Volume 10, Issue 4 (10-2025)

CJHR 2025, 10(4): 227-236 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: NA

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sarkar J, Sarkar C. Medical Education Infrastructure and Physician Volunteerism in Public Health Facilities. CJHR 2025; 10 (4) :227-236

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-425-en.html

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-425-en.html

1- Department of Life Sciences, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India

2- Department of Life Sciences, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India ,chiradeep.sarkar@gnkhalsa.edu.in

2- Department of Life Sciences, University of Mumbai, Mumbai, India ,

Full-Text [PDF 628 kb]

(86 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (519 Views)

Full-Text: (51 Views)

Introduction

Several factors, such as war, migration, lack of coherent government policies, low budgetary allocation, and the socioeconomic structure of the population, strain the existing health infrastructure of any country.

Medical volunteering is an important part of healthcare. Developing a database of medical professionals willing to volunteer their services during a crisis will help the government in community engagement, risk communication, and public-private sector partnerships. Even in peaceful times, medical volunteers can provide critical healthcare services to marginalized or underserved people and difficult-to-reach communities [1].

According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), by 2050, climate change could cause an additional 14.5 million deaths and 12.5 USD trillion in economic losses globally. Climate change will also burden an extra 1.1 USD trillion on already strained medical infrastructure and human resources [2]. Climate change’s secondary effects, such as hurricanes, floods, heatwaves, wildfires, increasing sea levels, and droughts, can create conditions for disease outbreaks [3]. This may create a pandemic or epidemic-like situation, which will demand medical practitioners, mainly volunteers.

From the COVID-19 pandemic, experts have realized that the first hundred days of the outbreak are crucial for managing the disease [4]. There will be a burden on the health infrastructure when there is a surge in demand. This is especially true in countries where healthcare systems may be less equipped, underfunded, and/or understaffed.

According to the 2023 report of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), volunteers of Doctors Without Borders/MSF provide medical care in more than 70 countries each year to people affected by war, starvation, diseases, disasters, and exclusion from healthcare. It also states that they conducted 16,459,000 outpatient consultations, administered 3,295,700 measles vaccines, and admitted 1,368,700 patients to MSF clinics worldwide [5]. The scope and reach of such programs underscore the growing need for volunteer engagement during crises.

In peaceful times, health professionals’ volunteering can improve community health outcomes [6]. Earlier studies have been conducted to understand physicians’ preferences for a ‘public-private mix’ of healthcare [7]. Few studies are available to understand individual, interpersonal, community, and societal determinants of health professionals’ behaviors in volunteering [8, 9]. Studies are also carried out to understand the barriers to volunteering among medical professionals. It shows personal and professional barriers like time constraints, transportation, medical supply issues, and concerns about ethical implications [10].

While these studies have shed light on individual motivations and challenges, there has been limited focus on how a country’s medical education infrastructure might shape the culture, readiness, and capacity for volunteerism among healthcare professionals (HCP). Medical colleges contribute to a stronger and efficient healthcare system by training HCP. A higher number of medical colleges and student intake can positively impact health indicators [11]. Consequently, there is a need to understand how the country’s medical education affects the physicians’ approach towards volunteering.

This study was designed to understand how the medical education infrastructure of the country influences the volunteering behaviors of private physicians in public healthcare facilities. By identifying whether and how educational capacity influences volunteer participation, the findings could inform targeted policy interventions—such as curriculum reforms, incentive structures, and strategic resource allocation—to enhance readiness for both routine service delivery and emergency response.

Materials and Methods

Using publicly available datasets from the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), Government of India. India, the world’s most populous country with approximately 1.46 billion people, accounts for 18% of the global population but occupies only 2.41% of the Earth’s land area. The country spans 3,287,263 square kilometers and is characterized by remarkable geographic and socio-cultural diversity. Approximately 80% of its population resides in rural areas, where access to quality, affordable healthcare remains a persistent challenge. This rural–urban divide makes India an important case study for understanding the dynamics of healthcare volunteering in relation to medical education infrastructure.

To bring down maternal and neonatal mortality rates, the government of India started a program called Pradhan mantri surakshit matrutava abhiyan (PMSMA), which was launched on 9th June 2016 by the MoHFW. Private-sector OBGY specialists, radiologists, or physicians were encouraged to provide voluntary services once a month at public health facilities where government-sector practitioners are not available or inadequate. They are expected to provide free antenatal (ANT) checkups on the 9th day of every month.

Study procedure

The data related to the total number of volunteers registered and who provided services was obtained from the MoHFW, Government of India [12]. This data is anonymous and publicly available on the MoHFW website. It is available until 17 December 2021.

Number of :union: territory (UT) wise medical schools and bachelor of medicine and bachelor of surgery (MBBS) seats were collected from the Central Bureau of Health Intelligence (CBHI), MoHFW [13].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis, mean, median, mode, and range, were calculated for the collected data. Spearman rank correlation coefficient, and Simple linear regression, were done to understand the relation between the number of volunteers provided services at public healthcare facilities, and number of medical schools per state and number of MBBS seats per state. Due to the presence of outliers and substantial variability across states, robust regression using the Huber M-estimator was applied to minimize the influence of extreme values, verify the stability of the observed associations and understand the nature of the relationship between the study variables, whereas the Spearman rank correlation coefficient is used to measure the strength of an association and the direction of the relationship between these variables. Online statistical software GraphPad was used for all the aforementioned statistical analyses.

Results

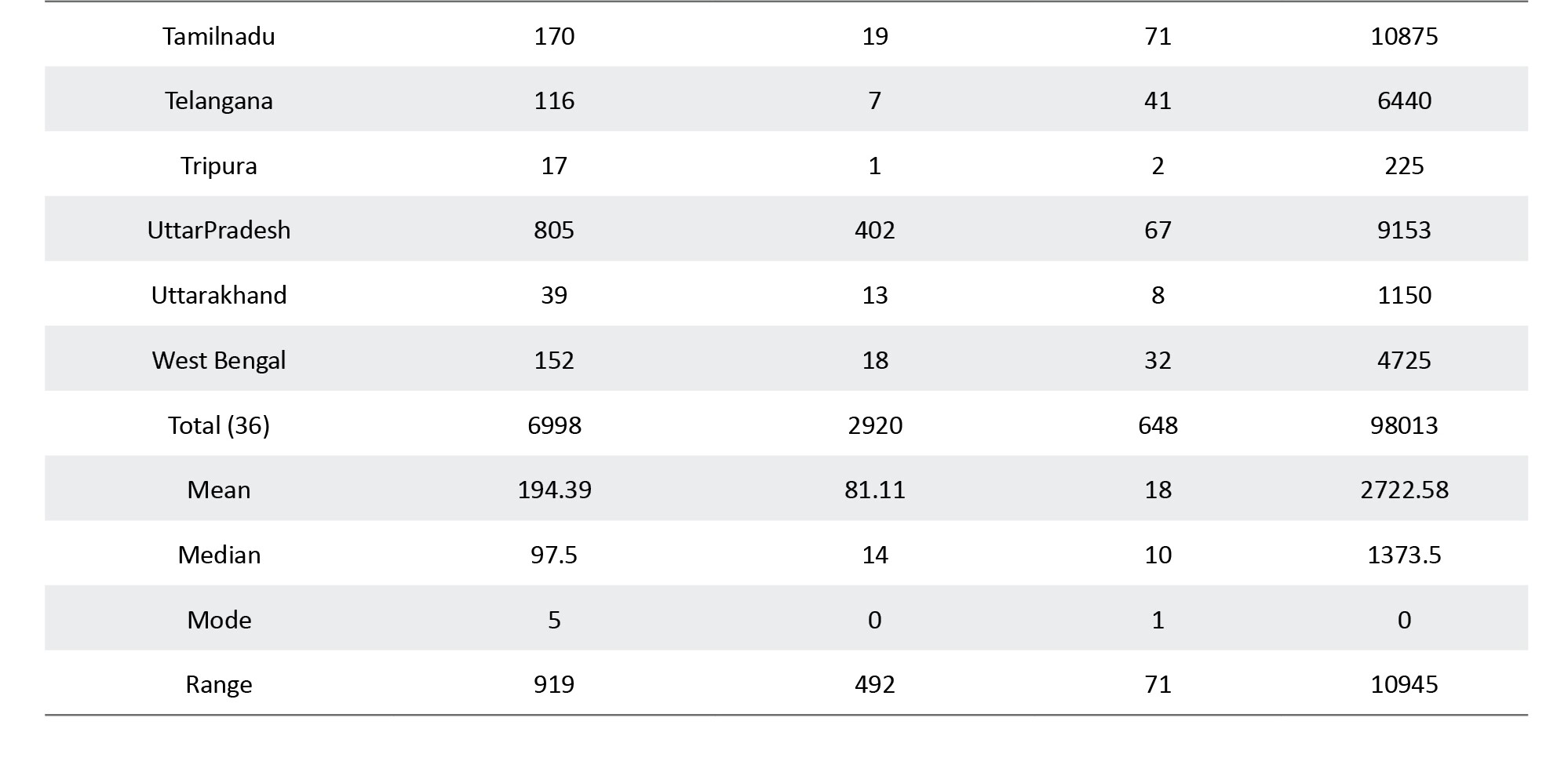

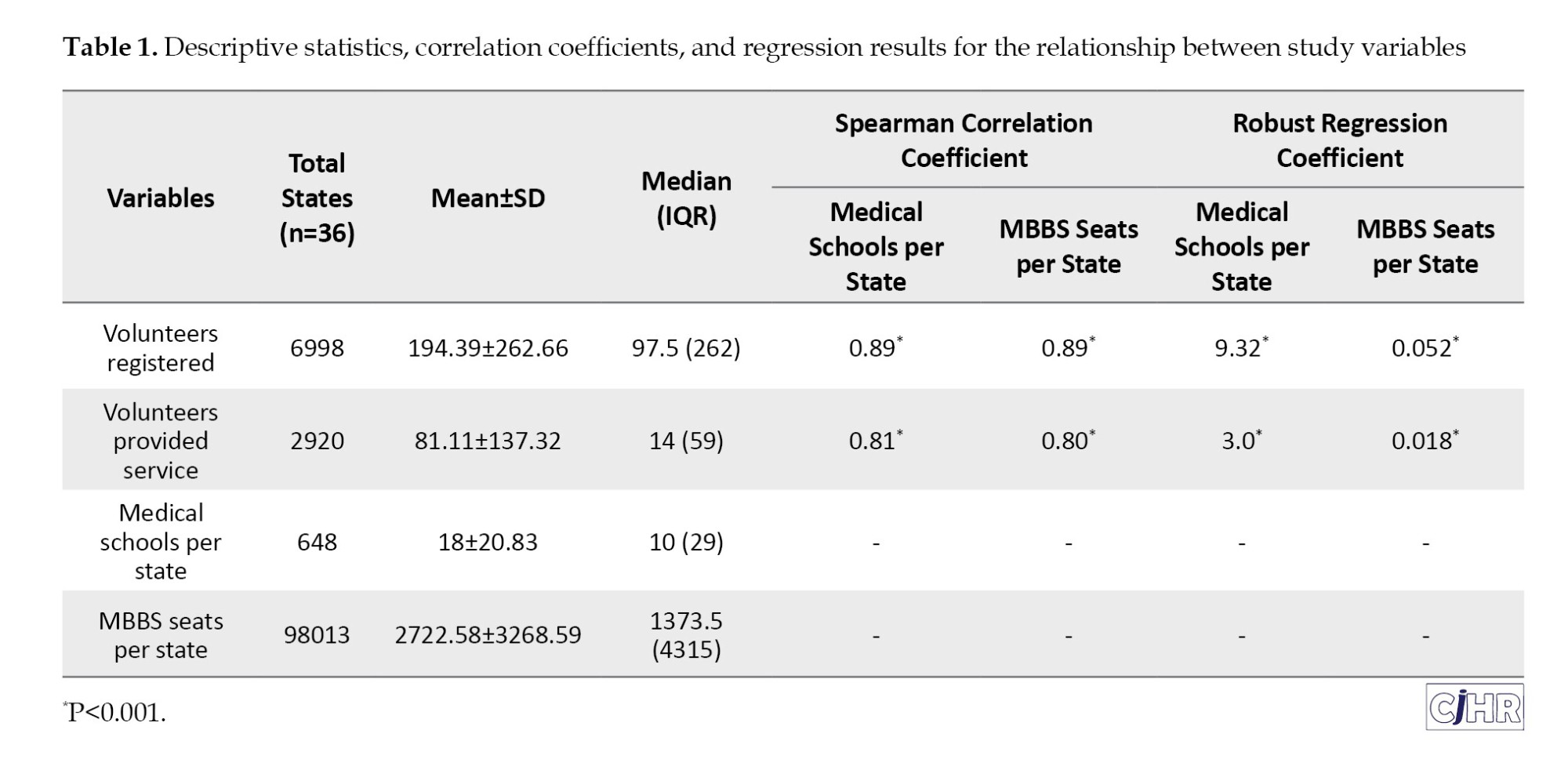

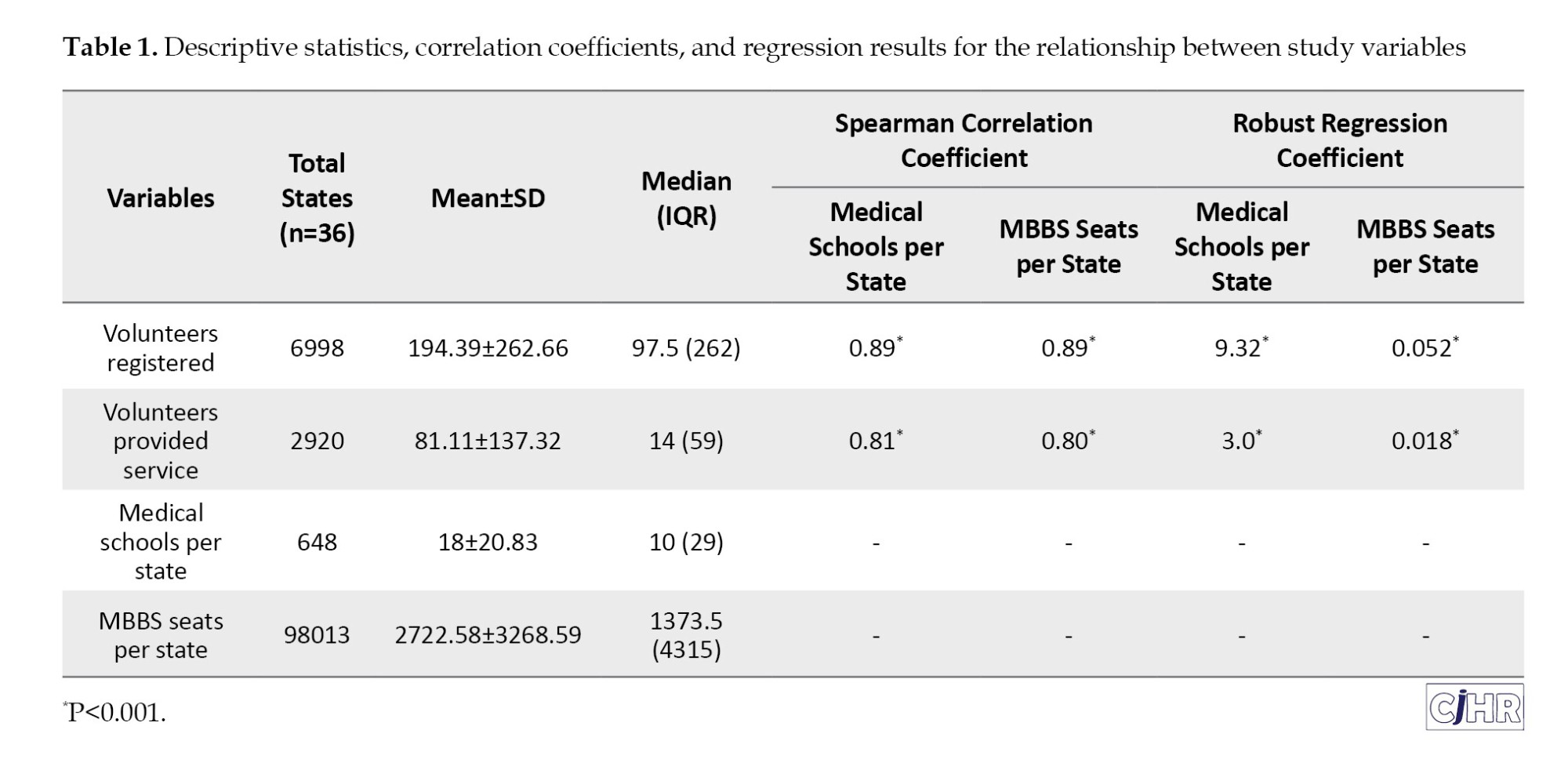

Across India, the number of private physicians who registered for the PMSMA volunteering program exceeded the number who actually provided services at public healthcare facilities (Table 1).

Out of 6,998 registered volunteers nationwide, only 2,920 (41.73%) actively participated (Figure 1). This participation gap of nearly 58% suggests the presence of systemic or individual barriers that limit the translation of willingness into action.

A detailed, state/UT-wise breakdown of these figures—including the number of medical schools, MBBS seats, and calculated participation rates—is provided in table of Appendix 1. This table shows that participation rates varied widely—from 0% in several regions (e.g. Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Arunachal Pradesh, Goa, Lakshadweep, Nagaland, Puducherry) to over 70% in states like Haryana and Dadra & Nagar Haveli. Such disparities point to potential influences from geographic accessibility, local healthcare needs, and policy implementation efficiency

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient showed a large and statistically significant positive correlation between the number of medical schools per state and the number of active volunteers (rₛ=0.8057, P<0.001), as well as between MBBS seats per state and active volunteers (rₛ=0.8024, P<0.001). These results indicate that states with more developed medical education infrastructure tend to have higher active volunteer participation, although correlation alone does not imply causation.

Simple linear regression indicated that for every additional medical school in a state, the number of active volunteers increased by an average of 3.5727 (P<0.001). In contrast, for every additional MBBS seat, the number of active volunteers increased by only 0.0228 (P<0.001). This suggests that the institutional presence of a medical school may be more influential on volunteer engagement than merely expanding seat capacity, potentially due to the role of faculty mentorship, institutional outreach, and the creation of a local medical community.

Discussion

The changing climate and geopolitics increase the threats of future global disease outbreaks and human conflicts, respectively. This will burden the existing health infrastructure and demand a more robust medical workforce in emergencies. This study examined the relationship between a country’s medical education infrastructure and the volunteering behavior of private physicians in underserved public healthcare facilities. We found a strong, statistically significant positive correlation between the number of medical schools and MBBS seats in a state and the number of physicians who actively volunteered.

Our study supports the idea that no country can quickly produce physicians in weeks or months during a crisis like war or a pandemic. Our study data on volunteers, for 2016 to 2021, shows that India, a country with a population of 1.46 billion, has only 6998 private physicians willing to serve as volunteers, but only 2920 have provided their service. Since October 7, 2023, in a few months in Gaza, more than 45,000 Palestinians and 1700 Israeli and foreign nationals have died [14]. In Ukraine, at least 12,456 civilians were killed from February 2022 to December 2024, including 669 children. Additionally, 28,382 adults and 1,833 children were injured [15]. Events like the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ukraine-Russia conflict, and the Gaza war highlight the need for countries to strengthen their medical infrastructure amid a changing climate and global political unrest.

Our results show that less than half the number of physicians who registered for volunteering have provided their services. This is similar to the study carried out among physicians in the USA. In the USA, volunteerism has received increasing attention in the national agenda for social change. But there was little information available about the community volunteer activity of the US physicians. The study carried out to measure the levels of community volunteerism among US physicians showed, despite highly favourable physician attitudes toward volunteerism, that less than half of US physicians have volunteered with community organizations. The study of USA physicians suggests that the working hours of physicians are a determining variable behind their volunteerism attitude [16].

Our study results show variation among the states in the number of medical schools and the number of MBBS seats. Few states have single or no medical schools; consequently, there are no volunteer physicians to provide services. We have noticed that the location of medical schools is an important variable, where our study shows Island :union: territories like Lakshwadeep or remote states of north-east India have no or one medical school. These findings of our study are also supported by earlier studies where the discrepancy is observed at the state as well as the urban and rural levels. Medical school density of provinces revealed a wide range from 0 (Nagaland, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Daman and Diu, and Lakshadweep) to 72.12 (Puducherry). These earlier findings significantly support the mal-distribution of medical schools in India, which is highlighted in our work [17].

A study carried out by Rizwan et. al., shows that the shortage of physicians and the uneven distribution of medical schools are not only a local or national phenomenon but a global phenomenon. One-third of all medical schools in the world are located in five countries, and nearly half are located in ten countries. There are approximately thirteen countries that do not have any medical schools. It reports global shortage of physicians is worse in developing countries. To overcome this, there has been a rapid expansion in the number of medical schools, nearly doubling in the past two decades. Recently, the countries with the most rapid growth of medical schools are Caribbean countries (40%), India (25%), and China (10%) [18]. Here too, we have noticed the Indian government’s policy to overcome the physicians shortage by attracting them as volunteers and increasing the number of medical schools to produce more doctors. Seeing this growth trend of rapid expansion of medical schools, it is important to focus on the quality and competency of these physicians

Our data shows a slight increase in medical volunteers when the number of medical colleges and MBBS seats increased. An increase in these parameters increases the total number of physicians. When China has increased the number of medical graduates by increasing the number of medical schools and class sizes, the numeric expansion of student enrollment in China leads to a decline in the quality of health professional education, due to a dearth of faculty numbers and other teaching resources [19]. Decline in the quality of education might be a probable reason that, though there is an increase in the total number of physicians, there is a small number of volunteers for service.

The current study shows that some areas have no medical colleges or only one, resulting in no volunteers. However, even in states with many medical colleges, the number of volunteers remains limited. The narrative review conducted by Hashem et al. explores the impacts of establishing new medical schools, highlighting their positive contributions to health, social, economic, and research outcomes in a region, with significant implications for the health workforce [20]. It also states that simply having a new medical school will have a limited impact on health equity, but medical schools that actively engage with communities to generate ideas, adapt processes, and build relationships can help reduce barriers to healthcare.

The objective of the government behind attracting private physicians to public healthcare facilities is to tackle the shortage of staff in public healthcare centers. Our results show that the program where physicians’ one visit per month is requested has not received a good response. Only 2920 private physicians provided their services. If privatization of medical education [21] or medical practice [22] is heavily incentivized, then getting active support for primary care, particularly for the poor, becomes difficult. Some studies recommend financial incentives like tax cuts and professional development opportunities to attract MBBS graduates to serve in rural or unprevileged areas [23]. Similar socio-economic motivational factors should be researched to create an attractive policy for private physicians to volunteer in underserved public healthcare facilities.

Our study shows several volunteers registered in every state is higher than the ones who provided service. This shows private physicians have a positive perception towards volunteering, but they cannot provide their services at public facilities for some reasons. This behavior is also shown in a study carried out to increase the number of physicians volunteering in safety net clinics for the uninsured and underinsured population of southern California. [24]. The most common barriers reported in this study are a lack of time and supply issues at the clinic, along with the patients’ social, transportation, and financial challenges.

Similar studies, like safety net clinics of Southern California, for Indian underserved public health facilities, should be carried out to understand the motivation and barriers for volunteering of private physicians. A study reports that, in India, almost 75% of physicians have faced some kind of violence during their professional practice [25]. This might be the major reason behind private physicians not joining a volunteering program. The poor economic status of the patients, the ever-rising cost of the treatment, and meager government spending on healthcare are the reasons behind such violent situations. Long waiting hours, poor communication, and negative media coverage are also related factors for violence against HCP.

More than 80% of Indian physicians’ have also reported stress, violence, harassment by police and politicians, studying for 10-15 years, lack of personal life, draconian laws and acts against physicians, and poor infrastructure in government institutions as reasons [26].

Health personnel are needed to achieve sustainable development goal 3 (SDG 3) of the United Nations of good health and well-being by 2030 [27]. Consequently, there is a need to identify areas in healthcare that can be assigned to health workers other than physicians by guiding or trained by physicians. Seeing the current challenges in the healthcare system, efficient use of available manpower, resources, and technology may come to help.Our earlier studies have shown that community health workers are crucial in improving maternal and child health within the community [28, 29]. However, leveraging innovative strategies by implementing technology can enhance outcomes, not only in improving child and maternal health but also overall public health [30, 31]. The combination(s) of community health workers, medical volunteers, and technology interventions should be applied to address the health crisis.

There is a growing need to strengthen health infrastructure for future disease outbreaks, crises like war, and climate change-related disasters. Strategic use of medical students, private and public physicians, community health workers, and technology can help achieve health equality.

Policy implications

The COVID-19 pandemic is not the last. In a healthcare crisis, the optimum use of physicians and other medical staff becomes an immediately available option, especially in the hinterlands of vast counties. Setting up a district-level team of healthcare workers with supervising physicians at the top can help countries struggling with a shortage of HCP or physicians. Such countries need to restructure primary healthcare in this way.

Even if some private medical practitioners want to volunteer, they cannot do so. There is a need for detailed studies to understand the reasons behind this behavior. Setting up new medical schools, or increasing the number of medical schools and increasing the number of MBBS seats will increase the number of physicians in the country, improving the number of physicians volunteering. While improving the quantity of medical education infrastructure, the quality of education should not be affected.

Unless and until the problems of health professionals are solved, they will remain reluctant to volunteer in the programs designed for underserved people. To solve the existing problems of medical health professionals, a complete overhaul of the current healthcare system is required. Workplace violence with health professionals is a major public health issue not only in India but throughout the world. Curriculum for healthcare students should be designed and periodic workshops for health professionals should be conducted to cover the soft skills to handle anxious patients.

Awareness campaigns are needed to reach the maximum number of private physicians. A data repository needs to be maintained to show the exact number of pregnant women or patients handled by individual voluntary physicians. This will help to design better strategies to implement the voulenteering program.

There is a need for improvement of government or public healthcare facilities in rural areas and urban slums as in these areas’ patients are poor and illiterate with lesser knowledge of hygiene practices and preventive measures for other diseases which makes these areas prone to future pandemics or epidemics.

There is a need for global research collaboration to achieve United Nations SDG 3 as well as to avoid vulnerability in future pandemics.

Conclusion

This study found a strong positive association between the scale of medical education infrastructure and the participation of private physicians in public healthcare volunteering in India, but also revealed a substantial gap between willingness and active service. Expanding the number of medical schools appears more influential than simply increasing MBBS seats, likely due to the institutional culture and networks they foster.

Limitations

This study has made significant contributions to the literature. A large population with geographical and ethnocultural diversity is a strength of this research. However, there are some limitations that should be addressed in future studies. The study relies on data from the MoHFW, Government of India. The limitations inherent to secondary data also apply to this dataset. The PMSMA data shows the total number of beneficiary pregnant women at empaneled medical facilities, but data on the exact number of pregnant women who received benefits through voluntary visits of medical practitioners is not available.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the MoHFW, Government of India for the open data of Pradhan Mantri Surakshit Matritva Abhiyan which became the foundation of this research study in public health.

References

Several factors, such as war, migration, lack of coherent government policies, low budgetary allocation, and the socioeconomic structure of the population, strain the existing health infrastructure of any country.

Medical volunteering is an important part of healthcare. Developing a database of medical professionals willing to volunteer their services during a crisis will help the government in community engagement, risk communication, and public-private sector partnerships. Even in peaceful times, medical volunteers can provide critical healthcare services to marginalized or underserved people and difficult-to-reach communities [1].

According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), by 2050, climate change could cause an additional 14.5 million deaths and 12.5 USD trillion in economic losses globally. Climate change will also burden an extra 1.1 USD trillion on already strained medical infrastructure and human resources [2]. Climate change’s secondary effects, such as hurricanes, floods, heatwaves, wildfires, increasing sea levels, and droughts, can create conditions for disease outbreaks [3]. This may create a pandemic or epidemic-like situation, which will demand medical practitioners, mainly volunteers.

From the COVID-19 pandemic, experts have realized that the first hundred days of the outbreak are crucial for managing the disease [4]. There will be a burden on the health infrastructure when there is a surge in demand. This is especially true in countries where healthcare systems may be less equipped, underfunded, and/or understaffed.

According to the 2023 report of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), volunteers of Doctors Without Borders/MSF provide medical care in more than 70 countries each year to people affected by war, starvation, diseases, disasters, and exclusion from healthcare. It also states that they conducted 16,459,000 outpatient consultations, administered 3,295,700 measles vaccines, and admitted 1,368,700 patients to MSF clinics worldwide [5]. The scope and reach of such programs underscore the growing need for volunteer engagement during crises.

In peaceful times, health professionals’ volunteering can improve community health outcomes [6]. Earlier studies have been conducted to understand physicians’ preferences for a ‘public-private mix’ of healthcare [7]. Few studies are available to understand individual, interpersonal, community, and societal determinants of health professionals’ behaviors in volunteering [8, 9]. Studies are also carried out to understand the barriers to volunteering among medical professionals. It shows personal and professional barriers like time constraints, transportation, medical supply issues, and concerns about ethical implications [10].

While these studies have shed light on individual motivations and challenges, there has been limited focus on how a country’s medical education infrastructure might shape the culture, readiness, and capacity for volunteerism among healthcare professionals (HCP). Medical colleges contribute to a stronger and efficient healthcare system by training HCP. A higher number of medical colleges and student intake can positively impact health indicators [11]. Consequently, there is a need to understand how the country’s medical education affects the physicians’ approach towards volunteering.

This study was designed to understand how the medical education infrastructure of the country influences the volunteering behaviors of private physicians in public healthcare facilities. By identifying whether and how educational capacity influences volunteer participation, the findings could inform targeted policy interventions—such as curriculum reforms, incentive structures, and strategic resource allocation—to enhance readiness for both routine service delivery and emergency response.

Materials and Methods

Using publicly available datasets from the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), Government of India. India, the world’s most populous country with approximately 1.46 billion people, accounts for 18% of the global population but occupies only 2.41% of the Earth’s land area. The country spans 3,287,263 square kilometers and is characterized by remarkable geographic and socio-cultural diversity. Approximately 80% of its population resides in rural areas, where access to quality, affordable healthcare remains a persistent challenge. This rural–urban divide makes India an important case study for understanding the dynamics of healthcare volunteering in relation to medical education infrastructure.

To bring down maternal and neonatal mortality rates, the government of India started a program called Pradhan mantri surakshit matrutava abhiyan (PMSMA), which was launched on 9th June 2016 by the MoHFW. Private-sector OBGY specialists, radiologists, or physicians were encouraged to provide voluntary services once a month at public health facilities where government-sector practitioners are not available or inadequate. They are expected to provide free antenatal (ANT) checkups on the 9th day of every month.

Study procedure

The data related to the total number of volunteers registered and who provided services was obtained from the MoHFW, Government of India [12]. This data is anonymous and publicly available on the MoHFW website. It is available until 17 December 2021.

Number of :union: territory (UT) wise medical schools and bachelor of medicine and bachelor of surgery (MBBS) seats were collected from the Central Bureau of Health Intelligence (CBHI), MoHFW [13].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis, mean, median, mode, and range, were calculated for the collected data. Spearman rank correlation coefficient, and Simple linear regression, were done to understand the relation between the number of volunteers provided services at public healthcare facilities, and number of medical schools per state and number of MBBS seats per state. Due to the presence of outliers and substantial variability across states, robust regression using the Huber M-estimator was applied to minimize the influence of extreme values, verify the stability of the observed associations and understand the nature of the relationship between the study variables, whereas the Spearman rank correlation coefficient is used to measure the strength of an association and the direction of the relationship between these variables. Online statistical software GraphPad was used for all the aforementioned statistical analyses.

Results

Across India, the number of private physicians who registered for the PMSMA volunteering program exceeded the number who actually provided services at public healthcare facilities (Table 1).

Out of 6,998 registered volunteers nationwide, only 2,920 (41.73%) actively participated (Figure 1). This participation gap of nearly 58% suggests the presence of systemic or individual barriers that limit the translation of willingness into action.

A detailed, state/UT-wise breakdown of these figures—including the number of medical schools, MBBS seats, and calculated participation rates—is provided in table of Appendix 1. This table shows that participation rates varied widely—from 0% in several regions (e.g. Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Arunachal Pradesh, Goa, Lakshadweep, Nagaland, Puducherry) to over 70% in states like Haryana and Dadra & Nagar Haveli. Such disparities point to potential influences from geographic accessibility, local healthcare needs, and policy implementation efficiency

Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient showed a large and statistically significant positive correlation between the number of medical schools per state and the number of active volunteers (rₛ=0.8057, P<0.001), as well as between MBBS seats per state and active volunteers (rₛ=0.8024, P<0.001). These results indicate that states with more developed medical education infrastructure tend to have higher active volunteer participation, although correlation alone does not imply causation.

Simple linear regression indicated that for every additional medical school in a state, the number of active volunteers increased by an average of 3.5727 (P<0.001). In contrast, for every additional MBBS seat, the number of active volunteers increased by only 0.0228 (P<0.001). This suggests that the institutional presence of a medical school may be more influential on volunteer engagement than merely expanding seat capacity, potentially due to the role of faculty mentorship, institutional outreach, and the creation of a local medical community.

Discussion

The changing climate and geopolitics increase the threats of future global disease outbreaks and human conflicts, respectively. This will burden the existing health infrastructure and demand a more robust medical workforce in emergencies. This study examined the relationship between a country’s medical education infrastructure and the volunteering behavior of private physicians in underserved public healthcare facilities. We found a strong, statistically significant positive correlation between the number of medical schools and MBBS seats in a state and the number of physicians who actively volunteered.

Our study supports the idea that no country can quickly produce physicians in weeks or months during a crisis like war or a pandemic. Our study data on volunteers, for 2016 to 2021, shows that India, a country with a population of 1.46 billion, has only 6998 private physicians willing to serve as volunteers, but only 2920 have provided their service. Since October 7, 2023, in a few months in Gaza, more than 45,000 Palestinians and 1700 Israeli and foreign nationals have died [14]. In Ukraine, at least 12,456 civilians were killed from February 2022 to December 2024, including 669 children. Additionally, 28,382 adults and 1,833 children were injured [15]. Events like the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ukraine-Russia conflict, and the Gaza war highlight the need for countries to strengthen their medical infrastructure amid a changing climate and global political unrest.

Our results show that less than half the number of physicians who registered for volunteering have provided their services. This is similar to the study carried out among physicians in the USA. In the USA, volunteerism has received increasing attention in the national agenda for social change. But there was little information available about the community volunteer activity of the US physicians. The study carried out to measure the levels of community volunteerism among US physicians showed, despite highly favourable physician attitudes toward volunteerism, that less than half of US physicians have volunteered with community organizations. The study of USA physicians suggests that the working hours of physicians are a determining variable behind their volunteerism attitude [16].

Our study results show variation among the states in the number of medical schools and the number of MBBS seats. Few states have single or no medical schools; consequently, there are no volunteer physicians to provide services. We have noticed that the location of medical schools is an important variable, where our study shows Island :union: territories like Lakshwadeep or remote states of north-east India have no or one medical school. These findings of our study are also supported by earlier studies where the discrepancy is observed at the state as well as the urban and rural levels. Medical school density of provinces revealed a wide range from 0 (Nagaland, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Daman and Diu, and Lakshadweep) to 72.12 (Puducherry). These earlier findings significantly support the mal-distribution of medical schools in India, which is highlighted in our work [17].

A study carried out by Rizwan et. al., shows that the shortage of physicians and the uneven distribution of medical schools are not only a local or national phenomenon but a global phenomenon. One-third of all medical schools in the world are located in five countries, and nearly half are located in ten countries. There are approximately thirteen countries that do not have any medical schools. It reports global shortage of physicians is worse in developing countries. To overcome this, there has been a rapid expansion in the number of medical schools, nearly doubling in the past two decades. Recently, the countries with the most rapid growth of medical schools are Caribbean countries (40%), India (25%), and China (10%) [18]. Here too, we have noticed the Indian government’s policy to overcome the physicians shortage by attracting them as volunteers and increasing the number of medical schools to produce more doctors. Seeing this growth trend of rapid expansion of medical schools, it is important to focus on the quality and competency of these physicians

Our data shows a slight increase in medical volunteers when the number of medical colleges and MBBS seats increased. An increase in these parameters increases the total number of physicians. When China has increased the number of medical graduates by increasing the number of medical schools and class sizes, the numeric expansion of student enrollment in China leads to a decline in the quality of health professional education, due to a dearth of faculty numbers and other teaching resources [19]. Decline in the quality of education might be a probable reason that, though there is an increase in the total number of physicians, there is a small number of volunteers for service.

The current study shows that some areas have no medical colleges or only one, resulting in no volunteers. However, even in states with many medical colleges, the number of volunteers remains limited. The narrative review conducted by Hashem et al. explores the impacts of establishing new medical schools, highlighting their positive contributions to health, social, economic, and research outcomes in a region, with significant implications for the health workforce [20]. It also states that simply having a new medical school will have a limited impact on health equity, but medical schools that actively engage with communities to generate ideas, adapt processes, and build relationships can help reduce barriers to healthcare.

The objective of the government behind attracting private physicians to public healthcare facilities is to tackle the shortage of staff in public healthcare centers. Our results show that the program where physicians’ one visit per month is requested has not received a good response. Only 2920 private physicians provided their services. If privatization of medical education [21] or medical practice [22] is heavily incentivized, then getting active support for primary care, particularly for the poor, becomes difficult. Some studies recommend financial incentives like tax cuts and professional development opportunities to attract MBBS graduates to serve in rural or unprevileged areas [23]. Similar socio-economic motivational factors should be researched to create an attractive policy for private physicians to volunteer in underserved public healthcare facilities.

Our study shows several volunteers registered in every state is higher than the ones who provided service. This shows private physicians have a positive perception towards volunteering, but they cannot provide their services at public facilities for some reasons. This behavior is also shown in a study carried out to increase the number of physicians volunteering in safety net clinics for the uninsured and underinsured population of southern California. [24]. The most common barriers reported in this study are a lack of time and supply issues at the clinic, along with the patients’ social, transportation, and financial challenges.

Similar studies, like safety net clinics of Southern California, for Indian underserved public health facilities, should be carried out to understand the motivation and barriers for volunteering of private physicians. A study reports that, in India, almost 75% of physicians have faced some kind of violence during their professional practice [25]. This might be the major reason behind private physicians not joining a volunteering program. The poor economic status of the patients, the ever-rising cost of the treatment, and meager government spending on healthcare are the reasons behind such violent situations. Long waiting hours, poor communication, and negative media coverage are also related factors for violence against HCP.

More than 80% of Indian physicians’ have also reported stress, violence, harassment by police and politicians, studying for 10-15 years, lack of personal life, draconian laws and acts against physicians, and poor infrastructure in government institutions as reasons [26].

Health personnel are needed to achieve sustainable development goal 3 (SDG 3) of the United Nations of good health and well-being by 2030 [27]. Consequently, there is a need to identify areas in healthcare that can be assigned to health workers other than physicians by guiding or trained by physicians. Seeing the current challenges in the healthcare system, efficient use of available manpower, resources, and technology may come to help.Our earlier studies have shown that community health workers are crucial in improving maternal and child health within the community [28, 29]. However, leveraging innovative strategies by implementing technology can enhance outcomes, not only in improving child and maternal health but also overall public health [30, 31]. The combination(s) of community health workers, medical volunteers, and technology interventions should be applied to address the health crisis.

There is a growing need to strengthen health infrastructure for future disease outbreaks, crises like war, and climate change-related disasters. Strategic use of medical students, private and public physicians, community health workers, and technology can help achieve health equality.

Policy implications

The COVID-19 pandemic is not the last. In a healthcare crisis, the optimum use of physicians and other medical staff becomes an immediately available option, especially in the hinterlands of vast counties. Setting up a district-level team of healthcare workers with supervising physicians at the top can help countries struggling with a shortage of HCP or physicians. Such countries need to restructure primary healthcare in this way.

Even if some private medical practitioners want to volunteer, they cannot do so. There is a need for detailed studies to understand the reasons behind this behavior. Setting up new medical schools, or increasing the number of medical schools and increasing the number of MBBS seats will increase the number of physicians in the country, improving the number of physicians volunteering. While improving the quantity of medical education infrastructure, the quality of education should not be affected.

Unless and until the problems of health professionals are solved, they will remain reluctant to volunteer in the programs designed for underserved people. To solve the existing problems of medical health professionals, a complete overhaul of the current healthcare system is required. Workplace violence with health professionals is a major public health issue not only in India but throughout the world. Curriculum for healthcare students should be designed and periodic workshops for health professionals should be conducted to cover the soft skills to handle anxious patients.

Awareness campaigns are needed to reach the maximum number of private physicians. A data repository needs to be maintained to show the exact number of pregnant women or patients handled by individual voluntary physicians. This will help to design better strategies to implement the voulenteering program.

There is a need for improvement of government or public healthcare facilities in rural areas and urban slums as in these areas’ patients are poor and illiterate with lesser knowledge of hygiene practices and preventive measures for other diseases which makes these areas prone to future pandemics or epidemics.

There is a need for global research collaboration to achieve United Nations SDG 3 as well as to avoid vulnerability in future pandemics.

Conclusion

This study found a strong positive association between the scale of medical education infrastructure and the participation of private physicians in public healthcare volunteering in India, but also revealed a substantial gap between willingness and active service. Expanding the number of medical schools appears more influential than simply increasing MBBS seats, likely due to the institutional culture and networks they foster.

Limitations

This study has made significant contributions to the literature. A large population with geographical and ethnocultural diversity is a strength of this research. However, there are some limitations that should be addressed in future studies. The study relies on data from the MoHFW, Government of India. The limitations inherent to secondary data also apply to this dataset. The PMSMA data shows the total number of beneficiary pregnant women at empaneled medical facilities, but data on the exact number of pregnant women who received benefits through voluntary visits of medical practitioners is not available.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the MoHFW, Government of India for the open data of Pradhan Mantri Surakshit Matritva Abhiyan which became the foundation of this research study in public health.

References

- Woldie M, Feyissa GT, Admasu B, Hassen K, Mitchell K, Mayhew S, et al. Community health volunteers could help improve access to and use of essential health services by communities in LMICs: An umbrella review. Health Policy Plann. 2018; 33(10):1128–43. [DOI:10.1093/heapol/czy094]

- World Economic Forum. Quantifying the impact of climate change on human health [Internet]. 2024 [Updated 2024 January 16]. Available from: [Link]

- Piscitelli P, Miani A. Climate Change and Infectious Diseases: Navigating the intersection through innovation and interdisciplinary approaches. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024; 21(3):314. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph21030314]

- Gouglas D, Christodoulou M, Hatchett R. The 100 days mission—2022 global pandemic preparedness summit. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023; 29(3):e221142. [DOI:10.3201/eid2903.221142] [PMCID]

- Médecins Sans Frontière. International activity report [Internet]. 2023 [Updated 2024 July 19]. Available from: [Link]

- Strkljevic I, Tiedemann A, Souza de Oliveira J, Haynes A, Sherrington C. Health professionals’ involvement in volunteering their professional skills: A scoping review. Front Med. 2024; 11:1368661. [DOI:10.3389/fmed.2024.1368661]

- Scott A, Holte JH, Witt J. Preferences of physicians for public and private sector work. Hum Resour Health. 2020; 18(1):59. [DOI:10.1186/s12960-020-00498-4]

- Kim EJ, Fox S, Moretti ME, Turner M, Girard TD, Chan SY. Motivations and barriers associated with physician volunteerism for an international telemedicine organization. Front Public Health. 2019; 7:224. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2019.00224]

- Kindermann D, Jenne MP, Schmid C, Bozorgmehr K, Wahedi K, Junne F, et al. Motives, experiences and psychological strain in medical students engaged in refugee care in a reception center–a mixed-methods approach. BMC Med Educ 2019; 19(1):302. [DOI:10.1186/s12909-019-1730-8]

- AlOmar RS, AlShamlan NA, AlAmer NA, Aldulijan F, AlMuhaidib S, Almukhadhib O, et al. What are the barriers and facilitators of volunteering among healthcare students during the COVID-19 pandemic? A Saudi-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2021; 11(2):e042910. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-042910]

- Mondal H, Soni S, Juyal A, Behera JK, Mondal S. Current distribution of medical colleges in India and its potential predictors: A public domain data audit. J Fam Med Prim Care. 2023; 12(6):1072-7. [DOI:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1558_22]

- MoHFW-Digital Sansad. Pradhan mantri surakshit matritva abhiyan (PMSMA). New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2021. [Link]

- Central Bureau of Health Intelligence (CBHI). National Health Profile [Internet]. 2022 [Updated 2025 October 22]. Available from: [Link]

- United Nations. Noting more than 45,000 Palestinians have been killed in gaza, assistant secretary-general tells security council ‘ceasefire is long overdue [Internet]. 2025 [Updated 2025 July 13]. Available from: [Link]

- United Nations. New year sees uptick and expansion of fighting on Ukraine’s frontlines [Internet]. 2025 [Updated 2025 January 16]. Available from: [Link]

- Grande D, Armstrong K. Community volunteerism of US physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23(12):1987-91. [DOI:10.1007/s11606-008-0811-x]

- Sabde Y, Diwan V, Mahadik VK, Parashar V, Negandhi H, Trushna T, et al. Medical schools in India: Pattern of establishment and impact on public health-a Geographic Information System (GIS) based exploratory study. BMC Public Health. 2020; 20(1):755. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-020-08797-0]

- Rizwan M, Rosson NJ, Tackett S, Hassoun HT. Globalization of medical education: Current trends and opportunities for medical students. J Med Educ Train. 2018; 2:035. [Link]

- Wang W. Medical education in China: Progress in the past 70 years and a vision for the future. BMC Med Educ. 2021; 21(1):453. [DOI:10.1186/s12909-021-02875-6]

- Hashem F, Marchand C, Peckham S, Peckham A. What are the impacts of setting up new medical schools? A narrative review. BMC Med Educ. 2022; 22(1):759. [DOI:10.1186/s12909-022-03835-4]

- Scheffer MC, Dal Poz MR. The privatization of medical education in Brazil: Trends and challenges. Human Resour Health. 2015; 13(1):96. [DOI:10.1186/s12960-015-0095-2]

- Keshri VR, Sriram V, Baru R. Reforming the regulation of medical education, professionals and practice in India. BMJ Glob Health. 2020; 5(8):e002765. [DOI:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002765]

- Brahmapurkar K, Zodpey S, Sabde Y, Brahmapurkar V. The need to focus on medical education in rural districts of India. Natl Med J India. 2018; 31(3):164. [DOI:10.4103/0970-258X.255761] [PMID]

- Mcgeehan L, Takehara MA, Daroszewski E. Physicians' Perceptions of volunteer service at safety-net clinics. Perm J. 2017; 21:16-003. [DOI:10.7812/TPP/16-003] [PMID]

- Dora SS, Batool H, Nishu RI, Hamid P. Workplace violence against doctors in India: A traditional review. Cureus. 2020; 12(6):e8706. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.8706]

- Gadapati S, Shamanna BR. A review on violence against health care professionals in India and its impact. Natl J Commun Med. 2023; 14(8):525-33. [DOI:10.55489/njcm.140820233112]

- United Nations. Resolution adopted by the general assembly on 25th September 2015. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development [Internet]. 2015 [Updated 2025 October 1]. Available from: [Link]

- Sarkar J, Sarkar C. Designing strategies to reach the maximum number of women for comprehensive knowledge of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Adv Med Pharm Dent Res. 2024; 4(2):207–7. [DOI:10.21622/AMPDR.2024.04.2.941]

- Sarkar J, Sarkar C. Role of community infrastructure in improving nutrition in under-five children. J Client Centred Nurs Care. 2025; 11(1):23-34. [Link]

- Sarkar J, Sarkar C. Comparative analysis of individual-level and community-level approaches for achieving sustainable development goals for the under-five mortality rate. Avicenna. 2025; 2025(1):2. [DOI:10.5339/avi.2025.2]

- Sarkar J, Sarkar C. Study of role of internet access and frontline workers in community-based child nutrition programs for budget allocation of national health services. Caspian J Health Res. 2024; 9(4):225-36. [DOI:10.32598/CJHR.9.4.1694.1]

Article Type: Original Contributions |

Subject:

Health Education and Promotion

Received: 2025/06/12 | Accepted: 2025/08/15 | Published: 2025/10/1

Received: 2025/06/12 | Accepted: 2025/08/15 | Published: 2025/10/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |