Volume 10, Issue 2 (4-2025)

CJHR 2025, 10(2): 81-92 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.GUMS.REC.1400.379

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Farrahi H, Bakhshi F, Basiri H, Amini Khodashahri F, Haghdoost Z. Efficacy of Spiritual-religious Interventions in Iranian Adults With Mental Disorders: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. CJHR 2025; 10 (2) :81-92

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-413-en.html

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-413-en.html

Hassan Farrahi1

, Fataneh Bakhshi *2

, Fataneh Bakhshi *2

, Hadi Basiri3

, Hadi Basiri3

, Fatemeh Amini Khodashahri4

, Fatemeh Amini Khodashahri4

, Zeynab Haghdoost5

, Zeynab Haghdoost5

, Fataneh Bakhshi *2

, Fataneh Bakhshi *2

, Hadi Basiri3

, Hadi Basiri3

, Fatemeh Amini Khodashahri4

, Fatemeh Amini Khodashahri4

, Zeynab Haghdoost5

, Zeynab Haghdoost5

1- Kavosh Cognitive Behavior Sciences and Addiction Research Center, Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

2- Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran ,fa.bakhshi88@gmail.com

3- Department of Islamic Studies, School of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

4- Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

5- Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

2- Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran ,

3- Department of Islamic Studies, School of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

4- Department of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

5- Department of Health Education and Health Promotion, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 648 kb]

(363 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (593 Views)

Full-Text: (341 Views)

Introduction

Mental disorders represent one of the most prominent challenges to global public health, raising significant concerns for healthcare systems, professionals, and policymakers and constituting a primary cause of disability and disease-related burden [1]. According to national surveys in Iran, over 21% of adults experience some form of mental disorder during their lifetime, with depressive and anxiety disorders being the most prevalent [2]. These disorders are characterized by notable clinical symptoms, such as alterations in cognition, mood, emotion, and behavior, often resulting in persistent or recurrent distress and impaired daily functioning [3]. The adverse effects of these conditions extend beyond the affected individual, impacting families, friends, and society at large while incurring substantial economic and social costs [4]. This situation underscores the urgent need to develop comprehensive and effective interventions to improve clinical outcomes (e.g. symptom severity reduction) and functional outcomes (e.g. enhancement of quality of life) for those affected.

Health, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, reflecting its multidimensional nature. Recently, the spiritual dimension of health has emerged as a key factor in promoting well-being and coping with illnesses, particularly mental disorders [5]. In the Iranian context, where cultural norms are deeply intertwined with religious and spiritual beliefs, this dimension may play a pivotal role in supporting individuals with psychological challenges [6].

Spirituality, often overlapping with religiosity, is defined as a force that enables individuals to find meaning and purpose in life and adapt to existential challenges and disease-related stress [7]. Spiritual well-being comprises two facets: Religious well-being, which pertains to satisfaction derived from a connection with a transcendent power (e.g. God in the Islamic tradition), and existential well-being, which focuses on the pursuit of identity and life purpose [5]. Both aspects can serve as resources for resilience and recovery, particularly during psychological crises [8]. In Iran, where the majority of the population adheres to Islam, spiritual-religious care-based interventions, grounded in religious and cultural beliefs, may offer an effective approach to reducing psychological symptoms and enhancing quality of life [9]. These interventions encompass a wide range of activities, including prayer, religious rituals, spiritual counseling, and belief-based therapeutic programs [10].

Recent research has demonstrated that spiritual-religious interventions can positively impact clinical and functional outcomes in individuals with mental disorders. For instance, Moritz et al. reported that a spirituality teaching program for patients with severe depression reduced anxiety and negative thoughts while increasing calmness and self-confidence [11]. Similarly, Gholami and Bashildeh confirmed the effectiveness of spiritual therapy on the mental health of divorced women [12], and Fallahikhoshknab and Ghazanfari found that spiritual activities, such as poetry therapy and pilgrimage, positively influenced the psychological state of schizophrenia patients [13]. Additionally, evidence suggests that these interventions are effective in improving treatment outcomes for substance use disorders [14]. These findings highlight the importance of addressing patients’ spiritual needs, particularly in contexts where spiritual distress is recognized as a clinical diagnosis [15].

Despite growing interest in spiritual-religious interventions in mental health, the diversity in study methodologies and inconsistent findings have hindered precise evaluations of their effectiveness. While some studies have reported significant effects on reducing psychological symptoms and improving functioning [16], others, such as McCullough and Larson, suggest that these effects may be limited in certain subgroups [17]. Such discrepancies may stem from cultural differences, intervention types, or methodological limitations [18]. In Iran, with its unique cultural and religious context, numerous studies have explored these interventions; however, many lack the rigor of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or employ heterogeneous protocols [19]. This underscores the need for systematic reviews to consolidate findings and provide reliable evidence [20].

RCTs are regarded as the gold standard for assessing intervention efficacy [20]. Although previous reviews in Iran have addressed various aspects of spiritual interventions, they often encompass a broad range of study designs, including observational and qualitative studies [21]. While valuable, this breadth fails to provide a clear picture of the effectiveness of spiritual-religious interventions within the RCT framework [22]. The present study, by focusing on RCTs conducted among Iranian adults with mental disorders, seeks to address this gap. Specifically, it examines interventions delivered independently or in combination with other therapeutic approaches that influence clinical and functional outcomes [23]. The objective is to systematically summarize existing evidence and delineate the strengths and limitations of these interventions [24].

The need for such a study in Iran is increasingly evident, given the rising prevalence of mental disorders and the growing acceptance of spiritual-religious interventions [25]. In recent years, Iranian researchers have conducted numerous studies in this field, reflecting heightened attention to spirituality’s role in mental health. For example, Faraji et al. confirmed the efficacy of group poetry therapy in alleviating depression among the elderly [26], while Hosseini et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of a spiritual-religious care model in reducing preoperative anxiety [16]. Nevertheless, the absence of a comprehensive review focusing solely on RCTs has precluded definitive conclusions [27]. This study aims to offer an integrated, evidence-based perspective to assist clinicians and researchers in designing more effective interventions and standardizing protocols [28]. Furthermore, its findings may enrich the international literature on spiritual-religious interventions [29]. Ultimately, this systematic review not only clarifies the role of these interventions in treating mental disorders in Iran but also inspires future research to develop evidence-based protocols [30].

Materials and Methods

This study was a systematic review. A search was conducted across international databases, including Google Scholar, PubMed, ISI Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO, and ClinicalTrials.gov for English-language articles, as well as Iranian databases such as Scientific Information Database (SID), Magiran, Cochrane Iran, Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT), and IranMedx for Persian-language articles. References cited in the included studies were also reviewed. The search spanned from January 2000 to August 2022. Search terms for international databases included: (Spiritual OR religious OR holistic [Title/Abstract]) AND (intervention OR treatment OR therapy OR assistance OR care [Title/Abstract]) AND (clinical trial OR randomized controlled trial OR controlled clinical trial [Title/Abstract]) AND Iran [Title/Abstract]. By spiritual-religious care-based interventions, we mean utilizing concepts, rituals, and recommendations found in spirituality and religion, which are generally focused on God or a higher power, to influence patients’ needs in the illness and treatment process [20]. Although these interventions can vary greatly in terms of spiritual-religious approaches and cultural differences, many commonalities can also be found among them [20].

All titles and abstracts of retrieved articles were imported into EndNote software, where duplicates were removed. Two primary researchers independently screened the titles and abstracts to identify relevant studies and exclude irrelevant ones. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were downloaded and independently assessed by the two researchers based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements between the researchers were resolved through discussion and negotiation. Inclusion criteria comprised articles utilizing spiritual-religious care-based interventions, RCTs meeting all three clinical trial criteria (randomization, control group, and intervention group), studies involving patients with mental disorders, and studies with participants aged 18 years and older. Exclusion criteria included: Non-original research reports (e.g. organizational reports or reviews), articles in languages other than English or Persian, studies examining mindfulness-based interventions, and studies assessing intervention effectiveness in non-patient populations.

The 11-item Cochrane back review scale, as a quality rating standard, was used to evaluate the quality of the articles. According to the proposed rule, articles that meet at least 6 out of the 11 validity criteria are included in the review [31]. Each item was scored as follows: + if present in the article, - if absent, and ? if uncertainty existed regarding its presence (I don’t know). Data extracted for reporting study results included: Author (year), participants, age range and gender, sample size, scale, type of intervention, follow-up duration, trial location, and results.

Results

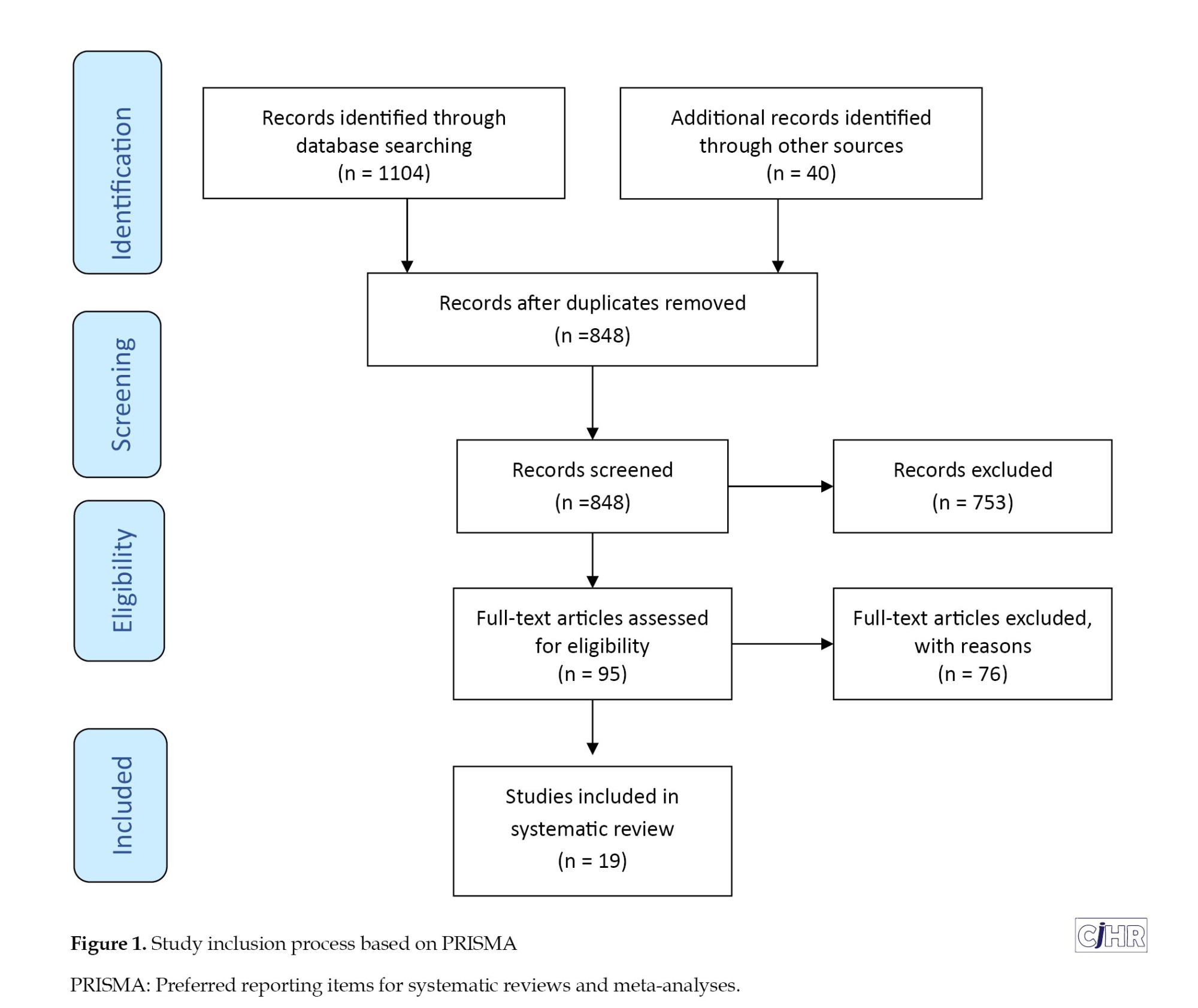

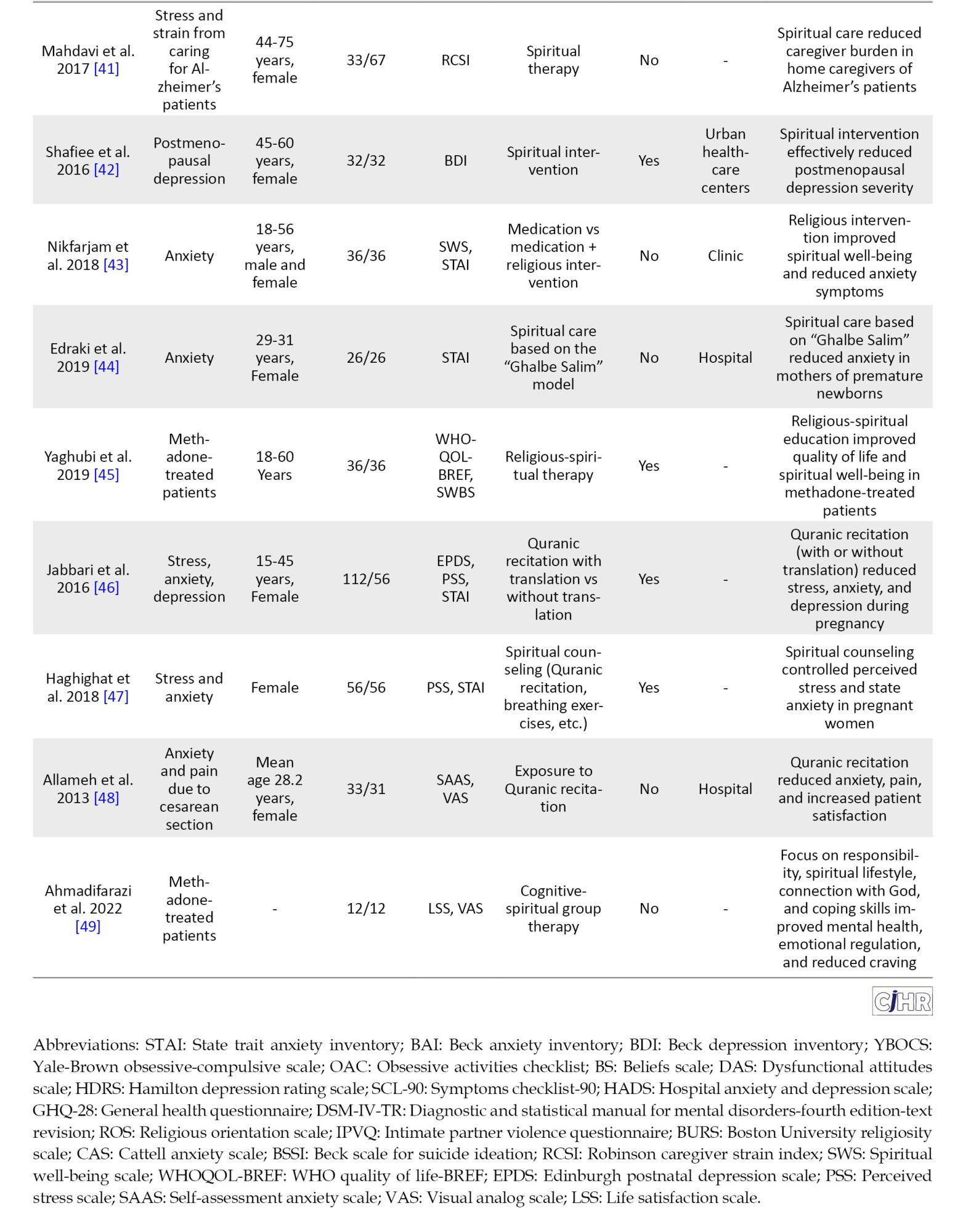

A total of 1144 studies were identified in scientific journals across the databases. Of these, 296 were excluded in the first stage (duplicates), 753 in the second stage (after abstract screening due to language or irrelevance), and 76 in the third stage (after full-text screening due to non-Persian authorship or topical mismatch). Ultimately, 10 Persian-language and 9 English-language studies remained. The selection and review process, based on preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA), is illustrated in Figure 1.

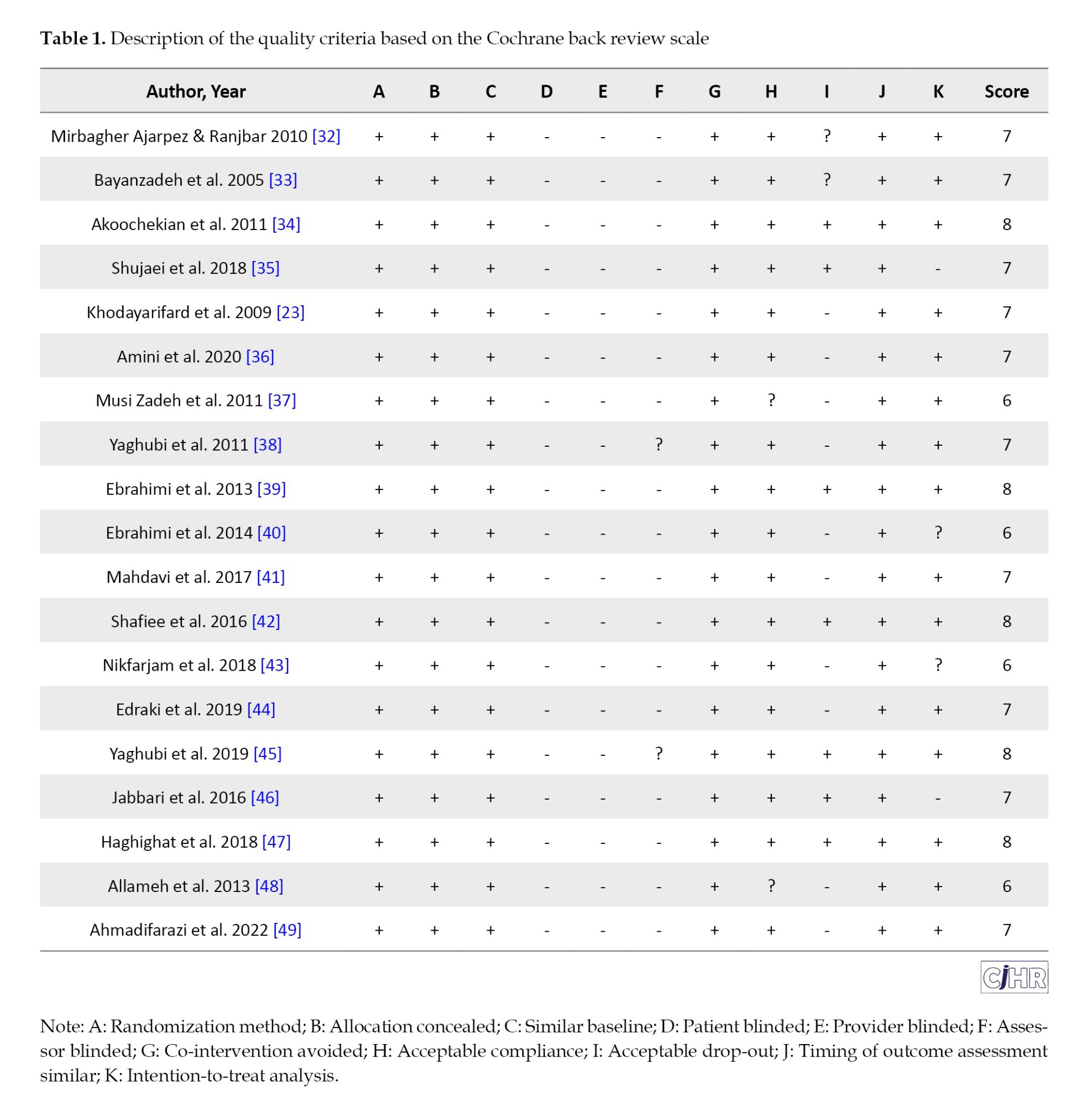

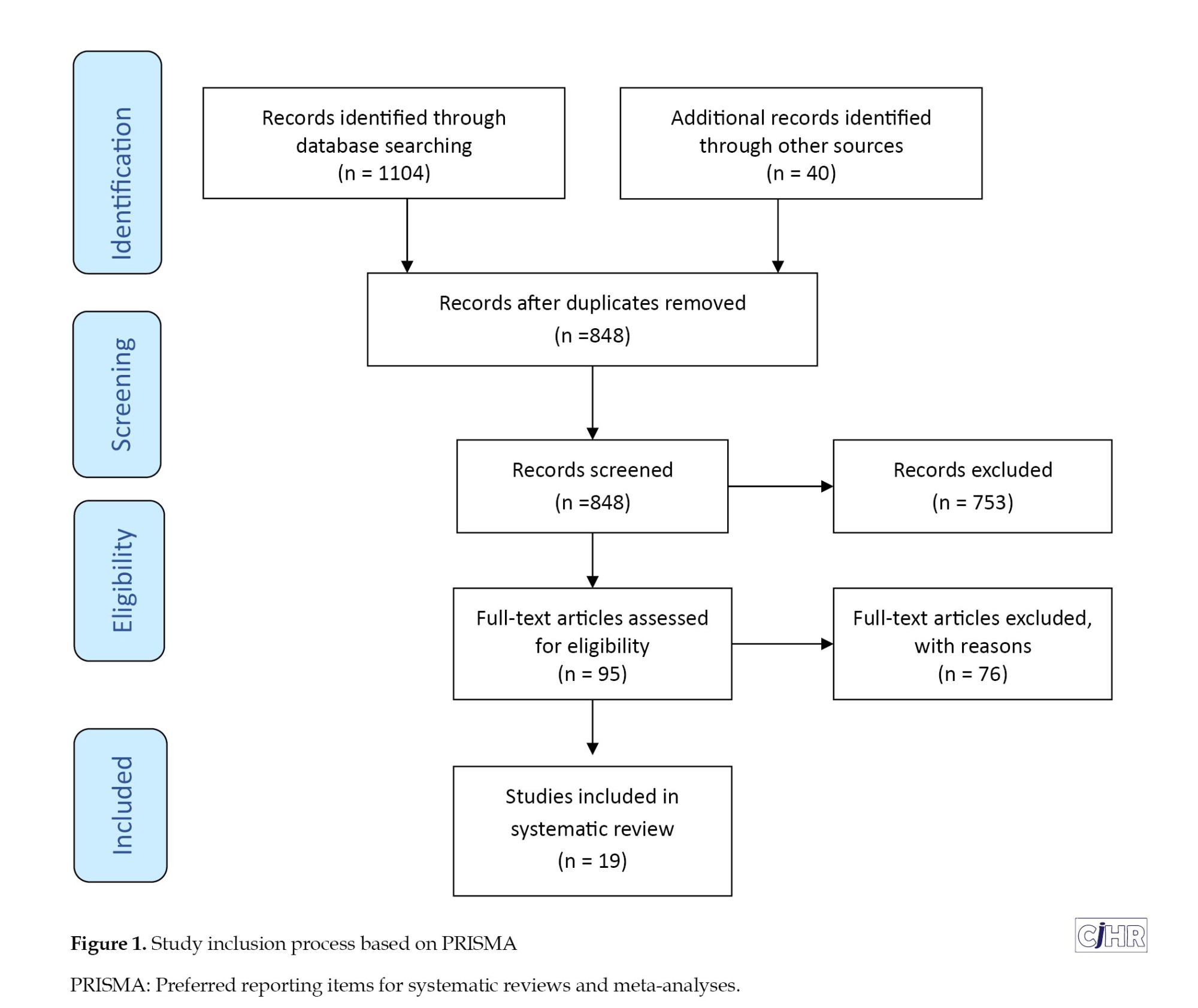

Table 1 presents the quality assessment of the 19 selected studies evaluated using the Cochrane back review scale. All items in the Cochrane back review scale were assessed, and the accepted studies met at least six out of 11 validity criteria [31].

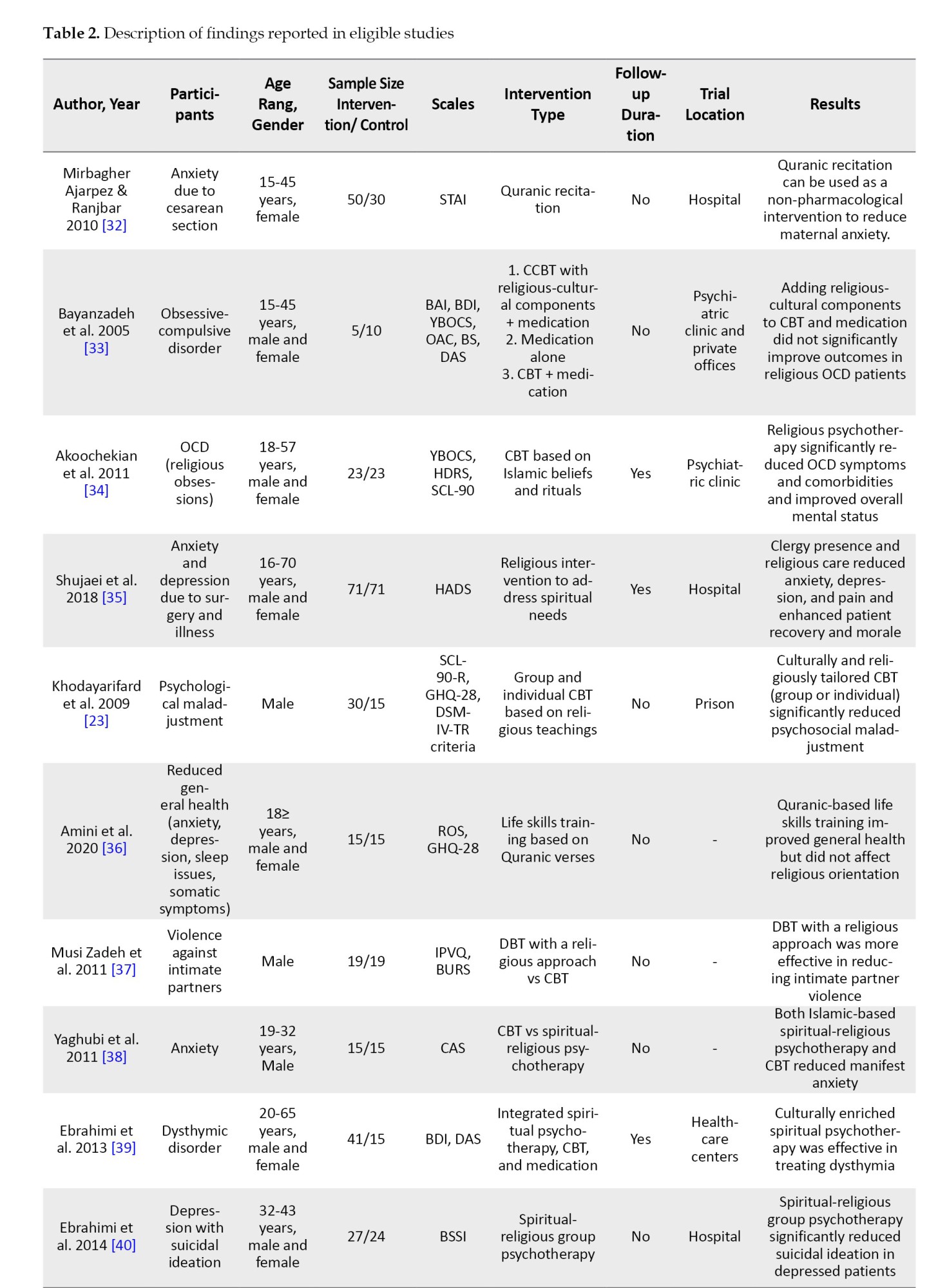

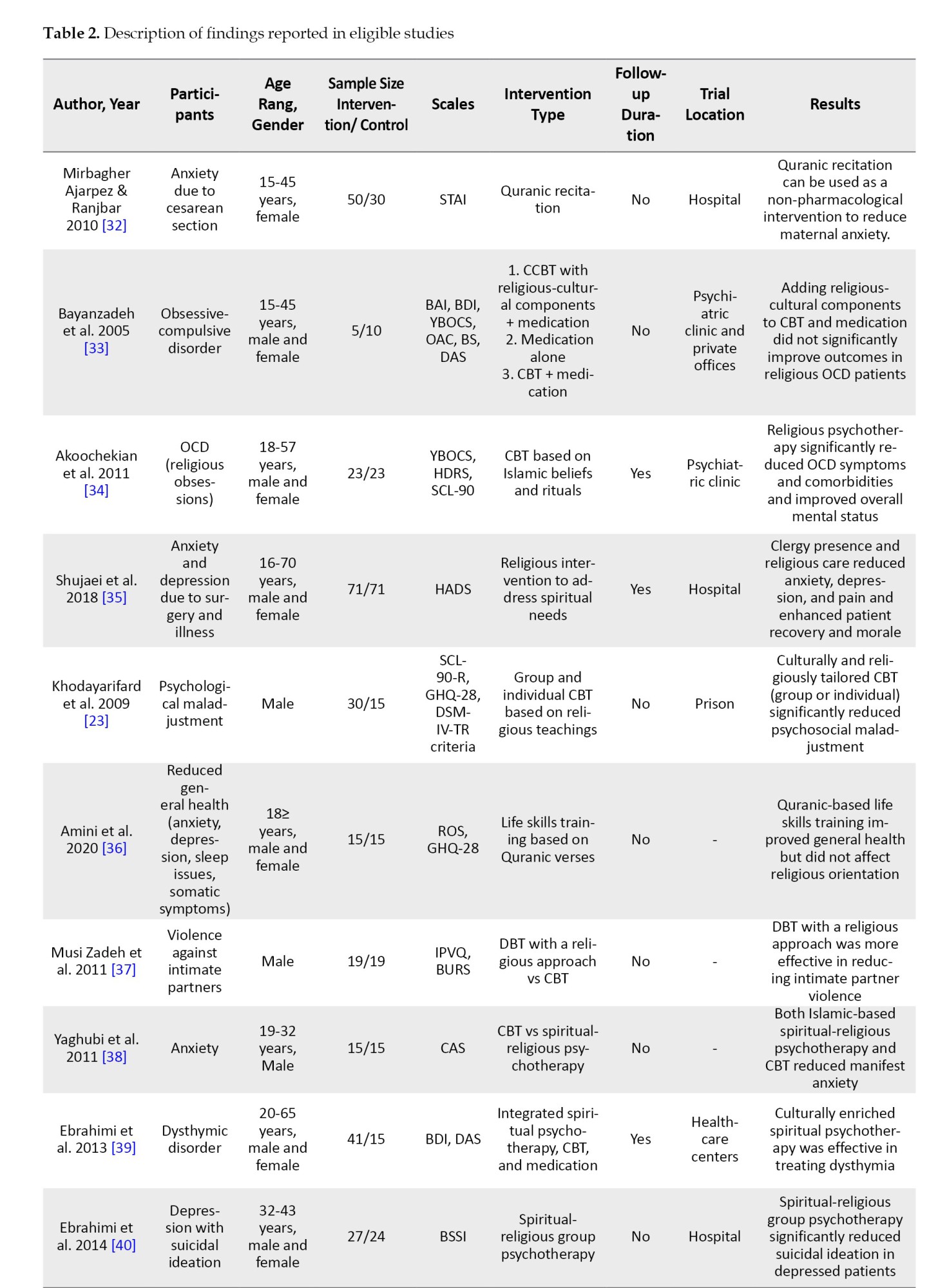

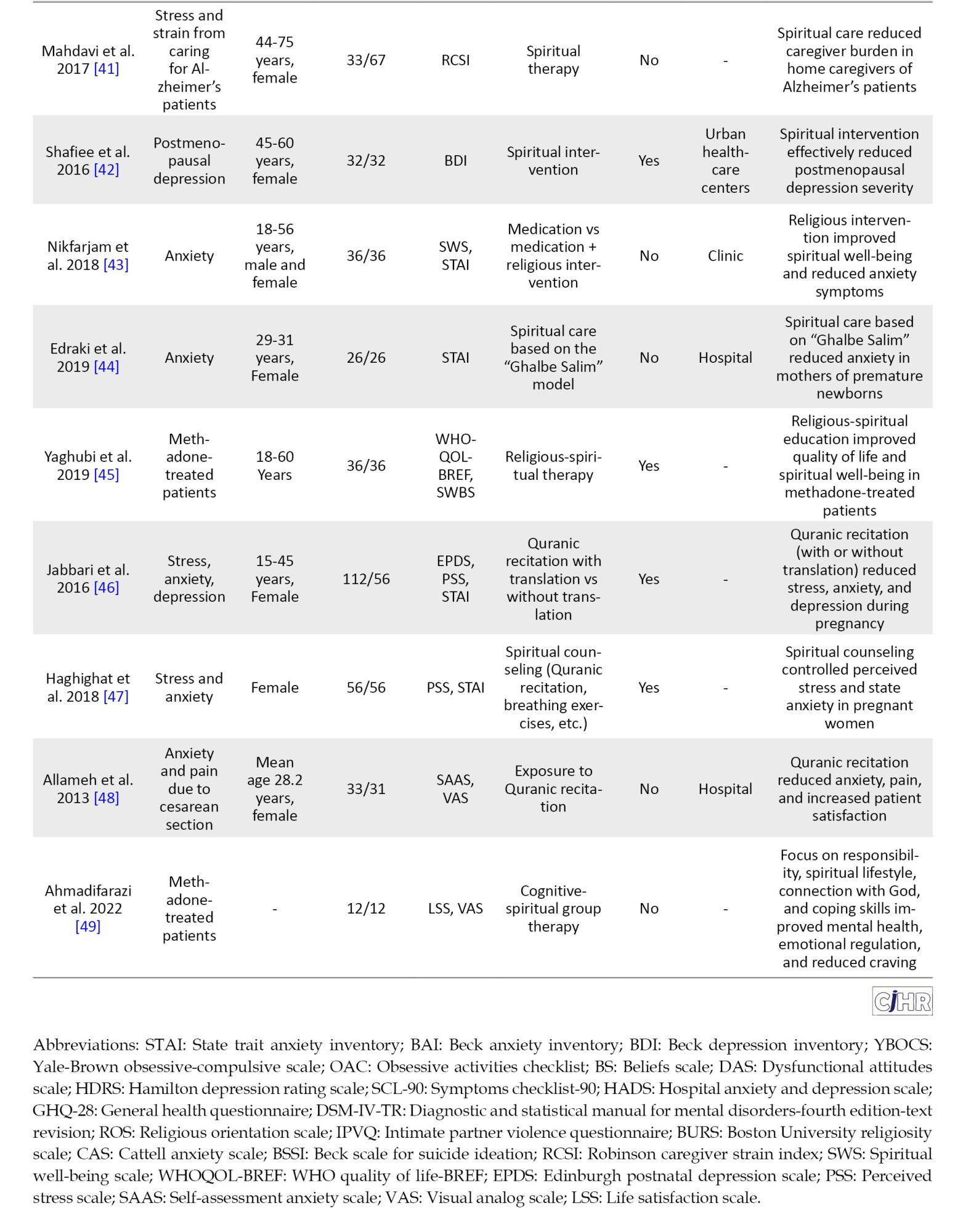

The general characteristics of the selected studies are presented in Table 2. The target populations included patients or individuals with mental disorders or negative psychological symptoms, as well as healthy individuals. A total of 1284 patients and controls across 19 studies were examined [24, 32-49]. Diagnoses or negative psychological symptoms spanned a wide range, including anxiety, stress, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, psychological maladjustment, reduced general health, violence against intimate partners, and caregiver burden from caring for Alzheimer’s patients. In some studies, the target population comprised patients with mental disorders, while in most, it included individuals exhibiting varying degrees of negative psychological symptoms, such as anxiety and depression. Collectively, all studies focused on groups experiencing psychological challenges. Study outcomes emphasized constructs such as hope, mental health, spiritual well-being, quality of life, resilience, anxiety, obsession, addiction, violence, distress, and depression, with less attention given to physical health dimensions. Therapeutic interventions were conducted in healthcare centers, hospitals, and clinics in all studies, except for one conducted in a prison setting [24].

Table 2 indicates that the authors employed a variety of protocols to implement spiritual-religious interventions. Overall, these protocols can be categorized into two groups: (a) Independent spiritual-religious interventions and (b) Spiritual-religious interventions combined with conventional psychological interventions, particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT). The spiritual-religious interventions within both categories were highly diverse, ranging from listening to Quranic recitations to training in life skills based on the Quran. These interventions were conducted both individually and in group settings. It is noteworthy that many studies utilized their innovative protocols, while some adopted previously established models, notably the “Ghalbe Salim” (Sound Heart) model. All reviewed studies did not establish a clear distinction between spiritual and religious interventions; thus, delineating boundaries between these two types of interventions and their respective protocols is not feasible in this study. It appears that all or most of these studies incorporated some form of attention to or practice of religious teachings within their interventions. Pharmacological treatments were administered by psychiatrists, and spiritual, religious, and faith-based interventions were delivered by specialized clergy, clinical psychologists, and nurses, while behavioral and cognitive-behavioral therapies were conducted by clinical psychologists. Of these studies, eight were implemented in group formats, with the remainder conducted individually. Follow-up after treatment was reported in only eight studies.

Discussion

This systematic review synthesized evidence from 19 RCTs examining the effectiveness of spiritual-religious interventions on clinical and functional outcomes among Iranian adults with mental disorders or related psychological distress [32-49]. The findings indicated a generally positive impact across a range of conditions, including anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), substance use-related issues, and psychological distress associated with caregiving or medical procedures. These results align with the growing global literature suggesting that S/R interventions can enhance mental health outcomes by addressing existential and psychological needs [20, 25]. However, the heterogeneity in intervention types, study populations, and outcome measures warrants a nuanced interpretation of their efficacy and applicability in clinical practice.

A predominant finding across the reviewed studies is the significant reduction in anxiety symptoms following S/R interventions. Trials such as those by Mirbagher Ajarpez and Ranjbar [32], Allameh et al. [49], and Edraki et al. [44] demonstrated that interventions like Quranic recitation or spiritually integrated counseling substantially lowered anxiety in women undergoing cesarean sections or caring for premature newborns. Similarly, Nikfarjam et al. [43] and Yaghubi et al. [38] reported reduced anxiety in diverse populations, including methadone-treated patients, through religious-spiritual group therapy. These outcomes resonate with previous research indicating that spiritual practices, such as prayer or connection to a transcendent entity, can mitigate anxiety by fostering a sense of calm and hope [7, 11]. The cultural resonance of Islamic practices in Iran likely amplifies this effect, as suggested by the effectiveness of interventions rooted in Quranic teachings or Islamic models like “Ghalbe Salim” [45].

Depression, another prevalent condition in the reviewed studies, also showed improvement with S/R interventions. Studies by Shafiee et al. [42], Ebrahimi et al. [39, 40], and Jabbari et al. [46] reported significant reductions in depressive symptoms among postmenopausal women, patients with dysthymia, and pregnant women, respectively, using interventions ranging from spiritual group therapy to Quranic recitation with translation. These findings corroborate meta-analyses that highlight the efficacy of spiritually integrated psychotherapy in alleviating depression by enhancing self-compassion and reducing negative cognitions [23, 25]. Notably, the study by Ebrahimi et al. [40] also found a decrease in suicidal ideation, suggesting that S/R interventions may address severe manifestations of depression, potentially through fostering meaning and purpose—key components of spiritual well-being [8].

The effectiveness of S/R interventions extends beyond common mental disorders to specific conditions like OCD and substance use disorders. Akoochekian et al. [34] demonstrated that religiously tailored CBT significantly reduced OCD symptoms with religious content, a finding consistent with the notion that culturally adapted therapies enhance treatment relevance and efficacy [6, 10]. Conversely, Bayanzadeh et al. [33] found no added benefit from incorporating religious-cultural elements into CBT for OCD, highlighting potential variability in response based on intervention design or patient religiosity. For substance use, Ahmadifarazi et al. [49] and Yaghubi et al. [45] reported improved mental health, craving reduction, and quality of life in methadone-treated patients following spiritually integrated group therapy, aligning with global evidence on the role of spirituality in addiction recovery [14]. These mixed results underscore the need for standardized protocols to clarify the conditions under which S/R interventions yield optimal benefits.

Functional outcomes, such as quality of life and caregiver burden, also improved with S/R interventions in several studies. Yaghubi et al. [45] found enhanced quality of life and spiritual well-being in methadone-treated patients, while Mahdavi et al. [41] reported reduced caregiver strain among women caring for Alzheimer’s patients. These findings suggest that S/R interventions may bolster resilience and social functioning, key aspects of mental health recovery [4, 5]. The mechanisms likely involve the reinforcement of social support and existential coping, which are critical in Iranian contexts where community and religious ties are strong [9]. However, the lack of consistent follow-up across studies limits conclusions about the durability of these functional gains, a gap also noted in broader spiritual intervention research [28].

The cultural and religious context of Iran appears to be a critical factor in the observed efficacy of S/R interventions. Studies leveraging Islamic teachings, such as Quranic recitation or spiritually enriched CBT, consistently reported positive outcomes [32, 34, 39, 47], supporting the hypothesis that culturally congruent interventions enhance therapeutic alliance and patient engagement [6, 16]. This aligns with global evidence indicating that the effectiveness of spiritual interventions is mediated by cultural and religious alignment [18, 30]. However, the lack of significant improvement in some studies [33] suggests that religiosity alone may not suffice without integration into evidence-based frameworks like CBT, a point reinforced by meta-analyses advocating for combined approaches [25, 31]. Future research should explore patient-level factors, such as baseline religiosity, to better tailor these interventions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review provides robust evidence that S/R interventions can effectively improve clinical (e.g. anxiety, depression) and functional (e.g. quality of life, caregiver burden) outcomes in Iranian adults with mental disorders, particularly when aligned with Islamic cultural frameworks. These findings contribute to the global discourse on spiritually integrated care while highlighting the need for larger, standardized RCTs with long-term follow-up to confirm durability and scalability. Clinicians in Iran may consider incorporating S/R elements into practice, especially for religious patients, while researchers should prioritize protocol harmonization and exploration of moderating factors to refine these interventions further. This review underscores the therapeutic potential of spirituality in a culturally unique setting, offering a foundation for evidence-based mental health strategies in Iran.

Limitations

Despite the promising results, several limitations and inconsistencies emerge from the reviewed studies. The variability in intervention modalities—ranging from Quranic recitation to structured psychotherapy—complicates direct comparisons and generalizability. Sample sizes were often small (e.g. 5-15 participants per arm in some trials), potentially reducing statistical power and reliability Additionally, only eight studies included follow-up assessments, leaving the long-term efficacy of S/R interventions uncertain. This echoes broader critiques of spiritual intervention research, where short-term effects are more commonly documented than sustained outcomes. Furthermore, the predominance of female participants in studies targeting perinatal or postmenopausal issues suggests a gender bias that may not reflect the broader Iranian population with mental disorders.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Scientific and Ethical Committees of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1400.379).

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is the review with no human or animal sample. There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this work.

Funding

This research was supported by the research project, funded by Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Grant No.: 1400072620).

Authors' contributions

Methodology: Fataneh Bakhshi, Hassan Farrahi, and Hadi Basiri; Investigation, Data collection, and Data curation: Fataneh Bakhshi, Hassan Farrahi, Fatemeh Amini Khodashahri, and Zeinab Haghdoost; Data analysis: Fataneh Bakhshi, Hassan Farrahi, Fatemeh Amini Khodashahri; Writing the original draft: Fataneh Bakhshi, Hassan Farrahi, Fatemeh Amini Khodashahri; Review and editing: Fataneh Bakhshi and Hassan Farrahi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Mental disorders represent one of the most prominent challenges to global public health, raising significant concerns for healthcare systems, professionals, and policymakers and constituting a primary cause of disability and disease-related burden [1]. According to national surveys in Iran, over 21% of adults experience some form of mental disorder during their lifetime, with depressive and anxiety disorders being the most prevalent [2]. These disorders are characterized by notable clinical symptoms, such as alterations in cognition, mood, emotion, and behavior, often resulting in persistent or recurrent distress and impaired daily functioning [3]. The adverse effects of these conditions extend beyond the affected individual, impacting families, friends, and society at large while incurring substantial economic and social costs [4]. This situation underscores the urgent need to develop comprehensive and effective interventions to improve clinical outcomes (e.g. symptom severity reduction) and functional outcomes (e.g. enhancement of quality of life) for those affected.

Health, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, reflecting its multidimensional nature. Recently, the spiritual dimension of health has emerged as a key factor in promoting well-being and coping with illnesses, particularly mental disorders [5]. In the Iranian context, where cultural norms are deeply intertwined with religious and spiritual beliefs, this dimension may play a pivotal role in supporting individuals with psychological challenges [6].

Spirituality, often overlapping with religiosity, is defined as a force that enables individuals to find meaning and purpose in life and adapt to existential challenges and disease-related stress [7]. Spiritual well-being comprises two facets: Religious well-being, which pertains to satisfaction derived from a connection with a transcendent power (e.g. God in the Islamic tradition), and existential well-being, which focuses on the pursuit of identity and life purpose [5]. Both aspects can serve as resources for resilience and recovery, particularly during psychological crises [8]. In Iran, where the majority of the population adheres to Islam, spiritual-religious care-based interventions, grounded in religious and cultural beliefs, may offer an effective approach to reducing psychological symptoms and enhancing quality of life [9]. These interventions encompass a wide range of activities, including prayer, religious rituals, spiritual counseling, and belief-based therapeutic programs [10].

Recent research has demonstrated that spiritual-religious interventions can positively impact clinical and functional outcomes in individuals with mental disorders. For instance, Moritz et al. reported that a spirituality teaching program for patients with severe depression reduced anxiety and negative thoughts while increasing calmness and self-confidence [11]. Similarly, Gholami and Bashildeh confirmed the effectiveness of spiritual therapy on the mental health of divorced women [12], and Fallahikhoshknab and Ghazanfari found that spiritual activities, such as poetry therapy and pilgrimage, positively influenced the psychological state of schizophrenia patients [13]. Additionally, evidence suggests that these interventions are effective in improving treatment outcomes for substance use disorders [14]. These findings highlight the importance of addressing patients’ spiritual needs, particularly in contexts where spiritual distress is recognized as a clinical diagnosis [15].

Despite growing interest in spiritual-religious interventions in mental health, the diversity in study methodologies and inconsistent findings have hindered precise evaluations of their effectiveness. While some studies have reported significant effects on reducing psychological symptoms and improving functioning [16], others, such as McCullough and Larson, suggest that these effects may be limited in certain subgroups [17]. Such discrepancies may stem from cultural differences, intervention types, or methodological limitations [18]. In Iran, with its unique cultural and religious context, numerous studies have explored these interventions; however, many lack the rigor of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or employ heterogeneous protocols [19]. This underscores the need for systematic reviews to consolidate findings and provide reliable evidence [20].

RCTs are regarded as the gold standard for assessing intervention efficacy [20]. Although previous reviews in Iran have addressed various aspects of spiritual interventions, they often encompass a broad range of study designs, including observational and qualitative studies [21]. While valuable, this breadth fails to provide a clear picture of the effectiveness of spiritual-religious interventions within the RCT framework [22]. The present study, by focusing on RCTs conducted among Iranian adults with mental disorders, seeks to address this gap. Specifically, it examines interventions delivered independently or in combination with other therapeutic approaches that influence clinical and functional outcomes [23]. The objective is to systematically summarize existing evidence and delineate the strengths and limitations of these interventions [24].

The need for such a study in Iran is increasingly evident, given the rising prevalence of mental disorders and the growing acceptance of spiritual-religious interventions [25]. In recent years, Iranian researchers have conducted numerous studies in this field, reflecting heightened attention to spirituality’s role in mental health. For example, Faraji et al. confirmed the efficacy of group poetry therapy in alleviating depression among the elderly [26], while Hosseini et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of a spiritual-religious care model in reducing preoperative anxiety [16]. Nevertheless, the absence of a comprehensive review focusing solely on RCTs has precluded definitive conclusions [27]. This study aims to offer an integrated, evidence-based perspective to assist clinicians and researchers in designing more effective interventions and standardizing protocols [28]. Furthermore, its findings may enrich the international literature on spiritual-religious interventions [29]. Ultimately, this systematic review not only clarifies the role of these interventions in treating mental disorders in Iran but also inspires future research to develop evidence-based protocols [30].

Materials and Methods

This study was a systematic review. A search was conducted across international databases, including Google Scholar, PubMed, ISI Web of Science, Scopus, PsycINFO, and ClinicalTrials.gov for English-language articles, as well as Iranian databases such as Scientific Information Database (SID), Magiran, Cochrane Iran, Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT), and IranMedx for Persian-language articles. References cited in the included studies were also reviewed. The search spanned from January 2000 to August 2022. Search terms for international databases included: (Spiritual OR religious OR holistic [Title/Abstract]) AND (intervention OR treatment OR therapy OR assistance OR care [Title/Abstract]) AND (clinical trial OR randomized controlled trial OR controlled clinical trial [Title/Abstract]) AND Iran [Title/Abstract]. By spiritual-religious care-based interventions, we mean utilizing concepts, rituals, and recommendations found in spirituality and religion, which are generally focused on God or a higher power, to influence patients’ needs in the illness and treatment process [20]. Although these interventions can vary greatly in terms of spiritual-religious approaches and cultural differences, many commonalities can also be found among them [20].

All titles and abstracts of retrieved articles were imported into EndNote software, where duplicates were removed. Two primary researchers independently screened the titles and abstracts to identify relevant studies and exclude irrelevant ones. Full texts of potentially relevant articles were downloaded and independently assessed by the two researchers based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements between the researchers were resolved through discussion and negotiation. Inclusion criteria comprised articles utilizing spiritual-religious care-based interventions, RCTs meeting all three clinical trial criteria (randomization, control group, and intervention group), studies involving patients with mental disorders, and studies with participants aged 18 years and older. Exclusion criteria included: Non-original research reports (e.g. organizational reports or reviews), articles in languages other than English or Persian, studies examining mindfulness-based interventions, and studies assessing intervention effectiveness in non-patient populations.

The 11-item Cochrane back review scale, as a quality rating standard, was used to evaluate the quality of the articles. According to the proposed rule, articles that meet at least 6 out of the 11 validity criteria are included in the review [31]. Each item was scored as follows: + if present in the article, - if absent, and ? if uncertainty existed regarding its presence (I don’t know). Data extracted for reporting study results included: Author (year), participants, age range and gender, sample size, scale, type of intervention, follow-up duration, trial location, and results.

Results

A total of 1144 studies were identified in scientific journals across the databases. Of these, 296 were excluded in the first stage (duplicates), 753 in the second stage (after abstract screening due to language or irrelevance), and 76 in the third stage (after full-text screening due to non-Persian authorship or topical mismatch). Ultimately, 10 Persian-language and 9 English-language studies remained. The selection and review process, based on preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA), is illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1 presents the quality assessment of the 19 selected studies evaluated using the Cochrane back review scale. All items in the Cochrane back review scale were assessed, and the accepted studies met at least six out of 11 validity criteria [31].

The general characteristics of the selected studies are presented in Table 2. The target populations included patients or individuals with mental disorders or negative psychological symptoms, as well as healthy individuals. A total of 1284 patients and controls across 19 studies were examined [24, 32-49]. Diagnoses or negative psychological symptoms spanned a wide range, including anxiety, stress, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, psychological maladjustment, reduced general health, violence against intimate partners, and caregiver burden from caring for Alzheimer’s patients. In some studies, the target population comprised patients with mental disorders, while in most, it included individuals exhibiting varying degrees of negative psychological symptoms, such as anxiety and depression. Collectively, all studies focused on groups experiencing psychological challenges. Study outcomes emphasized constructs such as hope, mental health, spiritual well-being, quality of life, resilience, anxiety, obsession, addiction, violence, distress, and depression, with less attention given to physical health dimensions. Therapeutic interventions were conducted in healthcare centers, hospitals, and clinics in all studies, except for one conducted in a prison setting [24].

Table 2 indicates that the authors employed a variety of protocols to implement spiritual-religious interventions. Overall, these protocols can be categorized into two groups: (a) Independent spiritual-religious interventions and (b) Spiritual-religious interventions combined with conventional psychological interventions, particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT). The spiritual-religious interventions within both categories were highly diverse, ranging from listening to Quranic recitations to training in life skills based on the Quran. These interventions were conducted both individually and in group settings. It is noteworthy that many studies utilized their innovative protocols, while some adopted previously established models, notably the “Ghalbe Salim” (Sound Heart) model. All reviewed studies did not establish a clear distinction between spiritual and religious interventions; thus, delineating boundaries between these two types of interventions and their respective protocols is not feasible in this study. It appears that all or most of these studies incorporated some form of attention to or practice of religious teachings within their interventions. Pharmacological treatments were administered by psychiatrists, and spiritual, religious, and faith-based interventions were delivered by specialized clergy, clinical psychologists, and nurses, while behavioral and cognitive-behavioral therapies were conducted by clinical psychologists. Of these studies, eight were implemented in group formats, with the remainder conducted individually. Follow-up after treatment was reported in only eight studies.

Discussion

This systematic review synthesized evidence from 19 RCTs examining the effectiveness of spiritual-religious interventions on clinical and functional outcomes among Iranian adults with mental disorders or related psychological distress [32-49]. The findings indicated a generally positive impact across a range of conditions, including anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), substance use-related issues, and psychological distress associated with caregiving or medical procedures. These results align with the growing global literature suggesting that S/R interventions can enhance mental health outcomes by addressing existential and psychological needs [20, 25]. However, the heterogeneity in intervention types, study populations, and outcome measures warrants a nuanced interpretation of their efficacy and applicability in clinical practice.

A predominant finding across the reviewed studies is the significant reduction in anxiety symptoms following S/R interventions. Trials such as those by Mirbagher Ajarpez and Ranjbar [32], Allameh et al. [49], and Edraki et al. [44] demonstrated that interventions like Quranic recitation or spiritually integrated counseling substantially lowered anxiety in women undergoing cesarean sections or caring for premature newborns. Similarly, Nikfarjam et al. [43] and Yaghubi et al. [38] reported reduced anxiety in diverse populations, including methadone-treated patients, through religious-spiritual group therapy. These outcomes resonate with previous research indicating that spiritual practices, such as prayer or connection to a transcendent entity, can mitigate anxiety by fostering a sense of calm and hope [7, 11]. The cultural resonance of Islamic practices in Iran likely amplifies this effect, as suggested by the effectiveness of interventions rooted in Quranic teachings or Islamic models like “Ghalbe Salim” [45].

Depression, another prevalent condition in the reviewed studies, also showed improvement with S/R interventions. Studies by Shafiee et al. [42], Ebrahimi et al. [39, 40], and Jabbari et al. [46] reported significant reductions in depressive symptoms among postmenopausal women, patients with dysthymia, and pregnant women, respectively, using interventions ranging from spiritual group therapy to Quranic recitation with translation. These findings corroborate meta-analyses that highlight the efficacy of spiritually integrated psychotherapy in alleviating depression by enhancing self-compassion and reducing negative cognitions [23, 25]. Notably, the study by Ebrahimi et al. [40] also found a decrease in suicidal ideation, suggesting that S/R interventions may address severe manifestations of depression, potentially through fostering meaning and purpose—key components of spiritual well-being [8].

The effectiveness of S/R interventions extends beyond common mental disorders to specific conditions like OCD and substance use disorders. Akoochekian et al. [34] demonstrated that religiously tailored CBT significantly reduced OCD symptoms with religious content, a finding consistent with the notion that culturally adapted therapies enhance treatment relevance and efficacy [6, 10]. Conversely, Bayanzadeh et al. [33] found no added benefit from incorporating religious-cultural elements into CBT for OCD, highlighting potential variability in response based on intervention design or patient religiosity. For substance use, Ahmadifarazi et al. [49] and Yaghubi et al. [45] reported improved mental health, craving reduction, and quality of life in methadone-treated patients following spiritually integrated group therapy, aligning with global evidence on the role of spirituality in addiction recovery [14]. These mixed results underscore the need for standardized protocols to clarify the conditions under which S/R interventions yield optimal benefits.

Functional outcomes, such as quality of life and caregiver burden, also improved with S/R interventions in several studies. Yaghubi et al. [45] found enhanced quality of life and spiritual well-being in methadone-treated patients, while Mahdavi et al. [41] reported reduced caregiver strain among women caring for Alzheimer’s patients. These findings suggest that S/R interventions may bolster resilience and social functioning, key aspects of mental health recovery [4, 5]. The mechanisms likely involve the reinforcement of social support and existential coping, which are critical in Iranian contexts where community and religious ties are strong [9]. However, the lack of consistent follow-up across studies limits conclusions about the durability of these functional gains, a gap also noted in broader spiritual intervention research [28].

The cultural and religious context of Iran appears to be a critical factor in the observed efficacy of S/R interventions. Studies leveraging Islamic teachings, such as Quranic recitation or spiritually enriched CBT, consistently reported positive outcomes [32, 34, 39, 47], supporting the hypothesis that culturally congruent interventions enhance therapeutic alliance and patient engagement [6, 16]. This aligns with global evidence indicating that the effectiveness of spiritual interventions is mediated by cultural and religious alignment [18, 30]. However, the lack of significant improvement in some studies [33] suggests that religiosity alone may not suffice without integration into evidence-based frameworks like CBT, a point reinforced by meta-analyses advocating for combined approaches [25, 31]. Future research should explore patient-level factors, such as baseline religiosity, to better tailor these interventions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review provides robust evidence that S/R interventions can effectively improve clinical (e.g. anxiety, depression) and functional (e.g. quality of life, caregiver burden) outcomes in Iranian adults with mental disorders, particularly when aligned with Islamic cultural frameworks. These findings contribute to the global discourse on spiritually integrated care while highlighting the need for larger, standardized RCTs with long-term follow-up to confirm durability and scalability. Clinicians in Iran may consider incorporating S/R elements into practice, especially for religious patients, while researchers should prioritize protocol harmonization and exploration of moderating factors to refine these interventions further. This review underscores the therapeutic potential of spirituality in a culturally unique setting, offering a foundation for evidence-based mental health strategies in Iran.

Limitations

Despite the promising results, several limitations and inconsistencies emerge from the reviewed studies. The variability in intervention modalities—ranging from Quranic recitation to structured psychotherapy—complicates direct comparisons and generalizability. Sample sizes were often small (e.g. 5-15 participants per arm in some trials), potentially reducing statistical power and reliability Additionally, only eight studies included follow-up assessments, leaving the long-term efficacy of S/R interventions uncertain. This echoes broader critiques of spiritual intervention research, where short-term effects are more commonly documented than sustained outcomes. Furthermore, the predominance of female participants in studies targeting perinatal or postmenopausal issues suggests a gender bias that may not reflect the broader Iranian population with mental disorders.

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Scientific and Ethical Committees of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1400.379).

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is the review with no human or animal sample. There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this work.

Funding

This research was supported by the research project, funded by Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Grant No.: 1400072620).

Authors' contributions

Methodology: Fataneh Bakhshi, Hassan Farrahi, and Hadi Basiri; Investigation, Data collection, and Data curation: Fataneh Bakhshi, Hassan Farrahi, Fatemeh Amini Khodashahri, and Zeinab Haghdoost; Data analysis: Fataneh Bakhshi, Hassan Farrahi, Fatemeh Amini Khodashahri; Writing the original draft: Fataneh Bakhshi, Hassan Farrahi, Fatemeh Amini Khodashahri; Review and editing: Fataneh Bakhshi and Hassan Farrahi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Alonso J, Chatterji S, He Y, editors. The burdens of mental disorders: Global perspectives from the WHO world mental health surveys. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013. [Link]

- Noorbala A. [Psychosocial health and strategies for improvement (Persian)]. Iran J Psychiatr Clin Psychol. 2011; 17(2):151-6. [Link]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). 5th ed. Washington: APA; 2013. [DOI:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596]

- AbdAleati NS, Mohd Zaharim N, Mydin YO. Religiousness and mental health: Systematic review study. J Relig Health. 2016; 55(6):1929-37. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-014-9896-1] [PMID]

- Riley BB, Perna R, Tate DG, Forchheimer M, Anderson C, Luera G. Types of spiritual well-being among persons with chronic illness: Their relation to various forms of quality of life. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998; 79(3):258-64. [DOI:10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90004-1] [PMID]

- Cheraghi M, Molavi H. [The relation between the various dimensions of religiosity and public health in Isfahan university students (Persian)]. J Educ Psychol Stud. 2006; 2(2):1-22. [Link]

- Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry. 2012; 2012:278730. [DOI:10.5402/2012/278730] [PMID]

- Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Perez LM. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. J Clin Psychol. 2000; 56(4):519-43. [DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(200004)56:43.0.CO;2-1]

- Yousefi H, Abedi HA. Spiritual care in hospitalized patients. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2011; 16(1):125. [PMID]

- Hodge DR. Spiritually modified cognitive therapy: A review of the literature. Soc Work. 2006; 51(2):157-66. [DOI:10.1093/sw/51.2.157] [PMID]

- Moritz S, Kelly MT, Xu TJ, Toews J, Rickhi B. A spirituality teaching program for depression: Qualitative findings on cognitive and emotional change. Complement Ther Med. 2011; 19(4):201-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.ctim.2011.05.006] [PMID]

- Gholami A, Bashildeh K. [Effectiveness of spiritual therapy on women’s mental health (Persian)]. J Fam Consult Psychother. 2013; 1(3):331-48. [Link]

- Fallahikhoshknab M, Ghazanfari N. [Effectiveness of spiritual-vaccational therapy on self care of schizophrenics (Persian)]. Journal of Nursing Research. 2007; 2(4,5):25-30. [Link]

- Longshore D, Anglin MD, Conner BT. Are religiosity and spirituality useful constructs in drug treatment research? J Behav Health Serv Res. 2009; 36(2):177-88. [DOI:10.1007/s11414-008-9152-0] [PMID]

- Ralph S, Taylor CM. Nursing diagnosis reference Manual. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Link]

- Hosseini M, Salehi A, Fallahi Khoshknab M, Rokofian A, Davidson PM. The effect of a preoperative spiritual/religious intervention on anxiety in Shia Muslim patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A randomized controlled trial. J Holist Nurs. 2013; 31(3):164-72. [DOI:10.1177/0898010113488242] [PMID]

- McCullough ME, Larson DB. Religion and depression: A review of the literature. Twin Res. 1999; 2(2):126-36. [DOI:10.1375/136905299320565997]

- Chan MF, Chung LY, Lee AS, Wong WK, Lee GS, Lau CY, et al. Investigating spiritual care perceptions and practice patterns in Hong Kong nurses: Results of a cluster analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2006; 26(2):139-50. [DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2005.08.006] [PMID]

- Salajegheh S, Raghibi M. [The effect of combined therapy of spiritual-cognitive group therapy on death anxiety in patients with cancer (Persian)]. J Shahid Sadoughi Univ Med Sci. 2014; 22(2):1130-9. [Link]

- Gonçalves JP, Lucchetti G, Menezes PR, Vallada H. Religious and spiritual interventions in mental health care: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Psychol Med. 2015; 45(14):2937-49. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291715001166] [PMID]

- Heidari Gorji MA, Ghorbani Vajargah P, Salami Kohan K, Mollaei A, Falakdami A, Goudarzian AH, et al. The relationship between spirituality and religiosity with death anxiety among cancer patients: A systematic review. J Relig Health. 2024; 63(5):3597-617. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-024-02016-5] [PMID]

- Anderson N, Heywood-Everett S, Siddiqi N, Wright J, Meredith J, McMillan D. Faith-adapted psychological therapies for depression and anxiety: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2015; 176:183-96. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.019] [PMID]

- Khodayarifard M, Yonesi J, Akbari Zardkhaneh S, Fagihi A, Behpajouh A. [Group and individual cognitive behavioral therapy based on prisoners’ religious knowledge (Persian)]. J Search Psychol Health. 2009; 3(4):55-67. [Link]

- Captari LE, Hook JN, Hoyt W, Davis DE, McElroy-Heltzel SE, Worthington EL Jr. Integrating clients' religion and spirituality within psychotherapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol. 2018; 74(11):1938-51. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.22681] [PMID]

- Tutzer F, Schurr T, Frajo-Apor B, Pardeller S, Plattner B, Schmit A, et al. Relevance of spirituality and perceived social support to mental health of people with pre-existing mental health disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal investigation. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2024; 59(8):1437-48. [DOI:10.1007/s00127-023-02590-1] [PMID]

- Faraji J, Fallahikhoshknab M, Khankeh HR. Effectiveness of Poetry therapy on depression in elderly residents of a nursing home in Arak-Iran. Iran J Psychiatr Nurs. 2013; 1(1):55-62. [Link]

- Oh PJ, Kim YH. [Meta-analysis of spiritual intervention studies on biological, psychological, and spiritual outcomes (Korean)]. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2012; 42(6):833-42. [DOI:10.4040/jkan.2012.42.6.833] [PMID]

- De Diego-Cordero R, Iglesias-Romo M, Badanta B, Lucchetti G, Vega-Escaño J. Burnout and spirituality among nurses: A scoping review. Explore (NY). 2022; 18(5):612-20. [DOI:10.1016/j.explore.2021.08.001] [PMID]

- Worthington EL Jr, Hook JN, Davis DE, McDaniel MA. Religion and spirituality in psychotherapy: A meta-analytic review. Psychother Res. 2011; 21(1):1-15. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.20760]

- Rosmarin DH, Pargament KI, Pirutinsky S, Mahoney A. A randomized controlled evaluation of a spiritually integrated treatment for subclinical anxiety in the Jewish community, delivered via the Internet. J Anxiety Disord. 2010; 24(7):799-808. [DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.05.014] [PMID]

- van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, Bouter L; Editorial Board of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Updated method guidelines for systematic reviews in the cochrane collaboration back review group. Spine. 2003; 28(12):1290-9. [DOI:10.1097/01.BRS.0000065484.95996.AF] [PMID]

- Mir Bagher AjorPaz N, Ranjbar N. [Effects of recitation of holy quran on anxiety of women before cesarean section: A randomize clinical trial (Persian)]. Qom Univ Med Sci J. 2010; 4 (1):15-9. [Link]

- Bayanzadeh S, Bolhary J, Dadfar M, Karimi Keisomi I. [Effectiveness of Cognitive-Behavioral Religious - Cultural Therapy in Improvement of Obsessive-Compulsive Patients (Persian)]. Razi J Med Sci. 2005; 11 (44):913-23. [Link]

- Akoochekian S, Jamshidian Z, Marathi M, Almasi A, Davrpanah Jezi AH. [The effect of religious psychotherapy on obsessive symptoms and concomitant symptoms in obsessive patients with religious content (Persian)]. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2010; 28(114):11-801. [Link]

- Shojaei S, Abbasi M, Rahimi T, Vahedian M, Farhadloo R, Movahed E, et al. [The effect of religious care by the clergyman next to the patients’ bedside on their depression and anxiety (Persian)]. J Res Relig Health. 2018; 4(3):45-55. [DOI:10.22037/jrrh.v4i3.15911]

- Amini M, Samadi H, Yousefi R, Mehdizadeh M, Khorashadizadeh F, Shakri M. [Investigating the effectiveness of teaching life skills based on Quranic verses on students’ religious orientation and general health (Persian)]. J North Khorasan Univ Med Sci. 2021; 13(2):31-7. [DOI:10.52547/nkums.13.2.31]

- Musi Zadeh H, Merqati Khoei E, Asgharanjad Farid AA, Merqati Khoei T, Sedkiani Far A, Mutolian SA. [Investigating the effect of dialectical-behavioral therapy with a religious approach to treat violence against sexual partners in men, Urmia, 1387-1386 (clinical trial) (Persian)]. Urmia Univ Med Sci. 2014; 10(3):1-11. [Link]

- Yaghubi H, Sohrabi F, Mohammadzadeh A. [The comparison of cognitive behavior therapy and Islamic based spiritual religion psychotherapy on reducing of students overt anxiety (Persian)]. J Res Behav Sci. 2012; 10(2):1. [Link]

- Ebrahimi A, Neshatdoost HT, Mousavi SG, Asadollahi GA, Nasiri H. Controlled randomized clinical trial of spirituality integrated psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy and medication intervention on depressive symptoms and dysfunctional attitudes in patients with dysthymic disorder. Adv Biomed Res. 2013; 2:53. [DOI:10.4103/2277-9175.114201] [PMID]

- Ebrahimi H, Kazemi AH, Fallahi Khoshknab M, Modabber R. The effect of spiritual and religious group psychotherapy on suicidal ideation in depressed patients: A randomized clinical trial. J Caring Sci. 2014; 3(2):131-40. [PMID]

- Mahdavi B, Fallahi-Khoshknab M, Mohammadi F, Hosseini MA, Haghi M. Effects of spiritual group therapy on caregiver strain in home caregivers of the elderly with alzheimer's disease. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2017; 31(3):269-73. [DOI:10.1016/j.apnu.2016.12.003] [PMID]

- Shafiee Z, Zandiyeh Z, Moeini M, Gholami A. The effect of spiritual intervention on postmenopausal depression in women referred to urban healthcare centers in Isfahan: A double-blind clinical trial. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2016; 5(1):e32990. [DOI:10.17795/nmsjournal32990] [PMID]

- Nikfarjam M, Solati K, Heidari-Soureshjani S, Safavi P, Zarean E, Fallah E, et al. Effect of group religious intervention on spiritual health and reduction of symptoms in patients with anxiety. J Clin Diagn Res. 2018; 12(10):VC069. [DOI:10.7860/JCDR/2018/36291.12097]

- Edraki M, Noeezad Z, Bahrami R, Pourahmad S, Hadian Shirazi Z. Effect of spiritual care based on “ghalbe salim” model on anxiety among mothers with premature newborns admitted to neonatal intensive care units. Iran J Neonatol. 2019; 10(1):50-7. [Link]

- Yaghubi M, Abdekhoda M, Khani S. Effectiveness of religious-spiritual group therapy on spiritual health and quality of life in methadone-treated patients: A randomized clinical trial. Addict Health. 2019; 11(3):156-64. [DOI:10.22122/ahj.v11i3.238] [PMID]

- Jabbari B, Mirghafourvand M, Sehhatie F, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S. The effect of holly quran voice with and without translation on stress, anxiety and depression during pregnancy: A randomized controlled trial. J Relig Health. 2020; 59(1):544-54. [DOI:10.1007/s10943-017-0417-x] [PMID]

- Haghighat M, Mirghafourvand M, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Malakouti J, Erfani M. The effect of spiritual counseling on stress and anxiety in pregnancy: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2018; 20(4):e64094. [DOI:10.5812/ircmj.64094]

- Allameh T, JabalAmeli M, Lorestani K, Akbari M. [The efficacy of Quran sound on anxiety and pain of patients under cesarean section with regional anesthesia: A randomized case-controlled clinical trial (Persian)]. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2013; 31(235):601-10. [Link]

- Ahmadifarazi M, Khanzadeh M, Abdolali S, Moosavizadeh SR, Moosavizadeh S. [Efficacy of addiction cognitive-spiritual group therapy on craving, emotional regulation and mental health of patients under methadone maintenance treatment (Persian)]. J Islam Life Style. 2022; 6(2):26-32. [Link]

Article Type: Systematic Review |

Subject:

Public Health

Received: 2024/12/21 | Accepted: 2025/02/10 | Published: 2025/04/21

Received: 2024/12/21 | Accepted: 2025/02/10 | Published: 2025/04/21

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |