Volume 10, Issue 1 (1-2025)

CJHR 2025, 10(1): 63-72 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Eskandari F, Abedi ghlich ghashlaghi M. The Effects of Emotional Schema Therapy on Social Health and Attitude Towards Social Harms Among Female Students. CJHR 2025; 10 (1) :63-72

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-390-en.html

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-390-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Khomeinishahr Branch, Islamic Azad University, Khomeinishahr, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Khomeinishahr Branch, Islamic Azad University, Khomeinishahr, Iran. ,mld.abedi@yahoo.com

2- Department of Psychology, Khomeinishahr Branch, Islamic Azad University, Khomeinishahr, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 535 kb]

(304 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (816 Views)

Full-Text: (345 Views)

Introduction

Human beings are inherently complex, encompassing biological, psychological, and social dimensions. Understanding the factors influencing their growth and behavior is essential for fostering well-being and development [1]. In our country, where approximately 20% of the population is under the age of 15 and 30% is under the age of 30, the mental and social well-being of adolescents holds particular significance [2]. Adolescence represents a critical transitional phase from childhood to adulthood, marked by profound physiological, psychological, and social changes. This period can be both challenging and transformative for teenagers [3]. As the threshold to adulthood, adolescence plays a pivotal role in shaping individuals’ interactions with the world. The psychological and social impacts of this stage vary widely among individuals, underscoring the need for timely and tailored interventions [4]. Adolescence is considered a period of heightened risk due to the multitude of factors that can contribute to psychological and social issues, thus raising concerns among parents and professionals about the vulnerability of teenagers during this crucial time [2].

Currently, studies focusing on adolescents are considering not only the physical and mental health aspects but also the social aspects [5]. Social well-being might not be as familiar as physical or psychological health, but it is recognized as a crucial aspect of overall well-being alongside mental and physical wellness [6]. Social health is deemed more crucial and delicate than physical and mental health due to the continuous impact of factors that jeopardize it, unlike those that affect physical health, which have limited consequences. The threats to social health are closely tied to relationships, disrupting more than one individual [7]. The complexity and sensitivity of the issue lies in the fact that social health is not as easily noticeable as physical or mental health, as it manifests within various social relationships that are difficult to oversee or manage [8].

The societal problems are aspects of social life that involve structural conditions and behaviors evolving as societies change. These issues exist between where we are now and where we want to be, impeding progress and posing a threat to our values and aspirations [9]. A survey was conducted on 313 high school students, with ages ranging from 14 to 21 years and a mean age of 16.33 years with a standard deviation of 1.26 years. The study found that the prevalence of mental disorders among high school students was 51.11%, with girls reporting a significantly higher rate of 85.24% compared to boys [10]. Social harm is a complex issue that is challenging to succinctly describe. In broad terms, social harm refers to disturbances in society that are unwanted and inevitable, as well as the victimization of individuals due to the limitations imposed by social institutions, untreated preventable illnesses, and acts of injustice. These instances are commonly viewed as social problems, aligning closely with the expert definition of social harms [11]. Aggression, criminal activities, suicidal behaviors, substance abuse and illicit drug trade, prostitution, financial misconduct, and theft are instances of psychological and societal damage prevalent in contemporary Iranian society. The extent and impact of these issues vary based on factors such as time and location, for instance, comparing the present with the past or urban areas with rural areas. Consequently, what is perceived as harm or wrongdoing in a particular community today may not hold the same significance tomorrow or in a different society [12].

When an emotion arises, the initial action is to acknowledge and identify that emotion. In Leahy’s framework, the next step involves avoiding dealing with emotions both cognitively and emotionally [13]. In the field of psychopathology, many theorists and psychologists have attributed varying roles and positions to emotions when explaining mental disorders. Nowadays, in addition to eclectic models, numerous cognitive theories have also recognized the significant impact of emotions on the development and perpetuation of mental disorders. Consequently, many of these theories now view emotions as playing a crucial role alongside cognitions in the progression of mental disorders and have shifted towards emotional cognitive models [14]. Various studies have supported this approach across different populations. For instance, the impact of emotional schemas on the susceptibility of student teachers at Farhangian University of Mashhad to addiction was examined [15]. Similarly, research has examined the psychological, emotional, and social well-being of women in the families of martyrs experiencing persistent complex grief disorder [16]. Additionally, Hasanpour, Karimi Afshar, Soltaninejad, and Manzari Tavakoli (2023) ebplored the effects of emotional schemas on the social health and psychological resilience of nurses [17].

The primary focus of this study is on the implementation of emotional schema strategies, as outlined in Leahy’s theory of emotional schema therapy. Recognizing the significant role of emotions and their regulation in mental and social well-being, along with the emergence of societal issues, an examination of how this treatment impacts mental health and reduces susceptibility to social harms can contribute to enhancing overall societal welfare.

As social well-being becomes increasingly recognized globally as a key indicator of development and prosperity, defining research priorities on social health is crucial for shaping healthcare policies. Hence, the current research aims to assess the impact of emotional schema therapy on social health and attitudes towards social risks among teenage girls attending technical and vocational schools in Shahin Shahr’s.

Materials and Methods

Study type and population

The current research is a semi-experimental study with a pre-test, and post-test design involving a control group and a two-month follow-up. The study population for this study consisted of female students attending technical and vocational schools in Shahin Shahr in 2022. Thirty individuals through convenience sampling were selected. participants were divided into two experimental (n=15) and control group (n=15) using the dice throwing method. The adequacy of the sample size was determined using G*Power software, with the parameters set as follows: α=0.05, effect siz=0.40 [18] power=0.80, and number of groups=2. Based on these calculations, the required sample size was 28 participants. However, to account for potential dropouts, the researcher increased the sample size to 30 participants. Girls who scored above the mean on an attitude towards social harms questionnaire were included in the study (achieving a minimum score of 105 on the social harm attitude questionnaire). Participants were required to be between 16 and 18 years old, female students enrolled at technical and vocational schools in Shahin Shahr during 2022, provide informed consent, not participate in other concurrent interventions. Exclusion criteria included missing therapy sessions (over three), non-cooperation, failing to complete questionnaires, or expressing a desire to discontinue therapy.

Intervention protocol

To conduct this study, the researcher completed all necessary administrative procedures and obtained the code of ethics. Then, the researcher visited the girls ‘technical and vocational schools in Shahin Shahr and explained the purpose and importance of the research to the technical and vocational schools ‘s managers. Upon receiving approval, the researcher proceeded to select the sample and begin the study.

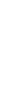

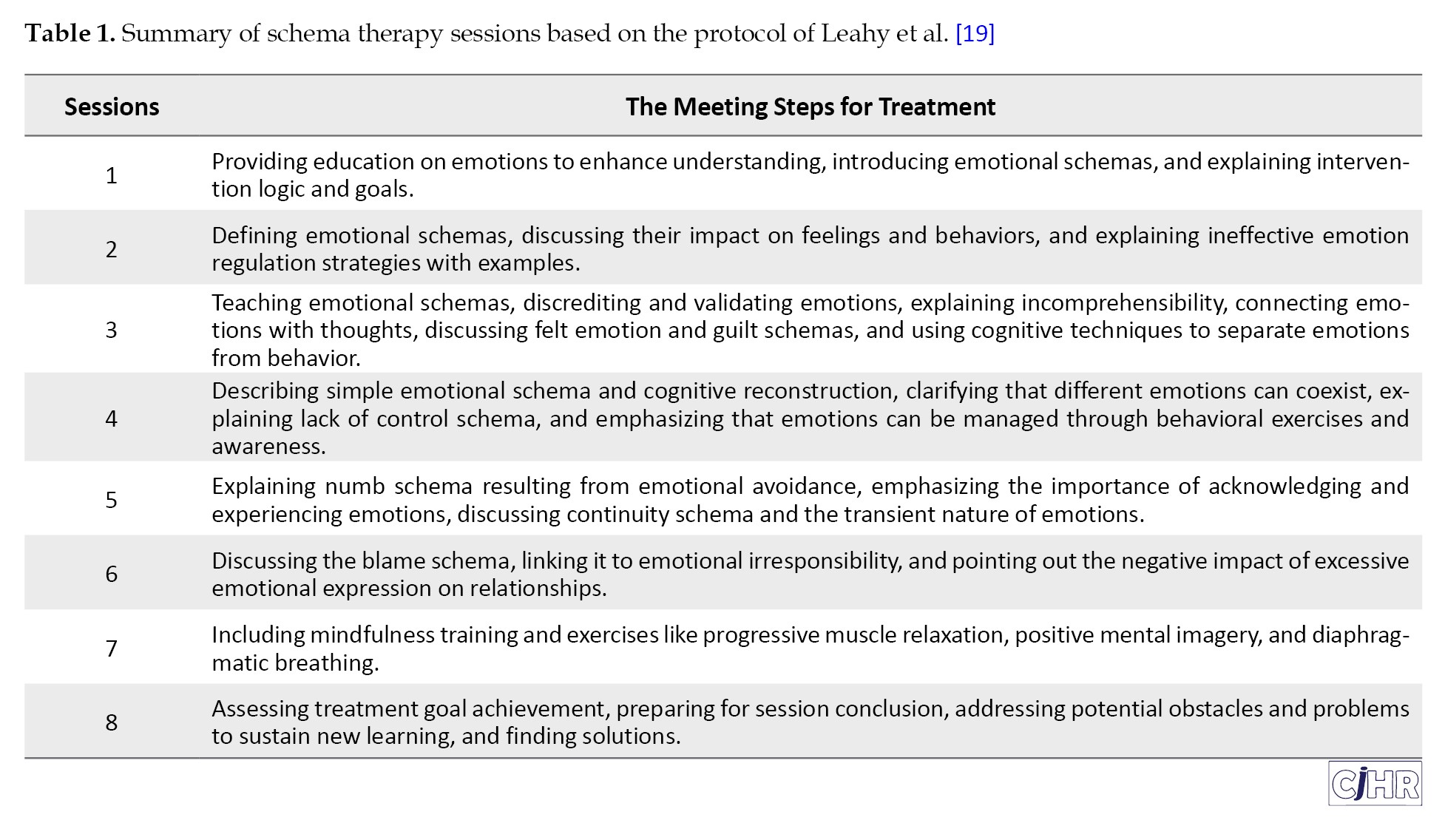

Emotional schema therapy intervention was conducted per week. The structure of the sessions followed the framework outlined by Leahy et al. (2011) [19]. The details of the meetings can be found in Table 1.

The experimental group members engaged in an 8-session emotional schema therapy educational intervention, lasting an hour and a half each. To implement the two intervention methods of the study, a 30-minute briefing session was held for the members of the experimental group before the start of the sessions, and the general principles, rules, and goals were discussed. Intervention sessions were conducted by the first author of this study and another psychotherapist with prior specialized training at the technical and vocational schools in Shahin Shahr, Iran, between Murch and May 2022. They underwent a post-test at the end of the sessions i.e. eight weeks after commencing of the study. The follow-up assessment was taken two months later. The control group did not receive any intervention, only pre-test, post-test, and follow-up assessments were administered. Two months later, follow-up questionnaires were given to the experimental group members. The responses to each questionnaire were thoroughly reviewed for accuracy. Data necessary to evaluate the research goals and hypotheses were extracted from these questionnaires and analyzed statistically. In this study, ethical considerations were taken into account by ensuring the anonymity of each respondent to prevent any potential negative outcomes. To ensure ethical considerations, participants were required to provide personal consent and express their willingness to take part in the research.

Research tools

Attitude towards social harms questionnaire (ATSH): This questionnaire is a self-administered questionnaire that is designed based on the dimensions of social harm identified in the research of Jangi Sangani and Razavi in 2024 [20]. The purpose of the questionnaire questions is to evaluate students’ attitudes towards various social issues, which includes 42 questions with five answer options from completely agree to completely disagree. The scores range from 42 to 210, and higher scores indicate greater awareness of the negative consequences that may arise from social interactions. Social harms in the questionnaire include theft, violence, drug abuse, sexual issues, suicide and running away from home. The reliability of the questionnaire was obtained using Cronbach’s α of 0.85, while the validity of the questionnaire was obtained and confirmed using the average variance (AVE) index of 0.54. Likewise, the factorial of the questions was higher than 0.7 [20].

Social well-being questionnaire (SWQ): In 1998, Keyes developed a SWQ consisting of 33 items, following his theoretical model of social well-being structure [21]. This questionnaire is commonly utilized in social health psychology to assess social well-being levels. The questionnaire includes dimensions such as social prosperity, social cohesion, social participation, social solidarity, and social acceptance. The subscale “social cohesion” comprises items 2, 9, 10, 12, 16, and 21, while “social solidarity” includes items 3, 4, 24, 26, 28, and 32. Items 5, 7, 15, 17, 18, 25, and 30 measure the subscale of “social prosperity”, and items 6, 8, 14, 19, 23, and 31 measure the “social acceptance”. Participants rate these items on a five-point Likert scale ranging from completely agree (5) to completely disagree (1). Scores on the questionnaire can range from 33 to 165, with a cutoff score of 82.5.

Higher scores indicate better social health. Keyes conducted two studies involving 373 individuals in the United States to validate his findings, using factor analysis of the 5-dimensional model. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s α coefficient, which was reported as 0.85 by Keyes and as 0.76 [21, 22]. Likewise, the content validity of the questionnaire in Iran was examined in research in which the scale was translated and then qualitatively confirmed by eight professors of the psychology department. The construct validity of the questionnaire was also calculated based on the correlation coefficients between the subscales and the total score, and the relationship between social well-being and the dimensions of social solidarity, social cohesion, social participation, social flourishing, and social acceptance was found to be 0.707, 0.608, 0.753, 0.771, and 0.737, respectively [23]. At the same time, the reliability of the questionnaire using Cronbach’s α coefficient in the present study was equal to 0.71.

Statistical analysis

The survey questionnaire data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive analysis included frequencies, percentages, and measures of central tendency and dispersion (Mean±SD). Inferential analysis involved Shapiro’s test for normality, Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances, and repeated measures analysis of covariance. The results were presented according to the group-by-time interaction. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 28.

Results

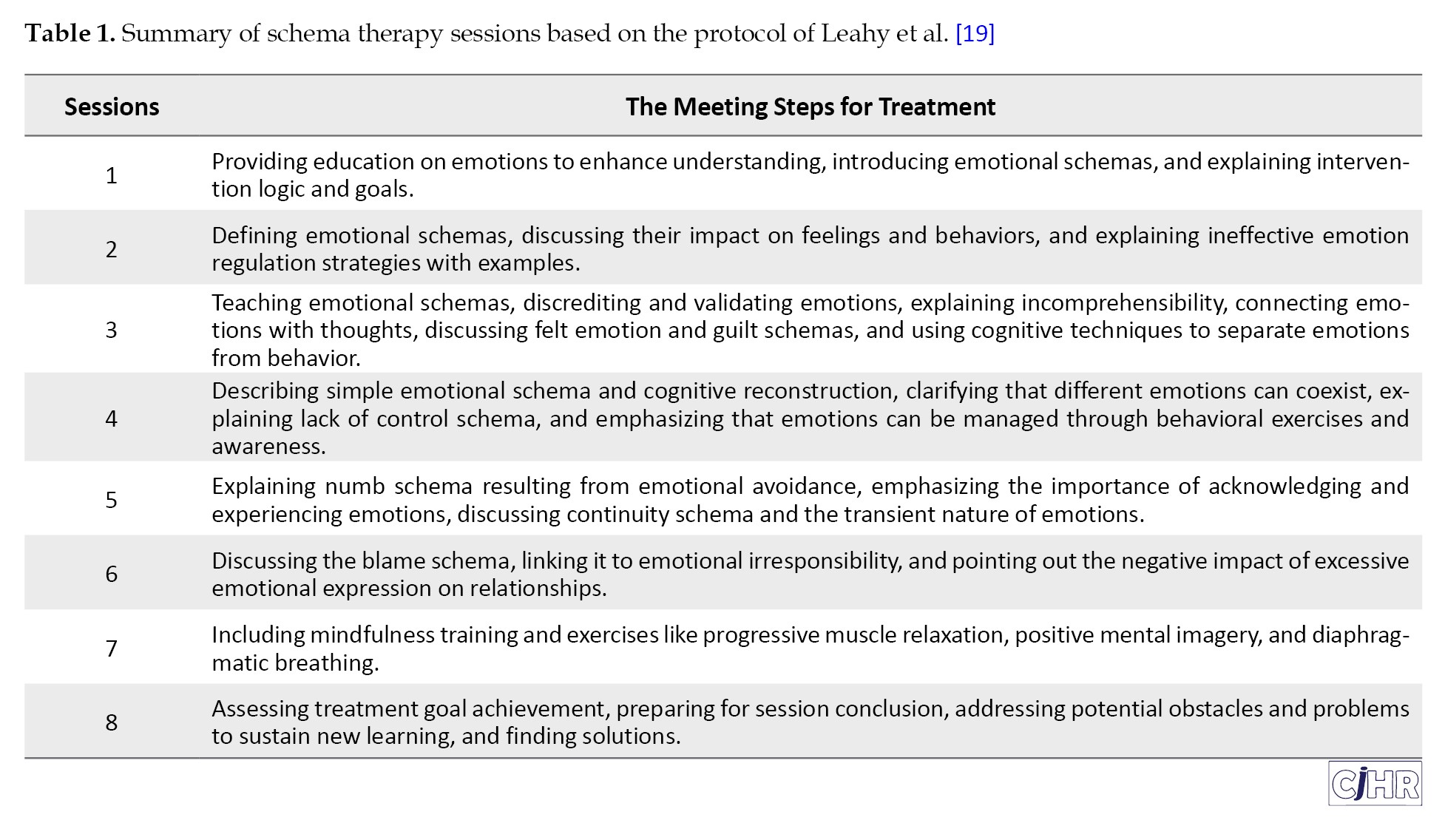

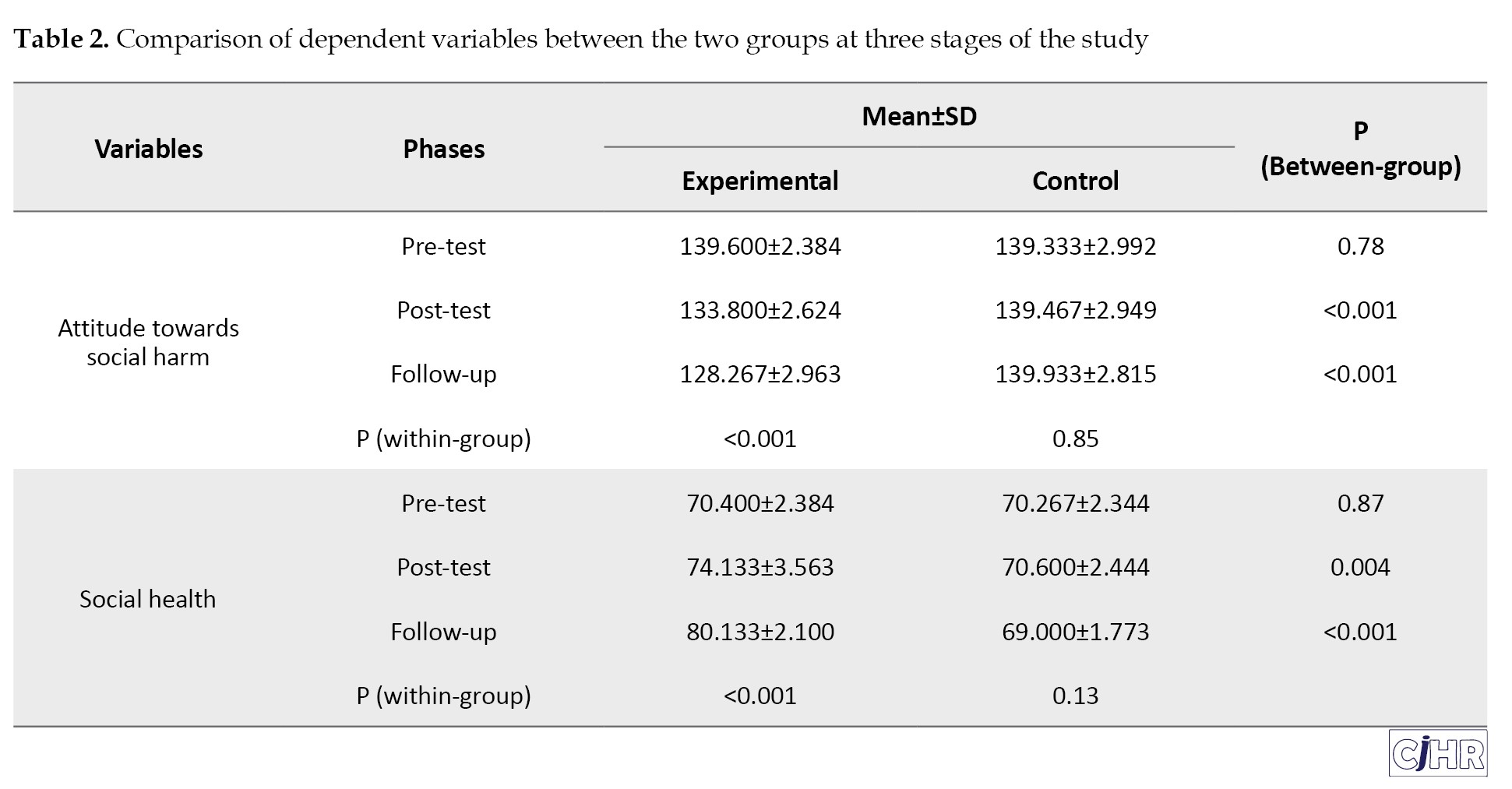

The Mean±SD age of study participants was 16.2±1.27 years. In terms of the number of family children, 40% of participants in the experimental group and 47% in the control group were the only child in their family. There was no significant difference in the number of siblings (P=0.75) and parental education between the two groups (P=0.87). Table 2 shows the Mean±SD of research outcomes between the two groups at three stages of the study.

The pre-test values of both variables were not significantly different between the two groups. The mean scores of social harms in the experimental group decreased in the post-test and Follow-up stages compared to baseline while these values were similar in the control group in all 3 stages.

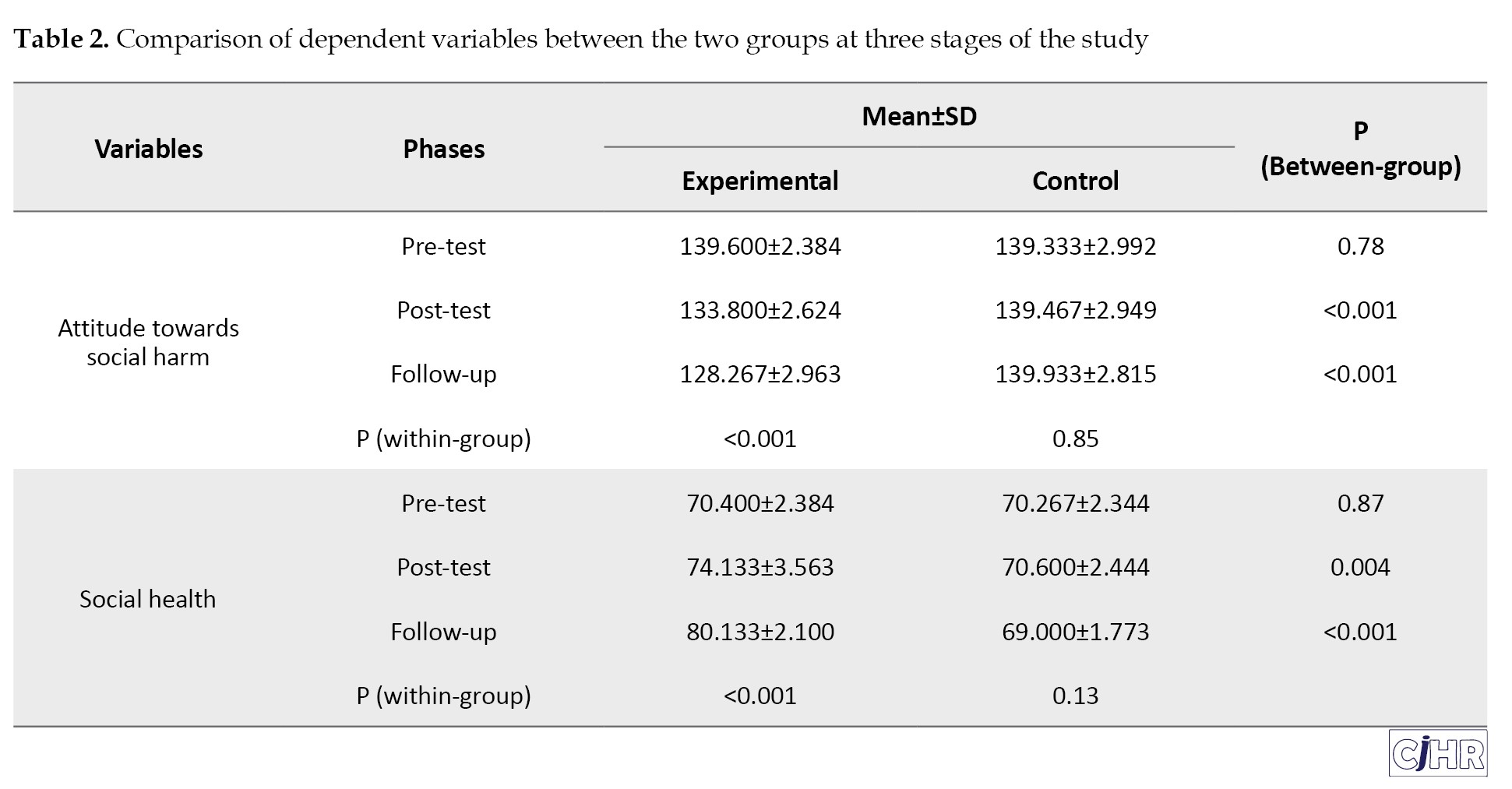

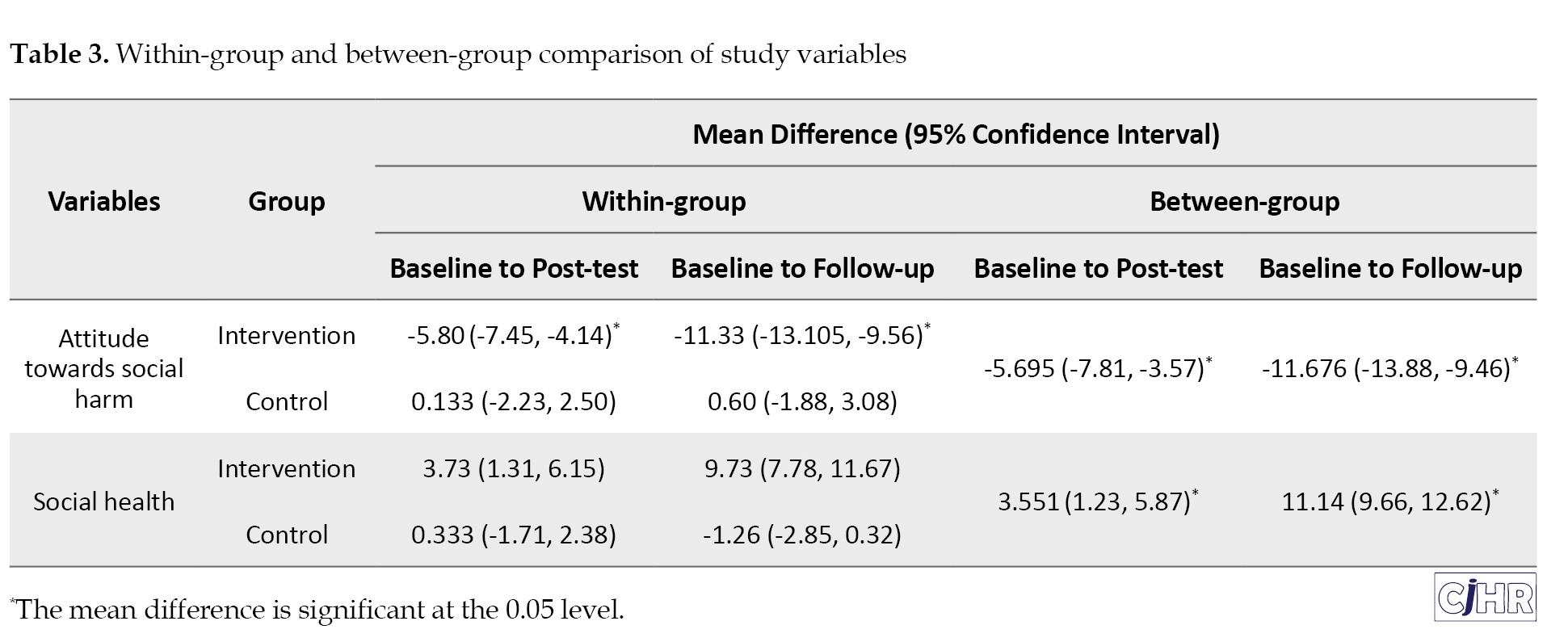

According to the findings from the repeated measure covariance analysis presented in Table 3, attitude toward social harm demonstrated a significant group-by-time interaction (F=22.98, P<0.001, η2=0.46), Consequently, separate pairwise analysis were conducted.

The experimental group showed a significant decrease in social harm score at both the post-test and follow-up stage compared to the pre-test (P<0.05). In contrast, the control group didn’t exhibit any significance over time. Similarly, there was a significant group-by-time interaction (F=29.97, P<0.001, η2=0.53) in social health with the experimental group indicating significantly improvement in social health over time (9.37; 95% CI, 7.78%, 11.67%), while the control group did not show a significant change over time (-1.26; 95% CI, -2.85 %, 0.32%). The between-group mean difference in social harm scores from pre-test to post-test was -5.695 (95% CI, -7.81%, -3.57%), indicating a statistically significant reduction in the experimental group compared to the control group. Greater between-group reduction was also found from baseline to follow-up -11.676 (-13.88% to -9.46%). The between-group mean difference in social health scores from pre-test to post-test was 3.551 (95% CI, 1.23% to 5.87%), indicating a statistically significant improvement in the experimental group compared to the control group. A higher between-group improvement was reported from baseline to follow-up 11.14 (95% CI, 9.66% to 12.62%).

Discussion

The primary objective of the current study was to assess the impact of emotional schema therapy on social health and attitudes towards social issues among teenage girls attending conservatories in Shahin Shahr. Emotional schema therapy was found to have a positive effect on the social health of adolescent girls enrolled in conservatories in Shahin Shahr. These findings are in line with previous research conducted by Ataei et al. (2024), Azizi and Saffarinia (2018), and Tashke et al. [17, 24, 25]. The results from studies by Vermziari et al. (2021), Morwaridi et al. (2018), and Penny and Norton (2022) also indicated that schema therapy can enhance social health in individuals with personality disorders or depression [26-28]. Schemas are established and long-lasting structures that develop because of unmet emotional needs during childhood. These schemas are abstract representations of key features of an event that influence an individual’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors in future intimate relationships and other areas of their lives. They are constructed based on real-life experiences to help individuals make sense of their encounters. Through the utilization of cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques, attachment theory, and Gestalt therapy relationship analysis, a new therapeutic model has been introduced for addressing personality disorders and chronic conditions. Schemas are flawed emotional and cognitive patterns that originate in childhood and persist throughout one’s life. Many of the behaviors exhibited by individuals today stem from difficulties faced during childhood and adolescence. The school of constructivism emerged because of the challenges in effectively treating psychological issues like personality disorders. The history of psychotherapy reveals the complexities involved in treating individuals with personality disorders, making it essential for therapists to employ this treatment approach [17].

The findings suggest that schema therapy effectively reduces the impact of schemas across all areas, leading to a significant improvement in social well-being and enhancement in social adjustment. Schemas are fundamental in the development of psychological issues, disorders, and dysfunctional behaviors in individuals, believed to be ineffective and self-sustaining. They compel individuals to act inconsistently based on distorted perceptions that persist throughout their lives. Schema therapy is thought to address various types of schemas, resulting in the amelioration of psychological issues like social alienation and disrupted interpersonal connections. Unhealthy self-perceptions and negative self-images are exacerbated by schemas, diminishing social engagement, solidarity, and acceptance [28]. Incompatible schemas foster social exclusion and the breakdown of familial and societal support systems, instigating negative self-perceptions that lower social well-being. Schemas contribute significantly to heightened stress, anxiety, and pessimistic thoughts, impacting the physical, mental, and social well-being of individuals. Schemas can be viewed as cognitive structures that store generalized concepts or a structured repository of information, beliefs, and assumptions that mitigate concerns related to negative beliefs and self-criticism, therefore enhancing social health [26, 27].

The research results indicate that emotional schema therapy has an impact on the attitudes towards social harms (such as theft, aggression, drugs, sexual issues, suicide, and running away from home) of teenage girls attending conservatories in Shahin Shahr City. These findings are consistent with the research conducted by Sedaghati and Saraei, as well as Karatzias et al. (2016), Sedaghati Rad et al. (2021), and Dadomo et al. (2018) [15, 29, 30]. Another study by Ghaderi et al. (2016) explored the effects of group schema therapy on the cognitive emotion regulation strategies of students, demonstrating that schema therapy influences cognitive emotion regulation strategies like aggression, self-blame, blame of others, positive reappraisal, catastrophizing, rumination, and effective planning refocusing [31]. The results of this study align with previous research by Dadomo et al. (2018) and Bär et al (2023), which highlight the effectiveness of schema therapy on aggression [29, 32]. Schemas tend to bias human interpretations of events, leading to misunderstandings, distorted attitudes, false assumptions, and unrealistic expectations that reinforce schemas by emphasizing data that supports them while ignoring or downplaying conflicting information. Individuals displaying signs of aggression often possess a schema mindset that triggers aggressive behavior without considering potential consequences, becoming highly sensitive in certain situations that activate these schemas and provoke disturbing emotions, avoidance responses, or harmful actions. This therapeutic approach aims to help individuals identify their incompatible schema mindset and understand the behaviors that perpetuate their schemas, such as avoidance, submission, and extreme compensation [29, 33].

Schema therapy is effective and efficient as it addresses multiple aspects of a person, including cognitive, experiential, emotional, and behavioral dimensions, providing a framework for change. By focusing on the internalized voice of parents and deep-rooted schemas in the cognitive dimension, schema therapy helps individuals understand the origins of their thoughts and challenges the validity of these schemas, leading to a new perspective on themselves and the world. This therapy also helps identify unhealthy patterns and behaviors, allowing individuals to replace them with healthier alternatives, leading to increased self-awareness and improved interpersonal relationships [29].

Experimental techniques also assist patients in emotional reorganization, self-assessment of new knowledge, interpersonal emotion regulation, and self-relaxation to lay the foundation for schema enhancement. Individuals can utilize these techniques to examine the hypotheses of schemas, stimulate the schemas, and connect them to current issues, thereby facilitating emotional insight and subsequent schema improvement. The use of mental imagery enables individuals to identify key schemas, comprehend their evolutionary origins, and link these origins to their present lives. Furthermore, it enhances understanding and facilitates the transition from logical thinking to emotional experience [29]. Through multiple discussions, the emergence of primary emotions such as anger creates a platform for emotional release and helps individuals detach from schemas. By employing mental imagery to disrupt patterns, individuals distance themselves from coping mechanisms characterized by extreme avoidance and compensation. Moreover, using the method of writing letters allows individuals the opportunity to assert their rights and acknowledge their emotions. When emotional needs are partially met during treatment, it sets the stage for schema improvement, as incompatible schemas typically arise from unmet emotional needs. Essentially, in the realm of emotions, schema therapy challenges the cognitive-experiential strategies linked to emotional beliefs, enabling individuals to combat their schemas not only at the cognitive level but also on an emotional plane. This technique aids in emotional release by helping individuals recognize their unmet emotional needs that contribute to the development of schemas [30].

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this study, emotional schema therapy has a positive impact on social health among adolescent girls attending conservatories in Shahin Shahr city. By offering schema therapy workshops in schools, there should be an effort to enhance social health to assist individuals in adapting better to challenges. The study results indicate that group schema therapy is effective in altering attitudes toward social issues among female students at Shahin Shahr’s technical and vocational schools.

The results of this research only applied to female students attending Shahin Shahr’s technical and vocational schools, so any projections should be approached with caution and a thorough understanding. Given that the participants were chosen from those easily accessible, there is a possibility that it may not accurately represent the whole population. The use of a questionnaire rather than interviews raises the risk of tracking the responses provided and their potential connection to the study’s goals. Subsequent studies should focus on measuring more impactful variables. It is suggested that the current study be carried out with a larger sample size and across a wider geographic area to provide a more comprehensive insight into how the variables in question are employed. Future studies should include a longer follow-up period, such as 3 or 6 months, for a more detailed examination. Training in schema therapy, combined with cognitive and emotional techniques, is believed to change schemas. Managing emotions and reducing negative feelings such as aggression can improve the psychological well-being and overall quality of life of individuals who undergo this type of therapy. Therefore, it is recommended that the delivery of such services be incorporated into the educational agenda, particularly for female high school students. Given the target population (students) who face various risk factors for substance abuse, the integration of schema therapy as a preventative measure in high schools can be a means to mitigate the rise in substance abuse and other social problems associated with it in this demographic.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The present work obtained ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Islamic Azad University, Khomeinishahr Branch, Khomeinishahr, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.KHSH.REC.1402.013).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to sincerely thank all the individuals who participated in this research.

References

Human beings are inherently complex, encompassing biological, psychological, and social dimensions. Understanding the factors influencing their growth and behavior is essential for fostering well-being and development [1]. In our country, where approximately 20% of the population is under the age of 15 and 30% is under the age of 30, the mental and social well-being of adolescents holds particular significance [2]. Adolescence represents a critical transitional phase from childhood to adulthood, marked by profound physiological, psychological, and social changes. This period can be both challenging and transformative for teenagers [3]. As the threshold to adulthood, adolescence plays a pivotal role in shaping individuals’ interactions with the world. The psychological and social impacts of this stage vary widely among individuals, underscoring the need for timely and tailored interventions [4]. Adolescence is considered a period of heightened risk due to the multitude of factors that can contribute to psychological and social issues, thus raising concerns among parents and professionals about the vulnerability of teenagers during this crucial time [2].

Currently, studies focusing on adolescents are considering not only the physical and mental health aspects but also the social aspects [5]. Social well-being might not be as familiar as physical or psychological health, but it is recognized as a crucial aspect of overall well-being alongside mental and physical wellness [6]. Social health is deemed more crucial and delicate than physical and mental health due to the continuous impact of factors that jeopardize it, unlike those that affect physical health, which have limited consequences. The threats to social health are closely tied to relationships, disrupting more than one individual [7]. The complexity and sensitivity of the issue lies in the fact that social health is not as easily noticeable as physical or mental health, as it manifests within various social relationships that are difficult to oversee or manage [8].

The societal problems are aspects of social life that involve structural conditions and behaviors evolving as societies change. These issues exist between where we are now and where we want to be, impeding progress and posing a threat to our values and aspirations [9]. A survey was conducted on 313 high school students, with ages ranging from 14 to 21 years and a mean age of 16.33 years with a standard deviation of 1.26 years. The study found that the prevalence of mental disorders among high school students was 51.11%, with girls reporting a significantly higher rate of 85.24% compared to boys [10]. Social harm is a complex issue that is challenging to succinctly describe. In broad terms, social harm refers to disturbances in society that are unwanted and inevitable, as well as the victimization of individuals due to the limitations imposed by social institutions, untreated preventable illnesses, and acts of injustice. These instances are commonly viewed as social problems, aligning closely with the expert definition of social harms [11]. Aggression, criminal activities, suicidal behaviors, substance abuse and illicit drug trade, prostitution, financial misconduct, and theft are instances of psychological and societal damage prevalent in contemporary Iranian society. The extent and impact of these issues vary based on factors such as time and location, for instance, comparing the present with the past or urban areas with rural areas. Consequently, what is perceived as harm or wrongdoing in a particular community today may not hold the same significance tomorrow or in a different society [12].

When an emotion arises, the initial action is to acknowledge and identify that emotion. In Leahy’s framework, the next step involves avoiding dealing with emotions both cognitively and emotionally [13]. In the field of psychopathology, many theorists and psychologists have attributed varying roles and positions to emotions when explaining mental disorders. Nowadays, in addition to eclectic models, numerous cognitive theories have also recognized the significant impact of emotions on the development and perpetuation of mental disorders. Consequently, many of these theories now view emotions as playing a crucial role alongside cognitions in the progression of mental disorders and have shifted towards emotional cognitive models [14]. Various studies have supported this approach across different populations. For instance, the impact of emotional schemas on the susceptibility of student teachers at Farhangian University of Mashhad to addiction was examined [15]. Similarly, research has examined the psychological, emotional, and social well-being of women in the families of martyrs experiencing persistent complex grief disorder [16]. Additionally, Hasanpour, Karimi Afshar, Soltaninejad, and Manzari Tavakoli (2023) ebplored the effects of emotional schemas on the social health and psychological resilience of nurses [17].

The primary focus of this study is on the implementation of emotional schema strategies, as outlined in Leahy’s theory of emotional schema therapy. Recognizing the significant role of emotions and their regulation in mental and social well-being, along with the emergence of societal issues, an examination of how this treatment impacts mental health and reduces susceptibility to social harms can contribute to enhancing overall societal welfare.

As social well-being becomes increasingly recognized globally as a key indicator of development and prosperity, defining research priorities on social health is crucial for shaping healthcare policies. Hence, the current research aims to assess the impact of emotional schema therapy on social health and attitudes towards social risks among teenage girls attending technical and vocational schools in Shahin Shahr’s.

Materials and Methods

Study type and population

The current research is a semi-experimental study with a pre-test, and post-test design involving a control group and a two-month follow-up. The study population for this study consisted of female students attending technical and vocational schools in Shahin Shahr in 2022. Thirty individuals through convenience sampling were selected. participants were divided into two experimental (n=15) and control group (n=15) using the dice throwing method. The adequacy of the sample size was determined using G*Power software, with the parameters set as follows: α=0.05, effect siz=0.40 [18] power=0.80, and number of groups=2. Based on these calculations, the required sample size was 28 participants. However, to account for potential dropouts, the researcher increased the sample size to 30 participants. Girls who scored above the mean on an attitude towards social harms questionnaire were included in the study (achieving a minimum score of 105 on the social harm attitude questionnaire). Participants were required to be between 16 and 18 years old, female students enrolled at technical and vocational schools in Shahin Shahr during 2022, provide informed consent, not participate in other concurrent interventions. Exclusion criteria included missing therapy sessions (over three), non-cooperation, failing to complete questionnaires, or expressing a desire to discontinue therapy.

Intervention protocol

To conduct this study, the researcher completed all necessary administrative procedures and obtained the code of ethics. Then, the researcher visited the girls ‘technical and vocational schools in Shahin Shahr and explained the purpose and importance of the research to the technical and vocational schools ‘s managers. Upon receiving approval, the researcher proceeded to select the sample and begin the study.

Emotional schema therapy intervention was conducted per week. The structure of the sessions followed the framework outlined by Leahy et al. (2011) [19]. The details of the meetings can be found in Table 1.

The experimental group members engaged in an 8-session emotional schema therapy educational intervention, lasting an hour and a half each. To implement the two intervention methods of the study, a 30-minute briefing session was held for the members of the experimental group before the start of the sessions, and the general principles, rules, and goals were discussed. Intervention sessions were conducted by the first author of this study and another psychotherapist with prior specialized training at the technical and vocational schools in Shahin Shahr, Iran, between Murch and May 2022. They underwent a post-test at the end of the sessions i.e. eight weeks after commencing of the study. The follow-up assessment was taken two months later. The control group did not receive any intervention, only pre-test, post-test, and follow-up assessments were administered. Two months later, follow-up questionnaires were given to the experimental group members. The responses to each questionnaire were thoroughly reviewed for accuracy. Data necessary to evaluate the research goals and hypotheses were extracted from these questionnaires and analyzed statistically. In this study, ethical considerations were taken into account by ensuring the anonymity of each respondent to prevent any potential negative outcomes. To ensure ethical considerations, participants were required to provide personal consent and express their willingness to take part in the research.

Research tools

Attitude towards social harms questionnaire (ATSH): This questionnaire is a self-administered questionnaire that is designed based on the dimensions of social harm identified in the research of Jangi Sangani and Razavi in 2024 [20]. The purpose of the questionnaire questions is to evaluate students’ attitudes towards various social issues, which includes 42 questions with five answer options from completely agree to completely disagree. The scores range from 42 to 210, and higher scores indicate greater awareness of the negative consequences that may arise from social interactions. Social harms in the questionnaire include theft, violence, drug abuse, sexual issues, suicide and running away from home. The reliability of the questionnaire was obtained using Cronbach’s α of 0.85, while the validity of the questionnaire was obtained and confirmed using the average variance (AVE) index of 0.54. Likewise, the factorial of the questions was higher than 0.7 [20].

Social well-being questionnaire (SWQ): In 1998, Keyes developed a SWQ consisting of 33 items, following his theoretical model of social well-being structure [21]. This questionnaire is commonly utilized in social health psychology to assess social well-being levels. The questionnaire includes dimensions such as social prosperity, social cohesion, social participation, social solidarity, and social acceptance. The subscale “social cohesion” comprises items 2, 9, 10, 12, 16, and 21, while “social solidarity” includes items 3, 4, 24, 26, 28, and 32. Items 5, 7, 15, 17, 18, 25, and 30 measure the subscale of “social prosperity”, and items 6, 8, 14, 19, 23, and 31 measure the “social acceptance”. Participants rate these items on a five-point Likert scale ranging from completely agree (5) to completely disagree (1). Scores on the questionnaire can range from 33 to 165, with a cutoff score of 82.5.

Higher scores indicate better social health. Keyes conducted two studies involving 373 individuals in the United States to validate his findings, using factor analysis of the 5-dimensional model. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using Cronbach’s α coefficient, which was reported as 0.85 by Keyes and as 0.76 [21, 22]. Likewise, the content validity of the questionnaire in Iran was examined in research in which the scale was translated and then qualitatively confirmed by eight professors of the psychology department. The construct validity of the questionnaire was also calculated based on the correlation coefficients between the subscales and the total score, and the relationship between social well-being and the dimensions of social solidarity, social cohesion, social participation, social flourishing, and social acceptance was found to be 0.707, 0.608, 0.753, 0.771, and 0.737, respectively [23]. At the same time, the reliability of the questionnaire using Cronbach’s α coefficient in the present study was equal to 0.71.

Statistical analysis

The survey questionnaire data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Descriptive analysis included frequencies, percentages, and measures of central tendency and dispersion (Mean±SD). Inferential analysis involved Shapiro’s test for normality, Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances, and repeated measures analysis of covariance. The results were presented according to the group-by-time interaction. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 28.

Results

The Mean±SD age of study participants was 16.2±1.27 years. In terms of the number of family children, 40% of participants in the experimental group and 47% in the control group were the only child in their family. There was no significant difference in the number of siblings (P=0.75) and parental education between the two groups (P=0.87). Table 2 shows the Mean±SD of research outcomes between the two groups at three stages of the study.

The pre-test values of both variables were not significantly different between the two groups. The mean scores of social harms in the experimental group decreased in the post-test and Follow-up stages compared to baseline while these values were similar in the control group in all 3 stages.

According to the findings from the repeated measure covariance analysis presented in Table 3, attitude toward social harm demonstrated a significant group-by-time interaction (F=22.98, P<0.001, η2=0.46), Consequently, separate pairwise analysis were conducted.

The experimental group showed a significant decrease in social harm score at both the post-test and follow-up stage compared to the pre-test (P<0.05). In contrast, the control group didn’t exhibit any significance over time. Similarly, there was a significant group-by-time interaction (F=29.97, P<0.001, η2=0.53) in social health with the experimental group indicating significantly improvement in social health over time (9.37; 95% CI, 7.78%, 11.67%), while the control group did not show a significant change over time (-1.26; 95% CI, -2.85 %, 0.32%). The between-group mean difference in social harm scores from pre-test to post-test was -5.695 (95% CI, -7.81%, -3.57%), indicating a statistically significant reduction in the experimental group compared to the control group. Greater between-group reduction was also found from baseline to follow-up -11.676 (-13.88% to -9.46%). The between-group mean difference in social health scores from pre-test to post-test was 3.551 (95% CI, 1.23% to 5.87%), indicating a statistically significant improvement in the experimental group compared to the control group. A higher between-group improvement was reported from baseline to follow-up 11.14 (95% CI, 9.66% to 12.62%).

Discussion

The primary objective of the current study was to assess the impact of emotional schema therapy on social health and attitudes towards social issues among teenage girls attending conservatories in Shahin Shahr. Emotional schema therapy was found to have a positive effect on the social health of adolescent girls enrolled in conservatories in Shahin Shahr. These findings are in line with previous research conducted by Ataei et al. (2024), Azizi and Saffarinia (2018), and Tashke et al. [17, 24, 25]. The results from studies by Vermziari et al. (2021), Morwaridi et al. (2018), and Penny and Norton (2022) also indicated that schema therapy can enhance social health in individuals with personality disorders or depression [26-28]. Schemas are established and long-lasting structures that develop because of unmet emotional needs during childhood. These schemas are abstract representations of key features of an event that influence an individual’s thoughts, emotions, and behaviors in future intimate relationships and other areas of their lives. They are constructed based on real-life experiences to help individuals make sense of their encounters. Through the utilization of cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques, attachment theory, and Gestalt therapy relationship analysis, a new therapeutic model has been introduced for addressing personality disorders and chronic conditions. Schemas are flawed emotional and cognitive patterns that originate in childhood and persist throughout one’s life. Many of the behaviors exhibited by individuals today stem from difficulties faced during childhood and adolescence. The school of constructivism emerged because of the challenges in effectively treating psychological issues like personality disorders. The history of psychotherapy reveals the complexities involved in treating individuals with personality disorders, making it essential for therapists to employ this treatment approach [17].

The findings suggest that schema therapy effectively reduces the impact of schemas across all areas, leading to a significant improvement in social well-being and enhancement in social adjustment. Schemas are fundamental in the development of psychological issues, disorders, and dysfunctional behaviors in individuals, believed to be ineffective and self-sustaining. They compel individuals to act inconsistently based on distorted perceptions that persist throughout their lives. Schema therapy is thought to address various types of schemas, resulting in the amelioration of psychological issues like social alienation and disrupted interpersonal connections. Unhealthy self-perceptions and negative self-images are exacerbated by schemas, diminishing social engagement, solidarity, and acceptance [28]. Incompatible schemas foster social exclusion and the breakdown of familial and societal support systems, instigating negative self-perceptions that lower social well-being. Schemas contribute significantly to heightened stress, anxiety, and pessimistic thoughts, impacting the physical, mental, and social well-being of individuals. Schemas can be viewed as cognitive structures that store generalized concepts or a structured repository of information, beliefs, and assumptions that mitigate concerns related to negative beliefs and self-criticism, therefore enhancing social health [26, 27].

The research results indicate that emotional schema therapy has an impact on the attitudes towards social harms (such as theft, aggression, drugs, sexual issues, suicide, and running away from home) of teenage girls attending conservatories in Shahin Shahr City. These findings are consistent with the research conducted by Sedaghati and Saraei, as well as Karatzias et al. (2016), Sedaghati Rad et al. (2021), and Dadomo et al. (2018) [15, 29, 30]. Another study by Ghaderi et al. (2016) explored the effects of group schema therapy on the cognitive emotion regulation strategies of students, demonstrating that schema therapy influences cognitive emotion regulation strategies like aggression, self-blame, blame of others, positive reappraisal, catastrophizing, rumination, and effective planning refocusing [31]. The results of this study align with previous research by Dadomo et al. (2018) and Bär et al (2023), which highlight the effectiveness of schema therapy on aggression [29, 32]. Schemas tend to bias human interpretations of events, leading to misunderstandings, distorted attitudes, false assumptions, and unrealistic expectations that reinforce schemas by emphasizing data that supports them while ignoring or downplaying conflicting information. Individuals displaying signs of aggression often possess a schema mindset that triggers aggressive behavior without considering potential consequences, becoming highly sensitive in certain situations that activate these schemas and provoke disturbing emotions, avoidance responses, or harmful actions. This therapeutic approach aims to help individuals identify their incompatible schema mindset and understand the behaviors that perpetuate their schemas, such as avoidance, submission, and extreme compensation [29, 33].

Schema therapy is effective and efficient as it addresses multiple aspects of a person, including cognitive, experiential, emotional, and behavioral dimensions, providing a framework for change. By focusing on the internalized voice of parents and deep-rooted schemas in the cognitive dimension, schema therapy helps individuals understand the origins of their thoughts and challenges the validity of these schemas, leading to a new perspective on themselves and the world. This therapy also helps identify unhealthy patterns and behaviors, allowing individuals to replace them with healthier alternatives, leading to increased self-awareness and improved interpersonal relationships [29].

Experimental techniques also assist patients in emotional reorganization, self-assessment of new knowledge, interpersonal emotion regulation, and self-relaxation to lay the foundation for schema enhancement. Individuals can utilize these techniques to examine the hypotheses of schemas, stimulate the schemas, and connect them to current issues, thereby facilitating emotional insight and subsequent schema improvement. The use of mental imagery enables individuals to identify key schemas, comprehend their evolutionary origins, and link these origins to their present lives. Furthermore, it enhances understanding and facilitates the transition from logical thinking to emotional experience [29]. Through multiple discussions, the emergence of primary emotions such as anger creates a platform for emotional release and helps individuals detach from schemas. By employing mental imagery to disrupt patterns, individuals distance themselves from coping mechanisms characterized by extreme avoidance and compensation. Moreover, using the method of writing letters allows individuals the opportunity to assert their rights and acknowledge their emotions. When emotional needs are partially met during treatment, it sets the stage for schema improvement, as incompatible schemas typically arise from unmet emotional needs. Essentially, in the realm of emotions, schema therapy challenges the cognitive-experiential strategies linked to emotional beliefs, enabling individuals to combat their schemas not only at the cognitive level but also on an emotional plane. This technique aids in emotional release by helping individuals recognize their unmet emotional needs that contribute to the development of schemas [30].

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this study, emotional schema therapy has a positive impact on social health among adolescent girls attending conservatories in Shahin Shahr city. By offering schema therapy workshops in schools, there should be an effort to enhance social health to assist individuals in adapting better to challenges. The study results indicate that group schema therapy is effective in altering attitudes toward social issues among female students at Shahin Shahr’s technical and vocational schools.

The results of this research only applied to female students attending Shahin Shahr’s technical and vocational schools, so any projections should be approached with caution and a thorough understanding. Given that the participants were chosen from those easily accessible, there is a possibility that it may not accurately represent the whole population. The use of a questionnaire rather than interviews raises the risk of tracking the responses provided and their potential connection to the study’s goals. Subsequent studies should focus on measuring more impactful variables. It is suggested that the current study be carried out with a larger sample size and across a wider geographic area to provide a more comprehensive insight into how the variables in question are employed. Future studies should include a longer follow-up period, such as 3 or 6 months, for a more detailed examination. Training in schema therapy, combined with cognitive and emotional techniques, is believed to change schemas. Managing emotions and reducing negative feelings such as aggression can improve the psychological well-being and overall quality of life of individuals who undergo this type of therapy. Therefore, it is recommended that the delivery of such services be incorporated into the educational agenda, particularly for female high school students. Given the target population (students) who face various risk factors for substance abuse, the integration of schema therapy as a preventative measure in high schools can be a means to mitigate the rise in substance abuse and other social problems associated with it in this demographic.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The present work obtained ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of the Islamic Azad University, Khomeinishahr Branch, Khomeinishahr, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.KHSH.REC.1402.013).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to sincerely thank all the individuals who participated in this research.

References

- Fiske ST. Social beings: Core motives in social psychology. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2018. [Link]

- Zarei Y, Jadidi H, Ahmadian H. [Development of a causal model of the relationship between the tendency to psychosocial injuries, emotion regulation strategies and psychological toughness with the mediation of communication with school (Persian)]. Politic Sociol Iran. 2022; 16(4):1412-25. [Link]

- Wood D, Crapnell T, Lau L, Bennett A, Lotstein D, Ferris M, et al. Emerging adulthood as a critical stage in the life course. In: Halfon N, Forrest C, Lerner R, Faustman E, editors. Handbook of life course health development. Cham: Springer; 2018. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-47143-3_7]

- Bailey DH, Duncan GJ, Cunha F, Foorman BR, Yeager DS. Persistence and fade-out of educational-intervention effects: Mechanisms and potential solutions. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2020; 21(2):55-97. [DOI:10.1177/1529100620915848] [PMID]

- Soleimanpour S, Geierstanger S, Brindis CD. Adverse childhood experiences and resilience: Addressing the unique needs of adolescents. Acad Pediatr. 2017; 17(7S):S108-14. [DOI:10.1016/j.acap.2017.01.008] [PMID]

- Otu A, Charles CH, Yaya S. Mental health and psychosocial well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: The invisible elephant in the room. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2020; 14:38. [DOI:10.1186/s13033-020-00371-w] [PMID]

- Carbone G. Do new democracies deliver social welfare? Political regimes and health policy in Ghana and Cameroon. Democratization. 2012; 19(2):157-83. [DOI:10.1080/13510347.2011.572618]

- Sullivan M. Sociology and social welfare. London: Routledge; 2018. [DOI:10.4324/9780429468537]

- Carmo MEd, Guizardi FL. The concept of vulnerability and its meanings for public policies in health and social welfare. Public Health J. 2018; 34(3):e00101417. [DOI:10.1590/0102-311x00101417]

- Mousavi Bazaz SM, Madani A, Mousavi Bazaz SM, Zaree F, Abbasi khaddar E. [Prevalence of psychological disorders and its social determinants among high school students in Bashagard, Iran, 2014 (Persian)]. J Prevent Med. 2015; 2(3):40-6. [Link]

- Heidari N, Nasiri FS, Ghanbari S. [The role of innovative organizational environment in organizational resilience mediating by organizational knowledge creation (Case Study: Secondary School Teachers in Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari Province) (Persian)]. Career Organ Couns. 2022; 14(3):57-82. [DOI:10.48308/jcoc.2022.103041]

- Yadav AK. Social movements, social problems and social change. Acad Voices Multidiscip J. 2015; 5:1-4. [Link]

- Leahy RL. Schematic mismatch in the therapeutic relationship: A social-cognitive model. Psychother Aust. 2013; 19(2):68-80. [Link]

- Leahy RL. Contemporary cognitive therapy: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Guilford Publications; 2015. [Link]

- Sedaghati Rad A, Mohammadipoor M, Saraei A. Comparison of the effectiveness of group schema therapy and Education Based on the theory of planned behavior on addiction of student teachers of Farhangian University of Mashhad. J Sabzevar Uni Med Sci. 2021; 28(3):439-47. [Link]

- Omrani SA, Kamran AT, Salehi M, Dehghanipour N, Tarnas Gh. [The effectiveness of emotional schema therapy on the psychological, emotional and social well-being of women in persistent complex bereavement disorder (Persian)]. Mil Psychol. 2022; 13(50):147-65. [Link]

- Ataei M, Pakizeh A, Dehghani Y, Cheraghi F. Comparing the effectiveness of group schema therapy and cognitive bias modification on test anxiety in male students. Int J Sch Health. 2024; 11(2):105-13. [DOI:10.30476/intjsh.2024.101374.1379]

- Kang H. Sample size determination and power analysis using the G* Power software. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2021; 18:17. [DOI:10.3352/jeehp.2021.18.17] [PMID]

- Leahy RL, Tirch D, Napolitano LA. Emotion regulation in psychotherapy: A practitioner’s guide. New York: Guilford Publications; 2011. [Link]

- Jangi Sangani N, Razavi MR. Investigating the relationship between the use of social media, educational decline, and student mental health. Practice Clin Psychol. 2024; 12(2):123-36. [DOI:10.32598/jpcp.12.2.918.2]

- Keyes CL. Social well-being. Soc Psychol Q. 1998; 61(2):121-40. [DOI:10.2307/2787065]

- Shayeghian Z, Amiri P, Vahedi-Notash G, Karimi M, Azizi F. Validity and reliability of the iranian version of the short form social well being scale in a general urban population. Iran J Public Health. 2020; 49(4):820-1. [PMID]

- Saffarinia M, Tadris Tabrizi M, Aliakbari M. [Exploring the validity, relibility of social well-being questionnaire in men and women resident in Tehran city (Persian)]. Q Educ Meas. 2015; 5(18):115-32. [DOI:10.22054/jem.2015.791]

- Saffarinia M, Azizi Z. [The effect of group schema therapy in promoting social well-being and perception of social trust in university students (Persian)]. Psychol Stud. 2019; 15(1):147-64. [DOI:10.22051/psy.2019.20052.1632]

- Tashke M, Davazdahemamy MH, Bazani M, Shahhosseini M, Mostafa T. [The effectiveness of emotional schema therapy on social acceptability and bullying behavior in adolescents with post-traumatic stress disorder (Persian)]. J Health Res. 2017; 4(2):88-95. [Link]

- Alboushoke SF, Safarzadeh S, Hafezi F, Ehteshamzadeh P. The effectiveness of emotional schema therapy in reducing anxiety sensitivity and body checking behaviors in adolescent girls with social anxiety disorder. Womens Health Bull. 2024; 11(4):272-80. [DOI: 10.30476/whb.2024.103485.1302]

- Penney ES, Norton AR. A novel application of the schema therapy mode model for social anxiety disorder: A naturalistic case study. Clin Case Stud. 2022; 21(1):34-47. [DOI:10.1177/15346501211027866]

- Varmzyar AR, Makvandi,B, Seraj-Khorrami N, Moradi-Manesh F, Moradi N. [The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy on the social anxiety, rumination, and psychological well-being of people with depression referred to the integrated health centers: Randomized clinical trial (Persian)]. J Res Rehabil Sci. 2021; 17(1):9-17. [Link]

- Dadomo H, Panzeri M, Caponcello D, Carmelita A, Grecucci A. Schema therapy for emotional dysregulation in personality disorders: A review. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018; 31(1):43-49. [DOI:10.1097/YCO.0000000000000380] [PMID]

- Karatzias T, Jowett S, Begley A, Deas S. Early maladaptive schemas in adult survivors of interpersonal trauma: foundations for a cognitive theory of psychopathology. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2016; 7:30713. [DOI:10.3402/ejpt.v7.30713] [PMID]

- Ghaderi F, Kalantari M, Mehrabi H. [Effectiveness of group schema therapy on early maladaptive schemas modification and reduce of social anxiety disorder symptoms (Persian)]. Clin Psychol Stud. 2016; 6(24):1-28. [DOI: 10.22054/jcps.2016.6512]

- Bär A, Bär HE, Rijkeboer MM, Lobbestael J. Early Maladaptive Schemas and Schema Modes in clinical disorders: A systematic review. Psychol Psychother. 2023; 96(3):716-47.[DOI:10.1111/papt.12465] [PMID]

- Arendt ITP, Gondan M, Juul S, Hastrup LH, Hjorthøj C, Bach B, et al. Schema therapy versus treatment as usual for outpatients with difficult-to-treat depression: Study protocol for a parallel group randomized clinical trial (DEPRE-ST). Trials. 2024; 25(1):266. [DOI:10.1186/s13063-024-08079-9] [PMID]

Article Type: Original Contributions |

Subject:

Health Education and Promotion

Received: 2024/10/6 | Accepted: 2024/12/8 | Published: 2025/01/29

Received: 2024/10/6 | Accepted: 2024/12/8 | Published: 2025/01/29

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |