Volume 9, Issue 1 (1-2024)

CJHR 2024, 9(1): 33-42 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1395.9221199206

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ashghali Farahani M, Zareian A, Khoshbakht-Pishkhani M, Khoshtrash M. Rejection, Current Suffering in the Lives of People with HIV/AIDS: A Qualitative Study in Iran. CJHR 2024; 9 (1) :33-42

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-352-en.html

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-352-en.html

Mansoureh Ashghali Farahani1

, Armin Zareian2

, Armin Zareian2

, Maryam Khoshbakht-Pishkhani3

, Maryam Khoshbakht-Pishkhani3

, Mehrnoosh Khoshtrash *

, Mehrnoosh Khoshtrash *

4

4

, Armin Zareian2

, Armin Zareian2

, Maryam Khoshbakht-Pishkhani3

, Maryam Khoshbakht-Pishkhani3

, Mehrnoosh Khoshtrash *

, Mehrnoosh Khoshtrash *

4

4

1- School of Nursing and Midwifery, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Health in Disaster & Emergencies, Nursing Faculty, Aja University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Medical-Surgical Nursing Department, Shahid Beheshti School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences,Rasht,Iran

4- Nursing Department, Shahid Beheshti School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran , mehrnoosh_kh72@yahoo.com

2- Department of Health in Disaster & Emergencies, Nursing Faculty, Aja University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Medical-Surgical Nursing Department, Shahid Beheshti School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences,Rasht,Iran

4- Nursing Department, Shahid Beheshti School of Nursing and Midwifery, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran , mehrnoosh_kh72@yahoo.com

Full-Text [PDF 506 kb]

(61 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (181 Views)

Full-Text: (62 Views)

Introduction

More than forty years have passed since the first reports on acquired immune deficiency virus (HIV). However, HIV infection remains a major global health problem [1]. HIV is an obstacle to the development of society and involves most of its active and productive population [2]. The importance of the disease can be visualized by the spread of an epidemic in 84.2 million people and 40.1 million deaths. In 2021, 1.5 million individuals worldwide contracted HIV, with six million living in Asia and Oceania [3]. Iran is also one of the most dangerous countries for HIV infection. Changes in the value system and social and economic structure in Iran have paved the way for new patterns of sexual behavior among Iranian youth [4]. Approximately 4100 new infections occur annually in Iran, and 2500 people die of this disease [5].

HIV/AIDS has affected patients’ physical, mental, and social health by creating various social problems, misconceptions in society, and social stigma [6]. Apart from living with a potentially life-threatening and chronic disease, people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) encounter numerous challenges, including the effect of the disease on their personal relationships with friends, family, colleagues, and healthcare providers [7]. Living with HIV/AIDS results in serious pressures on personal relationships, often leading to rejection and termination of relationships [8]. HIV Stigma affects the entire PLWHA family [9]. PLWHA’s social interactions with family members can become complicated, which often causes communication problems in the family [8]. HIV/AIDS also increases social isolation and rejection, avoidance by friends [8, 9], and separation by colleagues [8, 10]and worsens relationships with health professionals [11].

The impact of HIV/AIDS on social relations and support can have severe consequences for health condition of PLWHA. The importance of social support for HIV/AIDS has been widely documented. In general, strong social support is associated with slower disease progression, higher immune system performance [12, 13], and better adherence to treatment [14, 15, 16]. PLWHA, with strong social support networks, may employ more active coping strategies [17, 18] and enjoy better psychological well-being and mental health [19, 20]. The negative effect of HIV/AIDS stigma appears to be fading among people with strong social support networks [21]. Social support also plays a major role in improving HIV-positive individuals’ quality of life [22, 23, 24]. Although various quantitative and qualitative studies have studied the impact of PLWHA social relationships on their physical and mental health, and a number of qualitative studies have also examined aspects of PLWHA interpersonal relationships, there was no qualitative study that specifically and comprehensively examined PLWHA interpersonal relationships, especially in Iran, where family and social relationships are of particular importance. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the challenges faced by PLWHA in their daily social interactions.

Materials and Methods

The purpose of this qualitative content analysis was to determine the challenges of PLWHA in their daily social interactions. Data were collected from 12 PLWHA referring to the Behavioral Disease Counseling Center of Imam Khomeini Hospital, in Tehran and Behavioral Disease Counseling Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences in Rash City from April to September 2018. Purposive sampling and maximum variation were used to select participants. The inclusion criteria included speaking Persian and willingness to participate in the study. The first participant was selected based on her willingness to talk with the researcher. Semi-structured, face-to-face, recorded interviews were used for data collection. The research team designed an open-ended interview guide with the following questions: What social activities do you participate in? What is your relationship with others? Would you like to tell others about your disease? Questions and comments were followed up with probing questions such as “can you tell me more about it?” The interviews ended when no new data were found, and they were conducted by the main researcher (Mehrnoosh Khoshtrash) in a private room (mainly at the Imam Khomeini Hospital's Counseling Center in Tehran and Behavioral Disease Counseling Center of Guilan University of Medical Sciences in Rasht. The duration of the interviews was between 40 and 75 min (45 min on average). Data analysis is done simultaneously with data collection in qualitative studies. All interviews were transcribed, and MAXQDA software, version 10 was used for data management. For data analysis, the conventional content analysis method based on the proposed Graneheim and Lundman model was used [25].

Data rigor

In this qualitative research, many factors were taken into account to ensure trustworthiness. The Lincoln and Guba criteria were used to ensure the rigor of the data [26]. The most important strategies to ensure data trustworthiness were member check, peer check, external check, sampling with maximum variation, prolonged engagement during data collection and analysis, and accurately recording participants’ statements.

Results

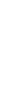

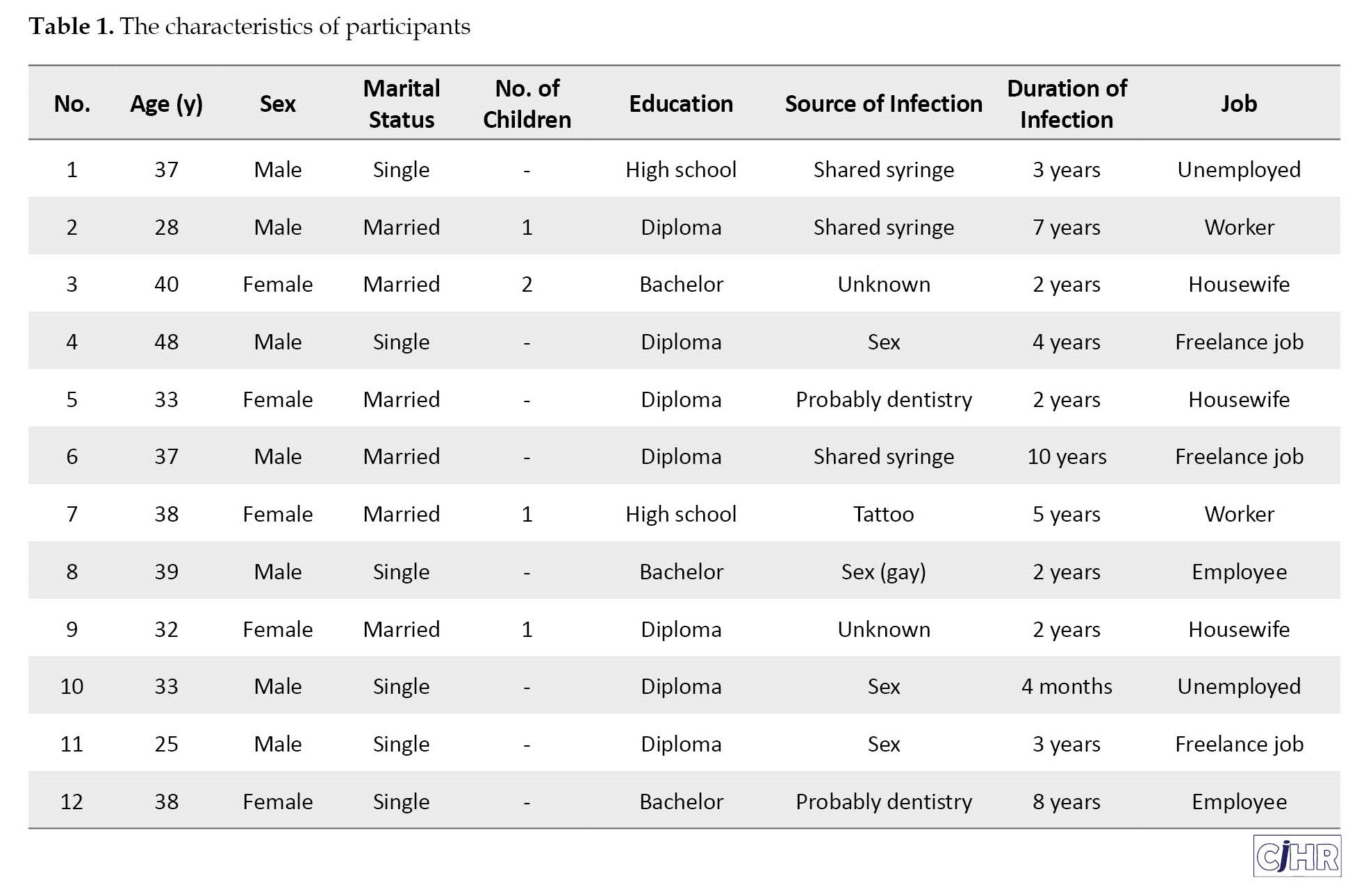

12 PLWHA participated in this study, whose characteristics are presented in Table 1.

An interview was conducted with each participant and none of the participants were excluded from the study. Based on the interview data analysis, 151 codes were extracted in three categories: Disease disclosure, social support, and acceptance.

Disease disclosure

This category includes three subcategories: Disease disclosure to important people in life, disclosure to public and health services, and dealing with the challenges of disclosure.

1. Disclosure to important people in life: The majority of participants disclosed their illness only to their immediate family and, in many cases, refused to reveal it to their relatives, friends, or even sexual partners. The main reason was their fear of the reaction: “No one knows about my illness except my wife, my father, my mother, and my sister. My brother and other family members don’t know about that. Even my daughter doesn’t know it. I get so nervous to tell her, but I feel she will fall apart. I’m always afraid that if I leave this world someday, what will they write about my death? HIV?” (P7). In some cases, because of the severe stigma, patients even refused to tell their immediate families: “My parents are religious people; if someone says this to me for the first time, I think badly... It’s so hard for me to tell them; I don’t want them to grieve” (P12).

Some participants highlighted the problems at the workplace and in their lives caused by disclosing the disease: “I didn’t want even my family to find out because there was no need for that. But my ex-wife revealed it at my workplace and in our neighborhood...; in my workplace, when my colleagues discovered my illness, I left there. They had some reactions, like separating my glass. Well, I felt upset. It also happened where I was living, so I couldn’t stay there any longer, and I had to live somewhere else....” (P2).

However, one patient discussed the importance of disclosing the disease to close relatives: “To those I have a relationship with, yeah, but not to those I see once in a blue moon. To friends I’m in touch with, yeah, because it can happen any time. Maybe one day, while walking together, I’ll faint and be injured, and my friend will come to help me, and his/her hand will be bloody. If his/her hand is injured, God forbid, it’ll be worse than death for me; I mean, it’s like dying every second. I prefer to tell them so that they will be alert if something happens at any time (P1).

2. Disclosure to public and health services: Due to feeling responsible for others, some participants disclosed their illness if they visited healthcare and public service centers, particularly when people were in contact with their blood and secretions, even though, in some cases, they had already experienced inappropriate reactions: “I went to the dentist several times, and I told about my illness; they were very welcoming and accepting. It didn’t matter to me even if they didn’t accept it because I didn’t want anyone else to have this problem. Even when I visit the doctor for a cold, I tell him, because we have gotten infected due to someone else’s mistake, why should another person be added to us?” (P12). A 39-year-old man said: “When you go to a clinic or a dentist, you must tell them about your disease. Not many patients disclose it, of course, but I do that. I consider it a mission for myself because I was also affected by another person’s ignorance. I mean, awareness must be created. So, I’ll disclose it wherever necessary” (P8). However, some participants refused to reveal it due to experiencing bad reactions or being afraid of it: “I went to the dentist; I wanted to say it, but my husband said that if I did it, they wouldn’t admit me, so I kept silent” (P5). Participant 10 stated: “For surgery, I told about my disease to the guy taking my blood sample; I said, but I regretted it because a woman from our hometown was there. Oh my God... his brother was my friend... I said, “Please don’t tell him about my illness.” But I was worried about it for a few days... I’ve decided not to say it even if I have an operation. The doctor himself must order this test.” Another participant said: “If I visit a doctor, I usually don’t say anything about my disease. They must take care of themselves, like sterilizing their equipment. My peer had that problem in the beginning. They were looking for the dentist, and I always told them not to tell anyone; it’s their duty. I used to say earlier, but now I don’t” (P6).

3. Dealing with the challenges of disclosure: Regarding this subcategory, one of the most important challenges that participants faced was the fear of disclosure and others’ reactions; therefore, in some cases, despite the available disease-related services in their hometown, they went to another city or place. In this regard, participant No. 4 stated: “In the family, only my brother knows about it... I couldn’t tell anyone otherwise; I wouldn’t have taken my medical record from the county here and spent so much money. No one can digest it...”. This issue was so serious that some patients decided to change their work and living places: “When my wife broke up, she unfairly disclosed everything at my workplace and where I and my family live. I had a problem at the workplace and had to leave... The same thing happened at my place of residence, and I couldn’t stay there anymore; I left for somewhere else” (P2).

Social support

This category includes the impairments in interpersonal relationships and communication with peers.

1. Impairment in interpersonal relationships: In this regard, some participants stated that since being infected, they restricted their interpersonal relationships and referred to the fear of disclosing the disease and others’ reactions as the main reasons: “I’ve locked myself at home because of others’ opinions and behavior... I’ve stayed at home... My main problem isn’t only physical; others’ opinions bother me more” (P1). Another participant stated: “From the moment I found it out, I’ve tried not to hang out with anyone too much because if they know about it, it will be bad for me... My friend told the others I had AIDS, and I haven’t hung out with them for a year and a half now. Maybe some will call and ask me to hang out with them, but I won’t do that” (P11).

Despite their willingness to maintain contact with others, some participants were rejected or met inappropriate reactions: “My kin’s behavior was a little strange... They separated my plate, glass, and spoon. I didn’t say anything. I avoided getting upset. They made various excuses not to take me out with them. I was very upset. I never went to their homes again, even though they invited me. For about a year, I didn’t go there” (P7). The other participant said, “But the relationships have changed; with my sister, it’s the same, but with my friends, yes; my mood has changed so much. I expected them to recognize this issue, but they didn’t care about it, and that’s why the distance was created” (P8). Participant No. 4 stated, “everybody runs away from you. Well, this isolates you. Nobody fears cancer. Family members hug the patient. They even kiss the corpse. But in the case of HIV, they think that if they pass ten meters away from you, they’ll get it!”

2. Communication with peers: Few participants in this study were in regular communication with peers to better accept the disease, obtain information, and help other patients. In this regard, one said: “I have two friends here (Positive Club). One of them had just taken medication, but he couldn’t hold his CD4 up. When they gave him medicine, he called me and said he was scared. I told him not to worry; I explained to him exactly what to do when he took the medicine… We usually speak our heart out” (P4). Another participant said, “It was really hard for me. Day and night, I thought, why me? My life is ruined. But seeing peers in the Positive Club and the groups we had helped me a lot” (P11). However, most participants were reluctant to communicate with their peers and attend the Positive Club, and they cited being busy, fear of further disclosure, more stress caused by increased awareness, and uselessness as the main reasons for it. One participant stated the following: “Here’s a Positive club that I don’t come to. I’ve had this problem for eight years now. I know everything, and I am very busy” (P12).

Acceptance

This category includes two subcategories: Social acceptance and acceptance by healthcare providers.

1. Social acceptance: All participants complained that society did not understand the disease properly and, in many cases, rejected or inappropriately treated the PLWHA. In this regard, participant No. 11 stated: “In society, it’s hard to tell that we have HIV because they treat us badly. There may be worse diseases than HIV, like cancer, but the name of this disease is bad. If you say, for example, someone has cancer, people say, oh God, heal them. But if you say HIV, they say, oh no; they may want to drown us. It means they are so pessimistic about us.”

2. Acceptance by healthcare providers: Most participants mentioned cases in which they were treated in a discriminatory manner by healthcare providers and were even prevented from being admitted and provided services. “Once I had a problem with my tooth. I visited two dentists; they refused to cure it. I went to the third place and did not talk about my illness, so the repair was done” (P2). Another participant said: “I had an accident some time ago. My uncle told them I had HIV and that they should care more. They didn’t come to my bedside at all until 2:00 PM; they didn’t even touch me. But I could see the patient in the bed beside me; they quickly visited him and asked about his problem. They were touching him, injecting him, and doing his work, but they didn’t come to me at all.” Some participants, however, stated that they were accepted by the staff at the time of disclosure: “ I went to the dentist several times and disclosed my illness, and they were very welcoming and accepting” (P12).

Discussion

In addition to living with chronic AIDS/AIDS, patients face numerous challenges in their personal relationships with family, friends, colleagues, and even health service providers. The experience of being labeled or socially marginalized is one of these patients’ life experiences. One of the most important challenges related to social interaction faced by participants was the fear of disclosing HIV infection and others’ reactions. For people living with HIV, the disclosure is a complex psychological state [27]. Although the disclosure may have several benefits, including increased self-confidence, increased psychological, social, and financial support, intimacy in relationships, safe sex, increased adherence to treatment, increased HIV test by sexual partners, improved access to HIV support centers, and the health of HIV-positive people, spouses, sexual partners, and society [28, 29], in HIV disease, disclosing the patient’s positive status is more challenging than in other diseases since it is not accepted in the society, and in some cultures, living with such a disease that requires changes in the lifestyle is difficult and challenging [30]. In this study, all the participants were too concerned about their illness being revealed to others, and some had not disclosed their illness to any of their family members. In some cases, patients had migrated from their place of residence due to fear of disclosure and rejection. This is despite the fact that in many developing countries, the family is the most important source of care during illness. AIDS has challenged this issue in many cases, and infected people have been rejected by their families. Our findings were consistent with other studies. For instance, 11% of participants in Nedjat’s study (2015) stated that none of their family members were aware of their illness [31]. In a study in South Africa (2012), 90% of the participants reported that, apart from healthcare providers, no one was aware of their condition [32]. In Wolf’s study (2006), 94% of individuals kept their disease hidden from the community. Of these, 69% did not reveal the disease to their families, and 20% did not even mention it to one person [33]. Adeniyi (2017) stated that only 20% of pregnant women referred to the hospital for delivery revealed the disease to their family members [34]. The findings of Philogen (2014) showed that almost half of patients had not revealed their illness to even one person [35]. In Esmaelzadeh’s (2018) study, HIV women living in the county stated that they traveled to the provincial centers for medication and services due to fear of exposure in the city, and they endured the hardship of traveling and not having a suitable place to stay, causing many problems for them, especially during pregnancy and delivery [36]. In other words, people with HIV/AIDS always find themselves in a stressful situation of hiding the disease and its disclosure to seek help. This offending condition prevents them from playing the role of a patient who could attract the attention and sympathy of others [37]. Participants in our study referred to the fear of rejection, discrimination, unemployment, and suffering among family members, as well as their experience in such cases, as the most important reasons for not disclosing the disease. Participants in the study by Esmaelzadeh (2017) likewise expressed the fear of rejection by family and sexual partners, as well as stigma and discrimination in society as factors influencing disease disclosure [36]. 27% of the PLWHA in the study by Wolf (2006), were afraid of unemployment due to the disclosure [33], and in Radfar’s research (2014), discrimination in the provision of healthcare services, coercion of the spouse, and fear of unemployment were among the most important obstacles to the disclosure [38]. Most of the participants in Rahmati’s study (2008) did not tell their family members about their illness because of the fear of being rejected, embarrassed, and upset [39]. This is despite the fact that not disclosing the disease increases its horizontal and vertical transmission [33] and causes problems such as non-adherence to treatment. As in the study by Li (2010), the most important reason for non-adherence to treatment (18%) was the fear of stigma caused by disclosing the illness [40].

However, it is known that the social relationships of PLWHA are affected at different levels with different dimensions and severity. Many participants in this study severely restricted their social relations and, in some cases, isolated themselves. In Zhang’s (2011) study, half of the PLWHA stated that the disease overshadowed their personal relationships with relatives or friends [11]. In Wolfe’s study (2006), 30% of PLWHA reported that their illness severely affected their interpersonal relationships [33]. In the study by Lekganyane (2012), PLWHA had isolated themselves and adopted concealment strategies to deal with the existing stigma [41]. However, even if affected individuals want to establish social relations with family members, friends, and the community, there is a possibility of being rejected by them. This finding was found in our study and in other studies. In the studies by Fallahi (2013) and Esmaeelzadeh (2018), some of the patients reported that they were rejected by their families for disclosing the disease [36, 42]. Meanwhile, advocacy groups formed by HIV-positive people play an important role in creating a positive identity against HIV and managing life with AIDS. Membership in these groups has provided psychological and emotional support to the PLWHA in the chronic condition. HIV-positive individuals claim that these support groups provide them with the opportunity to live with HIV, share their knowledge and experiences, and educate the community about HIV/AIDS. A number of participants have been in contact with their peers for better reception of the disease, obtaining relevant information, and helping other people with the disease, and they have attended counseling center training sessions. In Esmaeelzadeh’s (2016) study, some PLWHA considered participating in the center’s counseling classes as a factor for better acceptance of the disease, adaptation to the disease, and familiarity with other PLWHA [43].

Another issue that participants expressed was the need to be accepted in society, especially in the healthcare system. Many people complained not only about misunderstandings and attitudes in society but also about healthcare providers’ discriminatory behaviors and even their refusal to accept them. Furthermore, in the study by Tavakkol and Nickaeen (2012), most patients expressed annoyance and resentment about doctors’ discriminatory treatment and unequal access to healthcare services [44]. A study on 1,200 HIV-positive patients in Vietnam showed that most of them had experienced types of discrimination by healthcare centers, including preventing them from receiving health services, performing tests without consent, counseling on ceasing sexual relations and terminating pregnancies, and charging them higher for services [45]. A study on stigma and discrimination in Zambia also showed that HIV-positive people in healthcare centers face issues such as not being accepted for treatment, being delayed deliberately, being labeled, and being quickly discharged from the hospital to provide space for others [46]. This is despite the fact that there is considerable empirical evidence that stigma, discrimination, and fear of both are effective in increasing high-risk behaviors in PLWHA [47]. As in this study, a significant number of participants refused to disclose their illness when visiting healthcare centers, which increased the risk of disease transmission. In Esmaeelzadeh’s study (2018), almost all participants experienced discrimination by healthcare providers and doctors and, therefore, did not disclose their illness [36]. Disclosure requires the application of significant policies, including cultural counseling sensitivities in the context of HIV-positive individuals [48]. Healthcare providers should be aware that HIV disclosure is not uncomplicated; the context of disclosure and negative reactions to it need to be considered, and interventions to teach skills in response to these reactions should be implemented. Educational programs of communities and support groups to reduce stigma can improve HIV-positive individuals’ health [49].

Conclusion

The findings of this study indicate that despite all global and national efforts to raise awareness about HIV/AIDS, PLWHA continues to face numerous problems in their social interactions. The stigma around the world, and especially in Iran due to specific cultural conditions, is so high that it not only causes significant restrictions in PLWHA’s interpersonal relationships and even, in some cases, their isolation but also confronts these individuals with serious challenges in dealing with healthcare providers since in many cases they refuse to admit these patients or provide them with appropriate services. All of these suggest the need to pay special attention to PLWHA so that effective measures can be taken at the level of family, society, and healthcare systems to effectively interact with PLWHA and ultimately improve their mental and physical health. It is recommended to conduct descriptive-analytical studies in order to evaluate interpersonal relationships and social interactions of PLWHA and their problems.

Limitation

In general, research conducted on human subjects has limitations of recall, individual judgment, and the problem of time and place of interview, Therefore, the researchers tried to control this limitation by prior coordination with the participants.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1395.9221199206). All participants provided prior written informed consent and were informed of the right to withdraw from the study at any stage without negative consequences. They were assured that the interviews would be confidential and that results would be reported anonymously.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The report is part of the qualitative part of a larger study aimed at designing and validating health-related lifestyle tools in PLWHA. The authors tend to thank and appreciate the participants of this study as well as the personnel of the Behavioral Disease Counseling Center in Imam Khomeini Hospital, Tehran and Behavioral Disease Counseling Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences.

References

More than forty years have passed since the first reports on acquired immune deficiency virus (HIV). However, HIV infection remains a major global health problem [1]. HIV is an obstacle to the development of society and involves most of its active and productive population [2]. The importance of the disease can be visualized by the spread of an epidemic in 84.2 million people and 40.1 million deaths. In 2021, 1.5 million individuals worldwide contracted HIV, with six million living in Asia and Oceania [3]. Iran is also one of the most dangerous countries for HIV infection. Changes in the value system and social and economic structure in Iran have paved the way for new patterns of sexual behavior among Iranian youth [4]. Approximately 4100 new infections occur annually in Iran, and 2500 people die of this disease [5].

HIV/AIDS has affected patients’ physical, mental, and social health by creating various social problems, misconceptions in society, and social stigma [6]. Apart from living with a potentially life-threatening and chronic disease, people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) encounter numerous challenges, including the effect of the disease on their personal relationships with friends, family, colleagues, and healthcare providers [7]. Living with HIV/AIDS results in serious pressures on personal relationships, often leading to rejection and termination of relationships [8]. HIV Stigma affects the entire PLWHA family [9]. PLWHA’s social interactions with family members can become complicated, which often causes communication problems in the family [8]. HIV/AIDS also increases social isolation and rejection, avoidance by friends [8, 9], and separation by colleagues [8, 10]and worsens relationships with health professionals [11].

The impact of HIV/AIDS on social relations and support can have severe consequences for health condition of PLWHA. The importance of social support for HIV/AIDS has been widely documented. In general, strong social support is associated with slower disease progression, higher immune system performance [12, 13], and better adherence to treatment [14, 15, 16]. PLWHA, with strong social support networks, may employ more active coping strategies [17, 18] and enjoy better psychological well-being and mental health [19, 20]. The negative effect of HIV/AIDS stigma appears to be fading among people with strong social support networks [21]. Social support also plays a major role in improving HIV-positive individuals’ quality of life [22, 23, 24]. Although various quantitative and qualitative studies have studied the impact of PLWHA social relationships on their physical and mental health, and a number of qualitative studies have also examined aspects of PLWHA interpersonal relationships, there was no qualitative study that specifically and comprehensively examined PLWHA interpersonal relationships, especially in Iran, where family and social relationships are of particular importance. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the challenges faced by PLWHA in their daily social interactions.

Materials and Methods

The purpose of this qualitative content analysis was to determine the challenges of PLWHA in their daily social interactions. Data were collected from 12 PLWHA referring to the Behavioral Disease Counseling Center of Imam Khomeini Hospital, in Tehran and Behavioral Disease Counseling Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences in Rash City from April to September 2018. Purposive sampling and maximum variation were used to select participants. The inclusion criteria included speaking Persian and willingness to participate in the study. The first participant was selected based on her willingness to talk with the researcher. Semi-structured, face-to-face, recorded interviews were used for data collection. The research team designed an open-ended interview guide with the following questions: What social activities do you participate in? What is your relationship with others? Would you like to tell others about your disease? Questions and comments were followed up with probing questions such as “can you tell me more about it?” The interviews ended when no new data were found, and they were conducted by the main researcher (Mehrnoosh Khoshtrash) in a private room (mainly at the Imam Khomeini Hospital's Counseling Center in Tehran and Behavioral Disease Counseling Center of Guilan University of Medical Sciences in Rasht. The duration of the interviews was between 40 and 75 min (45 min on average). Data analysis is done simultaneously with data collection in qualitative studies. All interviews were transcribed, and MAXQDA software, version 10 was used for data management. For data analysis, the conventional content analysis method based on the proposed Graneheim and Lundman model was used [25].

Data rigor

In this qualitative research, many factors were taken into account to ensure trustworthiness. The Lincoln and Guba criteria were used to ensure the rigor of the data [26]. The most important strategies to ensure data trustworthiness were member check, peer check, external check, sampling with maximum variation, prolonged engagement during data collection and analysis, and accurately recording participants’ statements.

Results

12 PLWHA participated in this study, whose characteristics are presented in Table 1.

An interview was conducted with each participant and none of the participants were excluded from the study. Based on the interview data analysis, 151 codes were extracted in three categories: Disease disclosure, social support, and acceptance.

Disease disclosure

This category includes three subcategories: Disease disclosure to important people in life, disclosure to public and health services, and dealing with the challenges of disclosure.

1. Disclosure to important people in life: The majority of participants disclosed their illness only to their immediate family and, in many cases, refused to reveal it to their relatives, friends, or even sexual partners. The main reason was their fear of the reaction: “No one knows about my illness except my wife, my father, my mother, and my sister. My brother and other family members don’t know about that. Even my daughter doesn’t know it. I get so nervous to tell her, but I feel she will fall apart. I’m always afraid that if I leave this world someday, what will they write about my death? HIV?” (P7). In some cases, because of the severe stigma, patients even refused to tell their immediate families: “My parents are religious people; if someone says this to me for the first time, I think badly... It’s so hard for me to tell them; I don’t want them to grieve” (P12).

Some participants highlighted the problems at the workplace and in their lives caused by disclosing the disease: “I didn’t want even my family to find out because there was no need for that. But my ex-wife revealed it at my workplace and in our neighborhood...; in my workplace, when my colleagues discovered my illness, I left there. They had some reactions, like separating my glass. Well, I felt upset. It also happened where I was living, so I couldn’t stay there any longer, and I had to live somewhere else....” (P2).

However, one patient discussed the importance of disclosing the disease to close relatives: “To those I have a relationship with, yeah, but not to those I see once in a blue moon. To friends I’m in touch with, yeah, because it can happen any time. Maybe one day, while walking together, I’ll faint and be injured, and my friend will come to help me, and his/her hand will be bloody. If his/her hand is injured, God forbid, it’ll be worse than death for me; I mean, it’s like dying every second. I prefer to tell them so that they will be alert if something happens at any time (P1).

2. Disclosure to public and health services: Due to feeling responsible for others, some participants disclosed their illness if they visited healthcare and public service centers, particularly when people were in contact with their blood and secretions, even though, in some cases, they had already experienced inappropriate reactions: “I went to the dentist several times, and I told about my illness; they were very welcoming and accepting. It didn’t matter to me even if they didn’t accept it because I didn’t want anyone else to have this problem. Even when I visit the doctor for a cold, I tell him, because we have gotten infected due to someone else’s mistake, why should another person be added to us?” (P12). A 39-year-old man said: “When you go to a clinic or a dentist, you must tell them about your disease. Not many patients disclose it, of course, but I do that. I consider it a mission for myself because I was also affected by another person’s ignorance. I mean, awareness must be created. So, I’ll disclose it wherever necessary” (P8). However, some participants refused to reveal it due to experiencing bad reactions or being afraid of it: “I went to the dentist; I wanted to say it, but my husband said that if I did it, they wouldn’t admit me, so I kept silent” (P5). Participant 10 stated: “For surgery, I told about my disease to the guy taking my blood sample; I said, but I regretted it because a woman from our hometown was there. Oh my God... his brother was my friend... I said, “Please don’t tell him about my illness.” But I was worried about it for a few days... I’ve decided not to say it even if I have an operation. The doctor himself must order this test.” Another participant said: “If I visit a doctor, I usually don’t say anything about my disease. They must take care of themselves, like sterilizing their equipment. My peer had that problem in the beginning. They were looking for the dentist, and I always told them not to tell anyone; it’s their duty. I used to say earlier, but now I don’t” (P6).

3. Dealing with the challenges of disclosure: Regarding this subcategory, one of the most important challenges that participants faced was the fear of disclosure and others’ reactions; therefore, in some cases, despite the available disease-related services in their hometown, they went to another city or place. In this regard, participant No. 4 stated: “In the family, only my brother knows about it... I couldn’t tell anyone otherwise; I wouldn’t have taken my medical record from the county here and spent so much money. No one can digest it...”. This issue was so serious that some patients decided to change their work and living places: “When my wife broke up, she unfairly disclosed everything at my workplace and where I and my family live. I had a problem at the workplace and had to leave... The same thing happened at my place of residence, and I couldn’t stay there anymore; I left for somewhere else” (P2).

Social support

This category includes the impairments in interpersonal relationships and communication with peers.

1. Impairment in interpersonal relationships: In this regard, some participants stated that since being infected, they restricted their interpersonal relationships and referred to the fear of disclosing the disease and others’ reactions as the main reasons: “I’ve locked myself at home because of others’ opinions and behavior... I’ve stayed at home... My main problem isn’t only physical; others’ opinions bother me more” (P1). Another participant stated: “From the moment I found it out, I’ve tried not to hang out with anyone too much because if they know about it, it will be bad for me... My friend told the others I had AIDS, and I haven’t hung out with them for a year and a half now. Maybe some will call and ask me to hang out with them, but I won’t do that” (P11).

Despite their willingness to maintain contact with others, some participants were rejected or met inappropriate reactions: “My kin’s behavior was a little strange... They separated my plate, glass, and spoon. I didn’t say anything. I avoided getting upset. They made various excuses not to take me out with them. I was very upset. I never went to their homes again, even though they invited me. For about a year, I didn’t go there” (P7). The other participant said, “But the relationships have changed; with my sister, it’s the same, but with my friends, yes; my mood has changed so much. I expected them to recognize this issue, but they didn’t care about it, and that’s why the distance was created” (P8). Participant No. 4 stated, “everybody runs away from you. Well, this isolates you. Nobody fears cancer. Family members hug the patient. They even kiss the corpse. But in the case of HIV, they think that if they pass ten meters away from you, they’ll get it!”

2. Communication with peers: Few participants in this study were in regular communication with peers to better accept the disease, obtain information, and help other patients. In this regard, one said: “I have two friends here (Positive Club). One of them had just taken medication, but he couldn’t hold his CD4 up. When they gave him medicine, he called me and said he was scared. I told him not to worry; I explained to him exactly what to do when he took the medicine… We usually speak our heart out” (P4). Another participant said, “It was really hard for me. Day and night, I thought, why me? My life is ruined. But seeing peers in the Positive Club and the groups we had helped me a lot” (P11). However, most participants were reluctant to communicate with their peers and attend the Positive Club, and they cited being busy, fear of further disclosure, more stress caused by increased awareness, and uselessness as the main reasons for it. One participant stated the following: “Here’s a Positive club that I don’t come to. I’ve had this problem for eight years now. I know everything, and I am very busy” (P12).

Acceptance

This category includes two subcategories: Social acceptance and acceptance by healthcare providers.

1. Social acceptance: All participants complained that society did not understand the disease properly and, in many cases, rejected or inappropriately treated the PLWHA. In this regard, participant No. 11 stated: “In society, it’s hard to tell that we have HIV because they treat us badly. There may be worse diseases than HIV, like cancer, but the name of this disease is bad. If you say, for example, someone has cancer, people say, oh God, heal them. But if you say HIV, they say, oh no; they may want to drown us. It means they are so pessimistic about us.”

2. Acceptance by healthcare providers: Most participants mentioned cases in which they were treated in a discriminatory manner by healthcare providers and were even prevented from being admitted and provided services. “Once I had a problem with my tooth. I visited two dentists; they refused to cure it. I went to the third place and did not talk about my illness, so the repair was done” (P2). Another participant said: “I had an accident some time ago. My uncle told them I had HIV and that they should care more. They didn’t come to my bedside at all until 2:00 PM; they didn’t even touch me. But I could see the patient in the bed beside me; they quickly visited him and asked about his problem. They were touching him, injecting him, and doing his work, but they didn’t come to me at all.” Some participants, however, stated that they were accepted by the staff at the time of disclosure: “ I went to the dentist several times and disclosed my illness, and they were very welcoming and accepting” (P12).

Discussion

In addition to living with chronic AIDS/AIDS, patients face numerous challenges in their personal relationships with family, friends, colleagues, and even health service providers. The experience of being labeled or socially marginalized is one of these patients’ life experiences. One of the most important challenges related to social interaction faced by participants was the fear of disclosing HIV infection and others’ reactions. For people living with HIV, the disclosure is a complex psychological state [27]. Although the disclosure may have several benefits, including increased self-confidence, increased psychological, social, and financial support, intimacy in relationships, safe sex, increased adherence to treatment, increased HIV test by sexual partners, improved access to HIV support centers, and the health of HIV-positive people, spouses, sexual partners, and society [28, 29], in HIV disease, disclosing the patient’s positive status is more challenging than in other diseases since it is not accepted in the society, and in some cultures, living with such a disease that requires changes in the lifestyle is difficult and challenging [30]. In this study, all the participants were too concerned about their illness being revealed to others, and some had not disclosed their illness to any of their family members. In some cases, patients had migrated from their place of residence due to fear of disclosure and rejection. This is despite the fact that in many developing countries, the family is the most important source of care during illness. AIDS has challenged this issue in many cases, and infected people have been rejected by their families. Our findings were consistent with other studies. For instance, 11% of participants in Nedjat’s study (2015) stated that none of their family members were aware of their illness [31]. In a study in South Africa (2012), 90% of the participants reported that, apart from healthcare providers, no one was aware of their condition [32]. In Wolf’s study (2006), 94% of individuals kept their disease hidden from the community. Of these, 69% did not reveal the disease to their families, and 20% did not even mention it to one person [33]. Adeniyi (2017) stated that only 20% of pregnant women referred to the hospital for delivery revealed the disease to their family members [34]. The findings of Philogen (2014) showed that almost half of patients had not revealed their illness to even one person [35]. In Esmaelzadeh’s (2018) study, HIV women living in the county stated that they traveled to the provincial centers for medication and services due to fear of exposure in the city, and they endured the hardship of traveling and not having a suitable place to stay, causing many problems for them, especially during pregnancy and delivery [36]. In other words, people with HIV/AIDS always find themselves in a stressful situation of hiding the disease and its disclosure to seek help. This offending condition prevents them from playing the role of a patient who could attract the attention and sympathy of others [37]. Participants in our study referred to the fear of rejection, discrimination, unemployment, and suffering among family members, as well as their experience in such cases, as the most important reasons for not disclosing the disease. Participants in the study by Esmaelzadeh (2017) likewise expressed the fear of rejection by family and sexual partners, as well as stigma and discrimination in society as factors influencing disease disclosure [36]. 27% of the PLWHA in the study by Wolf (2006), were afraid of unemployment due to the disclosure [33], and in Radfar’s research (2014), discrimination in the provision of healthcare services, coercion of the spouse, and fear of unemployment were among the most important obstacles to the disclosure [38]. Most of the participants in Rahmati’s study (2008) did not tell their family members about their illness because of the fear of being rejected, embarrassed, and upset [39]. This is despite the fact that not disclosing the disease increases its horizontal and vertical transmission [33] and causes problems such as non-adherence to treatment. As in the study by Li (2010), the most important reason for non-adherence to treatment (18%) was the fear of stigma caused by disclosing the illness [40].

However, it is known that the social relationships of PLWHA are affected at different levels with different dimensions and severity. Many participants in this study severely restricted their social relations and, in some cases, isolated themselves. In Zhang’s (2011) study, half of the PLWHA stated that the disease overshadowed their personal relationships with relatives or friends [11]. In Wolfe’s study (2006), 30% of PLWHA reported that their illness severely affected their interpersonal relationships [33]. In the study by Lekganyane (2012), PLWHA had isolated themselves and adopted concealment strategies to deal with the existing stigma [41]. However, even if affected individuals want to establish social relations with family members, friends, and the community, there is a possibility of being rejected by them. This finding was found in our study and in other studies. In the studies by Fallahi (2013) and Esmaeelzadeh (2018), some of the patients reported that they were rejected by their families for disclosing the disease [36, 42]. Meanwhile, advocacy groups formed by HIV-positive people play an important role in creating a positive identity against HIV and managing life with AIDS. Membership in these groups has provided psychological and emotional support to the PLWHA in the chronic condition. HIV-positive individuals claim that these support groups provide them with the opportunity to live with HIV, share their knowledge and experiences, and educate the community about HIV/AIDS. A number of participants have been in contact with their peers for better reception of the disease, obtaining relevant information, and helping other people with the disease, and they have attended counseling center training sessions. In Esmaeelzadeh’s (2016) study, some PLWHA considered participating in the center’s counseling classes as a factor for better acceptance of the disease, adaptation to the disease, and familiarity with other PLWHA [43].

Another issue that participants expressed was the need to be accepted in society, especially in the healthcare system. Many people complained not only about misunderstandings and attitudes in society but also about healthcare providers’ discriminatory behaviors and even their refusal to accept them. Furthermore, in the study by Tavakkol and Nickaeen (2012), most patients expressed annoyance and resentment about doctors’ discriminatory treatment and unequal access to healthcare services [44]. A study on 1,200 HIV-positive patients in Vietnam showed that most of them had experienced types of discrimination by healthcare centers, including preventing them from receiving health services, performing tests without consent, counseling on ceasing sexual relations and terminating pregnancies, and charging them higher for services [45]. A study on stigma and discrimination in Zambia also showed that HIV-positive people in healthcare centers face issues such as not being accepted for treatment, being delayed deliberately, being labeled, and being quickly discharged from the hospital to provide space for others [46]. This is despite the fact that there is considerable empirical evidence that stigma, discrimination, and fear of both are effective in increasing high-risk behaviors in PLWHA [47]. As in this study, a significant number of participants refused to disclose their illness when visiting healthcare centers, which increased the risk of disease transmission. In Esmaeelzadeh’s study (2018), almost all participants experienced discrimination by healthcare providers and doctors and, therefore, did not disclose their illness [36]. Disclosure requires the application of significant policies, including cultural counseling sensitivities in the context of HIV-positive individuals [48]. Healthcare providers should be aware that HIV disclosure is not uncomplicated; the context of disclosure and negative reactions to it need to be considered, and interventions to teach skills in response to these reactions should be implemented. Educational programs of communities and support groups to reduce stigma can improve HIV-positive individuals’ health [49].

Conclusion

The findings of this study indicate that despite all global and national efforts to raise awareness about HIV/AIDS, PLWHA continues to face numerous problems in their social interactions. The stigma around the world, and especially in Iran due to specific cultural conditions, is so high that it not only causes significant restrictions in PLWHA’s interpersonal relationships and even, in some cases, their isolation but also confronts these individuals with serious challenges in dealing with healthcare providers since in many cases they refuse to admit these patients or provide them with appropriate services. All of these suggest the need to pay special attention to PLWHA so that effective measures can be taken at the level of family, society, and healthcare systems to effectively interact with PLWHA and ultimately improve their mental and physical health. It is recommended to conduct descriptive-analytical studies in order to evaluate interpersonal relationships and social interactions of PLWHA and their problems.

Limitation

In general, research conducted on human subjects has limitations of recall, individual judgment, and the problem of time and place of interview, Therefore, the researchers tried to control this limitation by prior coordination with the participants.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Iran University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1395.9221199206). All participants provided prior written informed consent and were informed of the right to withdraw from the study at any stage without negative consequences. They were assured that the interviews would be confidential and that results would be reported anonymously.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The report is part of the qualitative part of a larger study aimed at designing and validating health-related lifestyle tools in PLWHA. The authors tend to thank and appreciate the participants of this study as well as the personnel of the Behavioral Disease Counseling Center in Imam Khomeini Hospital, Tehran and Behavioral Disease Counseling Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences.

References

- De Cock KM, Jaffe HW, Curran JW. Reflections on 40 years of AIDS. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021; 27(6):1553-60. [DOI:10.3201/eid2706.210284] [PMID]

- Sadeghi R, Khanjani N. [Impact of educational intervention based on Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) on the AIDS-Preventive behavior among health volunteers (Persian)]. Iran J Health Educ Promot. 2015; 3(1):23-31. [Link]

- UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS statistics — fact sheet. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2022. [Link]

- AzadArmaki T, Sharifi Saei, MH. [Sociological explanation of anomic sexual relationships in Iran (Persian)]. J Fam Res. 2012; 7(4):435-62. [Link]

- SeyedAlinaghi S, Leila T, Mazaheri-Tehrani E, Ahsani-Nasab S, Abedinzadeh N, McFarland W, et al. HIV in Iran: Onset, responses and future directions. AIDS. 2021; 35(4):529-42. [DOI:10.1097/QAD.0000000000002757] [PMID]

- Aranda-Naranjo B. Quality of life in the HIV-positive patient: Implications and consequences. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2004; 15(5):20S-7S. [DOI:10.1177/1055329004269183] [PMID]

- Greene K, Frey LR, Derlega VJ. Interpersonalizing AIDS: Attending to the personal and social relationships of individuals living with HIV and/or AIDS. J Soc Pers Relat. 2002; 19(1):5-17. [DOI:10.1177/0265407502191001]

- Varas-Díaz N, Serrano-García I, Toro-Alfonso J. AIDS-related stigma and social interaction: Puerto Ricans living with HIV/AIDS. Qual Health Res. 2005; 15(2):169-87. [DOI:10.1177/1049732304272059] [PMID]

- Bogart LM, Cowgill BO, Kennedy D, Ryan G, Murphy DA, Elijah J, et al. HIV-related stigma among people with HIV and their families: A qualitative analysis. AIDS Behav. 2008; 12(2):244-54. [DOI:10.1007/s10461-007-9231-x] [PMID]

- Chesney MA, Smith AW. Critical delays in HIV testing and care: The potential role of stigma. Am Behav Sci. 1999; 42(7):1162-74. [DOI:10.1177/00027649921954822]

- Zhang Y, Zhang X, Hanko Aleong T, Fuller-Thomson E. Impact of HIV/AIDS on social relationships in Rural China. Open AIDS J. 2011; 5:67-73. [DOI:10.2174/1874613601105010067] [PMID]

- Leserman J, Jackson ED, Petitto JM, Golden RN, Silva SG, Perkins DO, et al. Progression to AIDS: The effects of stress, depressive symptoms, and social support. Psychosom Med. 1999; 61(3):397-406. [DOI:10.1097/00006842-199905000-00021] [PMID]

- Cohen M, Arad S, Lorber M, Pollack S. Psychological distress, life stressors, and social support in new immigrants with HIV. Behav Med. 2007; 33(2):45-54. [DOI:10.3200/BMED.33.2.45-54] [PMID]

- Catz SL, Kelly JA, Bogart LM, Benotsch EG, McAuliffe TL. Patterns, correlates, and barriers to medication adherence among persons prescribed new treatments for HIV disease. Health Psychol. 2000; 19(2):124-33. [DOI:10.1037/0278-6133.19.2.124] [PMID]

- Cox LE. Social support, medication compliance and HIV/AIDS. Soc Work Health Care. 2002; 35(1-2):425-60.[DOI:10.1300/J010v35n01_06] [PMID]

- Power R, Koopman C, Volk J, Israelski DM, Stone L, Chesney MA, et al. Social support, substance use, and denial in relationship to antiretroviral treatment adherence among HIV-infected persons. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2003; 17(5):245-52. [DOI:10.1089/108729103321655890] [PMID]

- Crystal S, Akincigil A, Sambamoorthi U, Wenger N, Fleishman JA, Zingmond DS, et al. The diverse older HIV-positive population: A national profile of economic circumstances, social support, and quality of life. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2003; 33:S76-83. [DOI:10.1097/00126334-200306012-00004]

- Onwumere J, Holttum S, Hirst F. Determinants of quality of life in black African women with HIV living in London. Psychol Health Med. 2002; 7(1):61-74. [DOI:10.1080/13548500120101568]

- Catz SL, Gore-Felton C, McClure JB. Psychological distress among minority and low-income women living with HIV. Behav Med. 2002; 28(2):53-60. [DOI:10.1080/08964280209596398] [PMID]

- Cowdery JE, Pesa JA. Assessing quality of life in women living with HIV infection. AIDS Care. 2002; 14(2):235-45. [DOI:10.1080/09540120220104730] [PMID]

- Galvan FH, Davis EM, Banks D, Bing EG. HIV stigma and social support among African Americans. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008; 22(5):423-36. [DOI:10.1089/apc.2007.0169] [PMID]

- Hays RB, Chauncey S, Tobey LA. The social support networks of gay men with AIDS. J Community Psychol. 1990; 18(4):374-85. [DOI:10.1002/1520-6629(199010)18:4<374::AID-JCOP2290180410>3.0.CO;2-C]

- Burgoyne R, Renwick R. Social support and quality of life over time among adults living with HIV in the HAART era. Soc Sci Med. 2004; 58(7):1353-66. [DOI:10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00314-9] [PMID]

- Gielen AC, McDonnell K, Wu AW, O’Campo P, Faden R. Quality of life among women living with HIV: The importance violence, social support, and self care behaviors. Soc Sci Med. 2001; 52(2):315-22. [DOI:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00135-0] [PMID]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004; 24(2):105-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001] [PMID]

- Speziale HS, Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative. revised ed. Philadelpia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [Link]

- Chaudoir SR, Fisher JD, Simoni JM. Understanding HIV disclosure: A review and application of the Disclosure Processes Model. Soc Sci Med. 2011; 72(10):1618-29. [DOI:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.03.028] [PMID]

- Gultie T, Genet M, Sebsibie G. Disclosure of HIV-positive status to sexual partner and associated factors among ART users in Mekelle hospital. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, NZ). 2015; 7:209-14. [DOI:10.2147/HIV.S84341] [PMID]

- Peretti-Watel P, Spire B, Pierret J, Lert F, Obadia Y; VESPA Group. Management of HIV-related stigma and adherence to HAART: Evidence from a large representative sample of outpatients attending French hospitals (ANRS-EN12-VESPA 2003). AIDS Care. 2006; 18(3):254-61. [DOI:10.1080/09540120500456193] [PMID]

- Visser MJ, Makin JD, Vandormael A, Sikkema KJ, Forsyth BW. HIV/AIDS stigma in a South African community. AIDS Care. 2009; 21(2):197-206. [DOI:10.1080/09540120801932157] [PMID]

- Nedjat S, Moazen B, Rezaei F, Hajizadeh S, Majdzadeh R, Setayesh HR, et al. Sexual and reproductive health needs of HIV-positive people in Tehran, Iran: A mixed-method descriptive study. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015; 4(9):591-8.[DOI:10.15171/ijhpm.2015.68] [PMID]

- Wekesa E. A new lease of life: Sexual and reproductive behaviour among PLWHA in the ART era in Nairobi slums [PhD dissertation]. London: London School of Economics and Political Science; 2012. [Link]

- Wolfe WR, Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, Thior I, Makhema JM, Dickinson DB, et al. Effects of HIV-related stigma among an early sample of patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Botswana. AIDS Care. 2006; 18(8):931-3. [DOI:10.1080/09540120500333558] [PMID]

- Adeniyi OV, Ajayi AI, Selanto-Chairman N, Goon DT, Boon G, Fuentes YO, et al. Demographic, clinical and behavioural determinants of HIV serostatus non-disclosure to sex partners among HIV-infected pregnant women in the eastern cape, South Africa. Plos One. 2017; 12(8):e0181730. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0181730] [PMID]

- Philogene J. Patterns of HIV serostatus disclosure among HIV-Positive young adults in Haiti: A mixed methods investigation [MAthesis]. Durham: Duke University; 2014. [Link]

- Saeieh SE, Ebadi A, Mahmoodi Z, Mohraz M, Nasrabadi AN, Moghadam ZB. Barriers to disclosure of disease in HIV-infected women: A qualitative study. HIV AIDS Rev Int J HIV Relat Probl. 2018; 17(1):12-7. [Link]

- Parvin S, Eslamian A. [The lived experience of women living with HIV in social relationships (Persian)]. Woman Dev Polit. 2014; 12(2):207-28. [Link]

- Radfar SR, Sedaghat A, Banihashemi AT, Gouya M, Rawson RA. Behaviors influencing human immunodeficiency virus transmission in the context of positive prevention among people living with HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Iran: A qualitative study. Int J Prev Med. 2014; 5(8):976-83. [PMID]

- Rahmati F, Niknami Sh, Amin shokravi F, Ahmadi F. [Perception and behaviour of AIDS patients: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Behbood. 2009; 13(3):220-34. [Link]

- Li L, Lee SJ, Wen Y, Lin C, Wan D, Jiraphongsa C. Antiretroviral therapy adherence among patients living with HIV/AIDS in Thailand. Nurs Health Sci. 2010; 12(2):212-20. [DOI:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00521.x] [PMID]

- Lekganyane R, du Plessis G. Dealing with HIV-related stigma: A qualitative study of women outpatients from the Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2012; 23(2):155-62. [DOI:10.1016/j.jana.2011.05.003] [PMID]

- Fallahi H, Tavafian S., Yaghmaie F, Hajizadeh E. [Consequences of living with hiv/aids: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Payesh. 2013; 12 (3):243-53. [Link]

- Behboodi-MoghadamZ, Esmaelzadeh-Saeieh S, Ebadi A, Nikbakht A, Mohraz M. Development and psychometric evaluation of a reproductive health assessment scale for HIV-positive women. Shiraz E-Med J. 2016; 17(6):e38489. [DOI:10.17795/semj38489]

- Tavakol M, Nikaeen D. [Stigmatization, doctor-patient relationship, and curing Hiv/Aids Patients (Persian)]. J Bioethics. 2012; 2(5):11-43. [Link]

- Messersmith LJ, Semrau K, Anh TL, Trang NN, Hoa DM, Eifler K, et al. Women living with HIV in Vietnam: Desire for children, use of sexual and reproductive health services, and advice from providers. Reprod Health Matters. 2012; 20(39 Suppl):27-38. [DOI:10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39640-7] [PMID]

- Bond V, Chase E, Aggleton P. Stigma, HIV/AIDS and prevention of mother-to-child transmission in Zambia. Eval Program Plann. 2002; 25(4):347-56. [DOI:10.1016/S0149-7189(02)00046-0]

- Doherty T, Chopra M, Nkonki L, Jackson D, Greiner T. Effect of the HIV epidemic on infant feeding in South Africa:” When they see me coming with the tins they laugh at me”. Bull World Health Organ. 2006; 84(2):90-6. [DOI:10.2471/BLT.04.019448] [PMID]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi L. Traditional beliefs about the cause of AIDS and AIDS-related stigma in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2004; 16(5):572-80. [DOI:10.1080/09540120410001716360] [PMID]

- Campbell C, Cornish F. Towards a “fourth generation” of approaches to HIV/AIDS management: Creating contexts for effective community mobilisation. AIDS Care. 2010; 22 (Suppl 2):1569-79. [DOI:10.1080/09540121.2010.525812] [PMID]

Article Type: Original Contributions |

Subject:

Public Health

Received: 2023/12/25 | Accepted: 2023/12/27 | Published: 2024/01/1

Received: 2023/12/25 | Accepted: 2023/12/27 | Published: 2024/01/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |