19 pandemic by their knowledge enhancement. The topics discussed in this review can help to resume dental profession during the pandemic and even after global vaccination and overcoming the COVID-19 pandemic. In this study, management of patients was discussed in three categories of prior to entering the office, in the office, and after leaving the office.

Prior to entering the office

Since prevention of infection transmission is the most important factor to consider in COVID-19 pandemic, primary triage of patients over the phone prior to treatment is among the main responsibilities of the staff [12, 18]. It is recommended to postpone dental procedures for a minimum of 30 days after COVID-19 infection. Also, all emergency dental procedures should be performed by complete adherence to the protective protocols [10, 20, 22]. The prioritized emergency treatments include pain control, management of jaw fractures with a risk of airway obstruction, bacterial infections of oral soft tissue with a risk of airway obstruction or involving the eyes, and uncontrolled postoperative bleeding. In such cases, patients should be referred to professional centers. For forensic purposes, all patient responses during over-the-phone and in-person triage should be recorded and verified by patients [4, 8, 9]. Patients should also receive the required instructions regarding adherence to office protocols such as wearing a mask, bringing their own pen, paying with debit card instead of cash, and not having any companions [10, 12, 15].

In the office

All patients should wear an appropriate mask when entering the office. Patients are required to step into a tray containing sodium hypochlorite (800 mL water plus 200 mL of sodium hypochlorite with 10,000 ppm, which should be replaced every 4 hours) or must wear disposable shoe covers. These instructions were particularly emphasized before global vaccination. Also, the patients should disinfect their hands with hand sanitizers available in the office. If the patient leaves the office for a while and then comes back, all the aforementioned steps should be repeated [24, 25]. A separate safe room should be preferably considered for active screening of patients to minimize contact between patients, the staff, and dental clinician. The medical history of patients should be reevaluated in the office as well. Also, measuring the body temperature of each patient is recommended during COVID-19 peaks. If the patient’s medical history suggests the possibility of infection or being a carrier, or if the patient’s body temperature is higher than 37.5°C (99.5°F), the patient should lockdown himself/herself at home for a minimum of 14 days or should go to a hospital [14, 15, 20, 22, 27].

During dental procedures

Reduction of viral load: It is recommended to use an antiseptic mouthwash to minimize the viral load in the oral cavity. Literature is controversial regarding the efficacy of chlorhexidine for this purpose since it has low virucidal effect on the coronavirus. Mouthwashes have low substantivity on the oral mucosa, and the viruses present in the saliva can easily re-colonize the mucosa; 1% hydrogen peroxide is most commonly recommended for this purpose due to its optimal virucidal effect. To prepare 15 mL of 1% hydrogen peroxide, 5 mL of 3% hydrogen peroxide should be added to 10 mL of distilled water [13, 16, 18, 19, 24, 26].

Use of rubber dam: Use of rubber dam is recommended during the use of hand-piece or ultrasonic instruments in emergency cases; however, it would complicate the conduction of some dental procedures. It has been reported that if correctly placed, rubber dam can decrease the spread of infected saliva droplets and aerosols by 70% around the clinician, and can significantly decrease the risk of cross-contamination. If a rubber dam cannot be used, conservative use of manual instruments instead of rotary devices is recommended [18, 22, 24, 27].

Saliva ejector: Using a high-speed and high-volume saliva ejector or surgical suction can significantly decrease the spread of saliva droplets [4, 8, 9, 23, 25].

High-speed rotary instruments: If manual instruments cannot be used for treatment, high-speed rotary instruments equipped with anti-retraction systems should be used to decrease the spread of debris and infected droplets, and patients requiring such procedures should be scheduled as the last patient of the day [8, 9].

Air sanitation in the office: Aerosols contain living viruses; however, their infectivity progressively decreases within 3 hours, and the viruses have a mean half-life of approximately 1.1 hours. Thus, sanitation of office air from the waiting room to the operatory is of utmost importance. In treatment of each patient, a ventilation system with three filters should be turned on to clean the air in the operatory and remove the impurities and particles measuring 0.01 µm in size [14, 16, 17, 28, 32]. After completion of each procedure, a disinfecting spray should be used in the operatory, and the door should be opened after 2 minutes. In-between patients, the operatory should remain empty for a couple of minutes, the windows should be opened, and the blower should be turned on to create a safe environment for the next patient [12, 13, 22, 24]. Ozone gas may be used as a highly effective agent for disinfection of air and surfaces. Also, ultraviolet light can be used to disinfect the air and waterlines since it can decrease viral proliferation and infectivity. Emergency treatments for a COVID-19 positive patient should be performed in an isolated or negative-pressure room [9, 10, 12, 24].

Disinfection of office environment

It has been shown that the SARS-Cov2 can remain viable on plastic, glass, and metal surfaces for a maximum of 9 days. Active viability of the virus is 72 hours on plastic surfaces, 48 hours on stainless steel surfaces, 24 hours on cardboards, and 4 hours on copper surfaces. Thus, all surfaces in a dental office (in the waiting room and the operatory) should be considered potentially infected, and must be regularly and carefully disinfected with disinfecting agents after treatment of each patient. The optimal disinfecting agents for this purpose include 62%-71% ethanol, 0.5% hydrogen peroxide, 0.1% sodium hypochlorite, and isopropyl alcohol (propanol). Some authors have recommended covering all surfaces in a dental office with polyethylene wraps [9, 13, 30]. The World Health Organization recommends using 5% sodium hypochlorite diluted 1:100 for 10 minutes for surface disinfection [10, 12, 28]. Dental clinicians should wash hands with soap carefully for a minimum of 20 seconds before and after each patient. The surfactant of soap can dissolve the lipid membrane of the virus, and cause viral lysis. It has been recommended to use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer (with alcohol concentration over 60% or 70%) after handwashing with soap to cleave the viral residues [15, 26, 30]. Such protective measures should be followed even in the post-pandemic era.

Personal protection

Use of personal protective equipment should be strictly followed in the office. These include a head cover, water-resistant disposable surgical gown, gloves, goggles, face shield, and disposable shoe covers. Such equipment should be used correctly to prevent their contamination. Also, their safe disposable is highly important. The most important measure to prevent infection transmission is to use an optimal face mask, which is of utmost importance due to aerosol-generating nature of most dental procedures [12, 16, 22, 23].

Airway protection: Surgical masks were commonly used in dental offices prior to COVID-19 pandemic which were suitable to prevent the spread of infective blood and saliva particles. However, masks with a pore size < 50 µm should be necessarily worn for protection against COVID-19 [12, 23]. Dental clinicians and the staff should wear a face mask during their entire presence in the office. Different masks are available based on their rate of filtration of particles. During aerosol-generating dental procedures, FFP2/N95, FFP3/N99, and N100 have the highest efficacy because the COVID-19 viral particles present in air droplets have a diameter between 0.06 to 0.14 nm. Thus, both dental clinician and assistant should wear such masks [10, 14, 16, 30]. These masks can be used for a maximum of 4 hours, and then should be replaced. If the mask has a suitable condition, it may be sterilized for up to 3 times using hydrogen peroxide vapor, dry heat (70°C for 30 minutes) or moist heat (121°C) [8, 12, 13, 31]. Surgical masks can be used for non-aerosol-generating procedures or by other active staff members that are not in direct contact with patient. However, optimal fit of the mask should be ensured. Face masks without an exhalation valve provide mutual protection for both dental clinician and patient, and are preferred. If a face mask with valve is used, additional coverage with a surgical mask should be considered [12, 24].

Eye protection: Due to the possibility of virus transmission through the conjunctiva, eye protection with goggles and face shield should be considered [14, 16, 21].

Recommendations for specific fields of dentistry

Radiology: Radiographs with minimum risk of stimulation of gag reflex and coughing such as panoramic radiography, cone-beam computed tomography, and lateral oblique radiography should be requested instead of intraoral periapical and bitewing radiographs for diagnostic purposes. However, the indications and cost of these radiographic modalities should be considered as well. If intraoral radiography is necessarily required, the sensors should be double-covered for higher protection. Also, the radiology clinic should preferably email the radiographs or send them electronically instead of handing them over to patients [4, 9, 22, 25].

Endodontics and restorative dentistry: According to the American Dental Association, caries should be preferably removed with less invasive modalities such as chemomechanical methods and use of hand instruments instead of rotary devices. If possible, in cases with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis, pain reduction with pulpotomy, pulpectomy, or vital pulp therapy should be preferred over routine root canal therapy [22, 25]. If such treatments cannot be performed, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as 600 mg ibuprofen plus 500 mg paracetamol should be prescribed for symptomatic irreversible pulpitis, symptomatic apical periodontitis, and acute apical abscess. In case of acute infection, beta-lactam antibiotics must be temporarily prescribed. The patient should then present to well-equipped centers for treatment to eliminate the need for repeated antibiotic therapy [9, 12, 25].

Periodontics: Scaling and polishing with manual instruments should be preferred to ultrasonic devices [12, 25]. However, it is hoped that ultrasonic instruments can be used again for vaccinated patients after global vaccination and optimal control of COVID-19 pandemic. It should be noted that air ventilation is the first priority in use of ultrasonic instruments.

Oral surgery: In case of tooth extraction, high-speed saliva ejector should be used especially if the patient is in supine position. Use of absorbable sutures is also recommended. For patients with severe pain due to a severely carious tooth, extraction should be preferred to restorative procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic [25].

Prosthodontics: For recementation of loose prosthetic crowns, the patients are recommended to use an over-the-counter temporary cement, and cement their crown at home instead of presenting to a dental office. In case of misfit of a removable denture, the patients can temporarily use over-the-counter soft liners to temporarily preserve esthetics and function [25]. For disinfection of dental impressions, 1% sodium hypochlorite has been recommended (10 minutes for alginate, and 15-20 minutes for elastomeric impressions) [12].

Pediatric dentistry: Only one adult is allowed to accompany a pediatric patient, who should not be allowed in the operatory [12].

Orthodontics: All non-emergency orthodontic treatments should be postponed. Dental clinicians should not activate rapid palatal expanders during the COVID-19 pandemic peaks. Also, the parents should be instructed on how to adjust a NiTi archwire in case of emergency to prevent traumatic mucosal ulcers [12].

What would be the future of dental profession considering the ongoing global vaccination programs? Considering the repeated mutations of the virus, can dental clinicians resume their professional life? The main priority of this study was to show the feasibility of provision of dental services during the COVID-19 pandemic and also in the post-pandemic era. The patients may be asked to show their QR or vaccination link. In that case, dental clinicians and the staff would provide dental care services to patients with a more positive attitude. However, it is noteworthy that infection control has always been an inseparable part of dental profession, and face mask, gloves, and disinfection of surfaces were and always will be mandatory.

5. Conclusion

This scoping review focused on different routes of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in a dental office setting, and offered infection control strategies in three categories: prior to entering the office, during a dental visit, and after that, in the COVID-19 pandemic era. Considering the high risk of virus transmission in dental office setting, dentists should precisely follow the protocols, and patients should be well instructed to adhere to the protocols prior to their visit to ensure safe provision of services. Considering the repeated mutations of the virus and its increasing transmissibility, poor adherence of some people to protective measures after vaccination, and publication of some inaccurate papers during the pandemic, further more precise studies are required to focus on recent variants of SARS-CoV-2.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was part of a project with the ethics code conducted at Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Iran (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1400.255).

Funding

This study was funded by the National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education, Tehran, Iran (Grant No. 991408).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and Supervision: Maryam Rabiei; Methodology: Maryam Rabiei; Investigation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review & editing, Data collection, Data analysis, and final approval of the study: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ideh Dadgaran and Dr. maryam shakiba for their insightful comments that assisted improve the manuscript.

References

- Lee SA. Coronavirus Anxiety Scale: A brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Stud. 2020; 44(7):393-401. [DOI:10.1080/07481187.2020.1748481] [PMID]

- Watkins J. Preventing a covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020; 368:m810. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.m810] [PMID]

- Lu L, Xiong W, Liu D, Liu J, Yang D, Li N, et al. New onset acute symptomatic seizure and risk factors in coronavirus disease 2019: A retrospective multicenter study. Epilepsia. 2020; 61(6):e49-53. [DOI:10.1111/epi.16524] [PMCID]

- Meng L, Hua F, Bian Z. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Emerging and future challenges for dental and oral medicine. J Dent Res. 2020; 99(5):481-7. [DOI:10.1177/0022034520914246] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Asrani P, Eapen MS, Chia C, Haug G, Weber HC, Hassan MI, et al. Diagnostic approaches in COVID-19: Clinical updates. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2021; 15(2):197-212. [DOI:10.1080/17476348.2021.1823833] [PMID]

- Hebbani AV, Pulakuntla S, Pannuru P, Aramgam S, Badri KR, Reddy VD. COVID-19: Comprehensive review on mutations and current vaccines. Arch Microbiol. 2022; 204(1):8. [DOI:10.1007/s00203-021-02606-x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zawbaa HM, Osama H, El-Gendy A, Saeed H, Harb HS, Madney YM, et al. Effect of mutation and vaccination on spread, severity, and mortality of COVID-19 disease. J Med Virol. 2022; 94(1):197-204. [DOI:10.1002/jmv.27293] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Checchi V, Bellini P, Bencivenni D, Consolo U. COVID-19 dentistry-related aspects: a literature overview. Int Dent J. 2021; 71(1):21-6. [DOI:10.1111/idj.12601] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Amante LFLS, Afonso JTM, Skrupskelyte G. Dentistry and the COVID-19 outbreak. Int Dent J. 2021; 71(5):358-68. [DOI:10.1016/j.identj.2020.12.010] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Patel M. Infection control in dentistry during COVID-19 pandemic: what has changed? Heliyon. 2020; 6(10):e05402. [DOI:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05402] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005; 8(1):19-32. [DOI:10.1080/1364557032000119616]

- Villani FA, Aiuto R, Paglia L, Re D. COVID-19 and dentistry: prevention in dental practice, a literature review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020; 17(12):4609. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17124609] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Izzetti R, Nisi M, Gabriele M, Graziani F. COVID-19 transmission in dental practice: brief review of preventive measures in Italy. J Dent Res. 2020; 99(9):1030-8. [DOI:10.1177/0022034520920580] [PMID]

- Benzian H, Niederman R. A dental response to the COVID-19 pandemic-safer aerosol-free emergent (SAFER) Dentistry. Front Med (Lausanne). 2020; 7:520. [DOI:10.20944/preprints202005.0104.v1]

- Derruau S, Bouchet J, Nassif A, Baudet A, Yasukawa K, Lorimier S, et al. COVID-19 and dentistry in 72 questions: an overview of the literature. J Clin Med. 2021; 10(4):779. [DOI:10.3390/jcm10040779] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zimmermann M, Nkenke E. Approaches to the management of patients in oral and maxillofacial surgery during COVID-19 pandemic. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2020; 48(5):521-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcms.2020.03.011] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Panesar K, Dodson T, Lynch J, Bryson-Cahn C, Chew L, Dillon J. Evolution of COVID-19 guidelines for University of Washington oral and maxillofacial surgery patient care. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020; 78(7):1136-46. [DOI:10.1016/j.joms.2020.04.034] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fini MB. What dentists need to know about COVID-19. Oral oncol. 2020; 105:104741. [DOI:10.1016/j.oraloncology.2020.104741] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Jamal M, Shah M, Almarzooqi SH, Aber H, Khawaja S, El Abed R, et al. Overview of transnational recommendations for COVID-19 transmission control in dental care settings. Oral dis. 2021; 27(S 3):655-64. [DOI:10.1111/odi.13431] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Turkistani KA. Precautions and recommendations for orthodontic settings during the COVID-19 outbreak: A review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020; 158(2):175-81. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajodo.2020.04.016] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Volgenant CM, Persoon IF, de Ruijter RA, de Soet J. Infection control in dental health care during and after the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. Oral Dis. 2021; 27(S 3):674-83. [DOI:10.1111/odi.13408] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Siles-Garcia AA, Alzamora-Cepeda AG, Atoche-Socola KJ, Peña-Soto C, Arriola-Guillén LE. Biosafety for dental patients during dentistry care after COVID-19: A review of the literature. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2021; 15(3):e43-8. [DOI:10.1017/dmp.2020.252] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Wu KY, Wu DT, Nguyen TT, Tran SD. COVID-19’s impact on private practice and academic dentistry in North America. Oral dis. 2021; 27(S 3):684-7. [DOI:10.1111/odi.13444] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lucaciu O, Tarczali D, Petrescu N. Oral healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dent Sci. 2020; 15(4):399-402. [DOI:10.1016/j.jds.2020.04.012] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Banakar M, Bagheri Lankarani K, Jafarpour D, Moayedi S, Banakar MH, Mohammad Sadeghi A. COVID-19 transmission risk and protective protocols in dentistry: a systematic review. BMC Oral Health. 2020; 20(1):1-12. [DOI:10.1186/s12903-020-01270-9] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Vergara-Buenaventura A, Castro-Ruiz C. Use of mouthwashes against COVID-19 in dentistry. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2020; 58(8):924-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.08.016] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Samaranayake LP, Fakhruddin KS, Buranawat B, Panduwawala C. The efficacy of bio-aerosol reducing procedures used in dentistry: a systematic review. Acta Odontol Scand. 2021; 79(1):69-80. [DOI:10.1080/00016357.2020.1839673] [PMID]

- WHO. Infection prevention and control during health care when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected Interim guidance, 19 March 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665-331495

- WHO. Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Interim guidance, 27 February 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331215

- Peng X, Xu X, Li Y, Cheng L, Zhou X, Ren B. Transmission routes of 2019-nCoV and controls in dental practice. Int J Oral Sci. 2020; 12(1):9. [DOI:10.1038/s41368-020-0075-9] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, Solo K, Yaacoub S, Schünemann HJ, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. lancet. 2020; 395(10242):1973-87. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9]

- Tysiąc-Miśta M, Dubiel A, Brzoza K, Burek M, Pałkiewicz K. Air disinfection procedures in the dental office during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Pr. 2021; 72(1):39-48. [DOI:10.13075/mp.5893.01005]

Article Type: Narrative Review |

Subject:

Occupational Health

Received: 2021/12/19 | Accepted: 2022/05/27 | Published: 2022/07/1

Received: 2021/12/19 | Accepted: 2022/05/27 | Published: 2022/07/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |

.jpg)