Volume 10, Issue 4 (10-2025)

CJHR 2025, 10(4): 275-282 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR. GUMS. REC.1400.007

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rouhani-Tonekaboni N, Niksirat S, Kasmaei P. Socioeconomic Characteristics and perceived response cost in Prevention and Control of COVID-19 among Health Care Providers. CJHR 2025; 10 (4) :275-282

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-431-en.html

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-431-en.html

1- Department of Health Education and Promotion, Health and Environment Research Center, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. , rouhani.phd@gmail.com

2- Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

3- Department of Health Education and Promotion, Health and Environment Research Center, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

2- Department of Health Education and Promotion, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran

3- Department of Health Education and Promotion, Health and Environment Research Center, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

Keywords: Socioeconomic Characteristics, Cost, Prevention and Control, COVID-19, Health Care Providers

Full-Text [PDF 512 kb]

(96 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (369 Views)

Full-Text: (41 Views)

Introduction

The spread of infectious diseases is a significant public health problem [1]. The rate of transmission of coronavirus disease is extremely rapid, although the majority of cases of the disease cause mild symptoms [2]. The interval between exposure to the disease and the appearance of symptoms is 2 to 14 days [3].

The highly contagious nature of COVID-19 facilitates its rapid spread, leading to epidemics and increased mortality [4]. Therefore, government urgent activities such as emergency treatment of patients, quarantine of suspected and confirmed cases, protection of HCPs, and public health interventions are essential [5]. Controlling and suppressing coronavirus in a community requires identifying, treating, and isolating infected cases, as well as tracing and quarantining close contacts of patients, which increases the likelihood of HCPs becoming infected with the disease [5].

HCPs have direct contact with patients infected with coronavirus and healthy people [6]. Therefore, preventive activities by them to protect themselves against this disease are one of the most important and essential strategies in the prevention and control program against respiratory viral diseases in the community [7]. Preventive activities such as education, awareness raising, and preventive skills for HCPs protection against this disease are one of the most essential strategies of the COVID-19 disease prevention and control program. To identify preventive activities and control viral diseases, the determinants and effective factors of preventive behaviors against respiratory viral diseases must be identified [8]. Behavior change can be achieved through health education, which serves as the cornerstone of all health activities [9]. The greatest success in health behavior promotion programs is achieved when, in addition to recognizing the current situation, factors affecting individual behavior are also considered [10]. Awareness must lead to the creation of appropriate beliefs, and the necessary facilities and conditions must be available to create behavior; in other words, there must be no obstacles in the way of behavior. Therefore, health strategies should be able to identify perceived response cost (PRC) and take appropriate actions to decrease it. The concept of PRC refers to an individual’s perceptions of the potentially negative aspects of performing a behavior, such as cost, risk, unavailability, and time, which act as barriers to performing the behavior [11, 12]. The PRC refers to beliefs about the real or perceived costs of pursuing a behavior. An individual may believe that a new behavior will be effective in reducing the perceived sensitivity or severity of a disease, while also viewing the behavior as costly, difficult, unpleasant, painful, or distressing [13]. Health educators need to reduce these costs to the point where the person adopts the suggested behaviors [14].

Several studies have examined PRC to COVID-19 preventive behaviors [7, 15, 16] where the average PRC score was reported to be moderate. Evidence shows that the spread of COVID-19 is increasing in the country, and a significant number of HCPs are working in the healthcare system. Factors such as the lack of sufficient knowledge and correct beliefs about protective behaviors among HCPs, occupational exposure to risk factors in healthcare centers, make it necessary to conduct studies on beliefs in preventive behaviors; by understanding the beliefs among HCPs in comprehensive health service centers in Gilan Province, the results can be used to design educational interventions to modify beliefs and promote preventive behaviors against COVID among HCPs. Therefore, the current study was designed to identify the socioeconomic factors associated with PRC toward coronavirus prevention among HCPs in in Gilan province, northern Iran.

Material and Methods

Study design and participants

A descriptive study was conducted on 346 HCPs in Gilan province during May-June 2021. The sample was selected using a multistage cluster random sampling method. In the first stage, the clusters were defined as the five geographical regions of Gilan Province i.e. north, south, center, east, and west. In the second stage, one to two cities were randomly selected from each geographical region. The selected cities included Anzali, Rudbar, Rasht, Lahijan, Langerud, Samsara, Shaft, and Astara. In the third stage, simple random sampling was performed within each selected city from a list of healthcare professionals, in proportion to the number of healthcare personnel. Inclusion criteria of the study included all health care providers in Gilan province who agreed to participate in the study. Individuals on leave for over four months during the assessment period and those with incomplete questionnaires were excluded from the study.

Instruments

Data collection tools was a researcher‐designed questionnaire consisting of two section. The first section included demographic characteristics and health condition. In this section, healthcare professionals assessed their own health condition based on their opinion using four categories: Poor, moderate, good, and excellent. The next section of questionnaire assessed PRC construct using five items rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A higher score indicated that HCPs perceived more barriers to performing preventive behavior. Questionnaire inspired by some studies conducted by Bashirian et al. [7] and Farooq et al. [17] with subsequent revisions made by the research team. The content validity of the questionnaire was assessed by nine experts in health education and health promotion, epidemiology, and biostatistics. After removing and correcting some questions, the mean values of CVR and CVI of the PRC construct were 0.95 and 1, respectively. The reliability of the scale was evaluated by administering the questionnaire to 20 healthcare professionals outside the main study sample. The internal consistency of the items assessed based on Cronbach’s α was 0.71.

Procedure

An online questionnaire was prepared using the Porsline platform, and the link was distributed to healthcare personnel via SMS. The participants completed the questionnaire within 10-15 minutes after studying the objectives of the study and making sure of the confidentiality of their information.

Statistical analysis

Data were described in terms of frequency and percent. Normality assumption of the PRC score was evaluated using skewness and kurtosis indices and graphical visualization of data. The groups were compared using independent t-test or analysis of variance. Post-hoc analysis using the least square difference was employed for pairwise comparison. The independent association of demographic variables with the PRC score was evaluated using multiple linear regression analysis. Statistical analysis was performed in Stata software, version 14. A P<0.05 was considered as significant. All statistical analysis was carried out in SPSS software, version 22.

Results

Fifty-seven percent of health care providers were 40 to 60‐year‐old. The majority were women (86%) and married (76.6%). Among the participants, 79% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Nearly half of them (44.5%) reported a monthly income between 300 and 450 USD, and the majority (93.1%) lived in urban areas. In addition, 62% did not have any systemic diseases, and 60% described their health status as good. Furthermore, 40.4% of the participants, or their relatives, had been exposed to coronavirus.

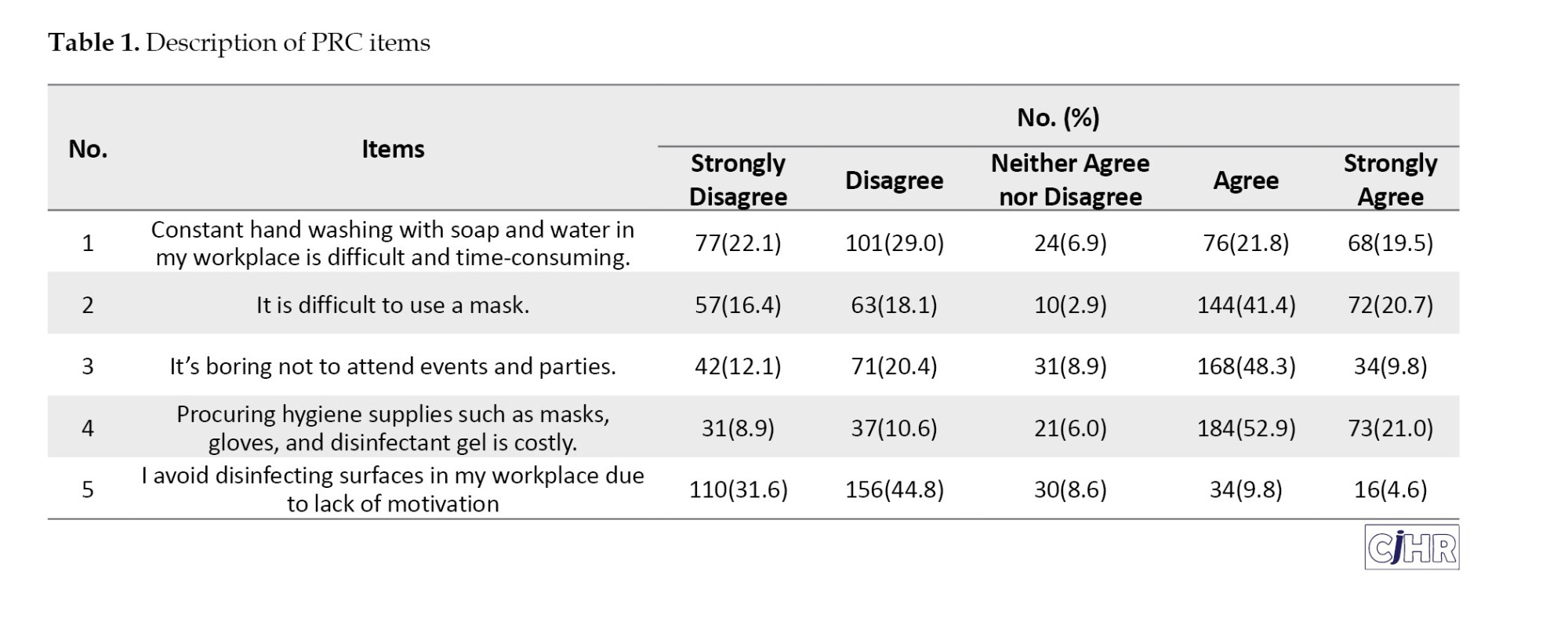

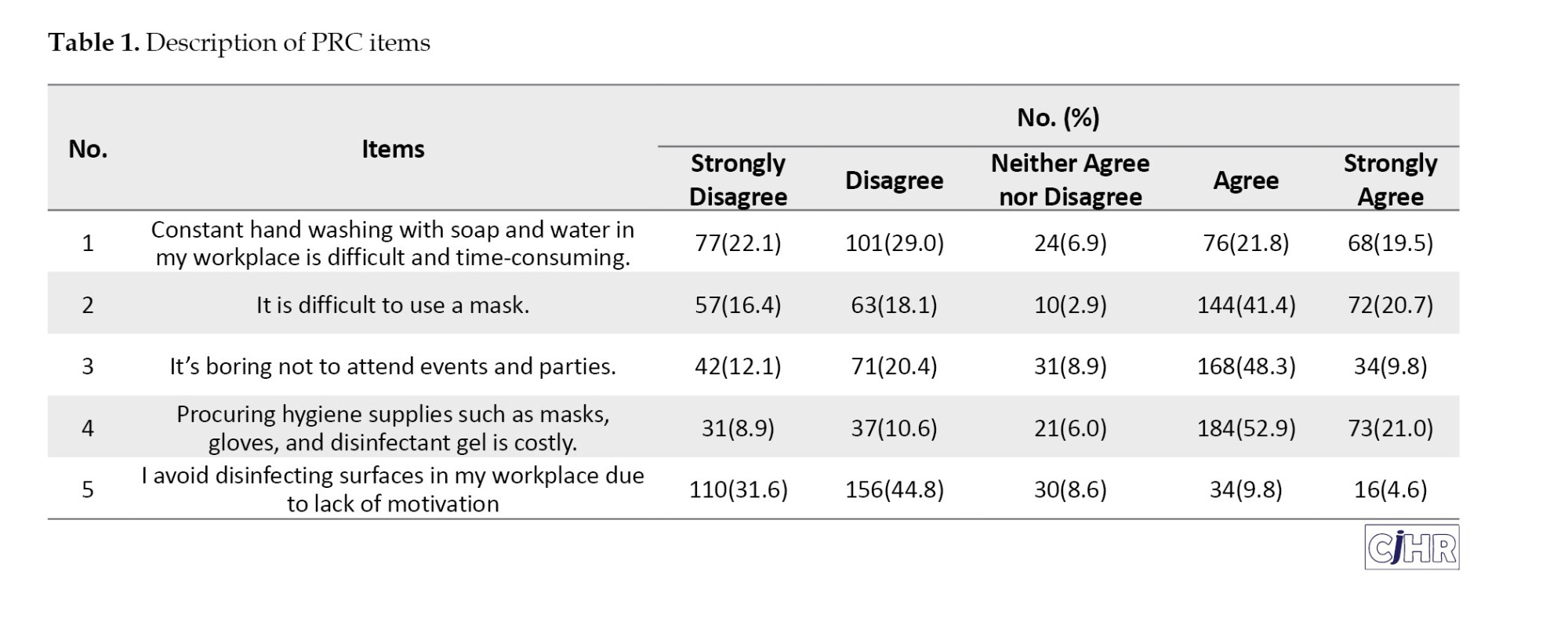

The Mean±SD of the PRC score was 15.20±4.26, and the average percentage of the maximum obtainable score was 51%. Among the PRC items, the highest PRC was for the item “ procuring hygiene supplies such as masks, gloves, and disinfectant gel is costly.” with 73.9% agreeing with it. The lowest PRC was for the item “ I don’t feel like disinfecting surfaces in my workplace.” with 14.4% agreement (Table 1).

A significant relationship observed between demographic variables of age group (P=0.001), level of education (P=0.029), job status (P=0.023), Health condition (P=0.002), history of chronic diseases (P=0.03) and the PRC score. So that the participants who had a history of chronic disease felt more costs. Also, the results of post hoc analysis showed that the mean of the PRC in participants older than 50 years old was significantly lower than the other age-groups. Participants with master degree of education had significantly higher score in the PRC compared to bachelor level of education. The difference between other educational levels was not statistically significant. Moderate status of health had higher mean score of the PRC that was significantly different from good and excellent status of health. Participants who had temporary job status had significantly higher mean score of the PRC (Table 2).

In the multiple linear regression model, the variables of age, educational level, and disease history were independently associated with the PRC. The mean score of the PRC construct in individuals over 50 years old was 3.13-point lower than individuals aged 20 to 30 years. Individuals with a master’s degree had a 2.05-point higher PRC score than those with a diploma. Additionally, the PRC score in individuals with a history of COVID was 0.96 units higher than in those without such a history (Table 3).

Discussion

Given the high prevalence of COVID-19 and its contagiousness, it is important to adhere to personal protection protocols for disease control and prevention. One of the most important groups at risk are HCPs. Therefore, taking preventive behaviors to protection against this disease is one of the most important and essential strategies in the prevention and control against respiratory viral diseases [18]. Costs against adopting recommended preventive behaviors are factors that is measured by the social costs, money, personal costs, time and effort. Increasing the cost of adopting recommended health behaviors reduces the intention to perform the behaviors [19].

In the present study, the average percentage of the PRC was observed to be moderate (51%). This finding is consistent with the study by Mortada et al. [20] that assessed COVID-19 preventive health behaviors of healthcare providers (HCPs) and then determined behavioral determinants using protection motivation theory in Saudi Arabia.

While this study is inconsistent with the study by Farooq et al. [17] which investigated the effect of online information on self-quarantine intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic in Finland. The reason for this can be attributed to the similarity of the population of the present study with that of Mortada et al. [20]. While Farooq’s study [18] examined the general population, which is different from the population of HCPs in the present study. The perception of the studied individual about the costs of COVID-preventive behaviors was found to be moderate in the study by Bashirian et al. [7] that examined factors related to COVID-19 preventive behaviors in hospital employees. In the study by Limkunakul et al. [21] the PRC to COVID-19 prevention behaviors among hospital staff was also moderate.

In the current study, the most important PRC was the high cost of purchasing hygiene products (73.9%) followed by the difficulty of using masks (62.1%). A limited number of studies in the existing literature have assessed individual items of PRCs (barriers) associated with COVID-19 preventive behaviors. In the study by Karimi and Niknami [22] who assessed self-efficacy and perceived benefits/barriers on the AIDs preventive behaviors, one of the most important perceived barriers was lack of accessible and free testing centers.

While, in a study by Wibowo et al. [23] who examined barriers and facilitators of preventive behaviors against COVID-19, optimism was reported as a barrier to preventive behaviors among people who did not follow these behaviors.

In the present study, older people perceived fewer costs and challenges to COVID-19 prevention behaviors. The reason for this finding could be that individuals over 50 years of age tend to feel more vulnerable and sensitive to illnesses and physical problems due to being middle-aged. They may perceive themselves as more likely to be exposed to diseases because of their advancing age. Consequently, they consider obstacles and challenges to be less significant and make greater efforts to overcome them. For this reason, they are more likely to engage in self-protective behaviors against diseases.

The findings of the current study showed that participants with a master’s degree had a 2.05-point higher PRC score than those with a diploma. Educated individuals are often busier with work responsibilities, experience time constraints, and feel more fatigue and boredom, which may lead them to perceive greater costs and challenges in adopting health-promoting behaviors. This finding is in contrast with previous report by Fuller et al. [24] who found that the probability of barriers was higher for people with lower education. The reason for this difference can be attributed to the difference in the population studied in the present study and the aforementioned study.

In the present study, the PRC score among individuals with a history of COVID-19 was 0.96 points higher than among those without such a history. This finding may be explained by the fact that individuals who have previously contracted COVID-19 may have developed certain unhealthy habits or behavioral patterns that persisted after recovery. Consequently, they may perceive greater obstacles or barriers to engaging in health-promoting behaviors.

Becker et al. (1974) believes that perceived barriers are the most important contributor to the behavior change. Perceived barriers refer to beliefs about the real and perceived costs of pursuing a new behavior. An individual may believe that a new behavior will be effective in reducing the perceived risk of being involved in a disease or its severity, but may perceive the action as costly, inappropriate, uncomfortable, painful, or annoying [25]. Health educators must reduce these barriers so that the individual can take the recommended actions. They can do this by providing reassurance, correcting misunderstandings, and providing incentives [14]. Health policymakers and planners should pay attention to reducing perceived barriers, because individuals’ perceptions of costs and barriers can act as barriers to preventive behaviors, and people may perform risky behaviors despite being aware of them.

One of the limitations of this study was the data collection method, which relied on self-reported questionnaires. This approach may have introduced response bias. To minimize this limitation, the questionnaires were completed anonymously. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study objectives were clearly explained at the beginning of the questionnaire. Participants were also encouraged to respond to the questions as accurately and honestly as possible.

Conclusion

The present study found that the PRC of performing COVID-19 prevention behavior was moderate. This factor was significantly associated with age, education, and disease history. Educational interventions should be designed and implemented to reduce the response cost in the study population. Educational interventions should focus more on younger individuals, those with higher levels of education and work commitments, and those with a history of illness. To moderate the response cost, it is useful to reassure individuals that performing the behavior will incur few costs, correct any misconceptions, and provide incentives for the individual to engage in the behavior. One of the educational methods used to moderate response costs is the brainstorming method, in which participants discuss their perceived costs and then suggest ways to reduce them.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Code: IR. GUMS. REC.1400.007).

Funding

Research financial support carried out by Deputy of Research and Technology Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and data analysis: Nooshin Rouhani-Tonekaboni; Supervision, review & editing: Parisa Kasmaei; Data collection: Souri Niksirat; Writing the original draft: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors stated no conflict of interest

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the healthcare providers that participate in the study and the appreciate personnel of the health center of Gilan Province who patiently cooperated to authors toward collecting the necessary data.

References

The spread of infectious diseases is a significant public health problem [1]. The rate of transmission of coronavirus disease is extremely rapid, although the majority of cases of the disease cause mild symptoms [2]. The interval between exposure to the disease and the appearance of symptoms is 2 to 14 days [3].

The highly contagious nature of COVID-19 facilitates its rapid spread, leading to epidemics and increased mortality [4]. Therefore, government urgent activities such as emergency treatment of patients, quarantine of suspected and confirmed cases, protection of HCPs, and public health interventions are essential [5]. Controlling and suppressing coronavirus in a community requires identifying, treating, and isolating infected cases, as well as tracing and quarantining close contacts of patients, which increases the likelihood of HCPs becoming infected with the disease [5].

HCPs have direct contact with patients infected with coronavirus and healthy people [6]. Therefore, preventive activities by them to protect themselves against this disease are one of the most important and essential strategies in the prevention and control program against respiratory viral diseases in the community [7]. Preventive activities such as education, awareness raising, and preventive skills for HCPs protection against this disease are one of the most essential strategies of the COVID-19 disease prevention and control program. To identify preventive activities and control viral diseases, the determinants and effective factors of preventive behaviors against respiratory viral diseases must be identified [8]. Behavior change can be achieved through health education, which serves as the cornerstone of all health activities [9]. The greatest success in health behavior promotion programs is achieved when, in addition to recognizing the current situation, factors affecting individual behavior are also considered [10]. Awareness must lead to the creation of appropriate beliefs, and the necessary facilities and conditions must be available to create behavior; in other words, there must be no obstacles in the way of behavior. Therefore, health strategies should be able to identify perceived response cost (PRC) and take appropriate actions to decrease it. The concept of PRC refers to an individual’s perceptions of the potentially negative aspects of performing a behavior, such as cost, risk, unavailability, and time, which act as barriers to performing the behavior [11, 12]. The PRC refers to beliefs about the real or perceived costs of pursuing a behavior. An individual may believe that a new behavior will be effective in reducing the perceived sensitivity or severity of a disease, while also viewing the behavior as costly, difficult, unpleasant, painful, or distressing [13]. Health educators need to reduce these costs to the point where the person adopts the suggested behaviors [14].

Several studies have examined PRC to COVID-19 preventive behaviors [7, 15, 16] where the average PRC score was reported to be moderate. Evidence shows that the spread of COVID-19 is increasing in the country, and a significant number of HCPs are working in the healthcare system. Factors such as the lack of sufficient knowledge and correct beliefs about protective behaviors among HCPs, occupational exposure to risk factors in healthcare centers, make it necessary to conduct studies on beliefs in preventive behaviors; by understanding the beliefs among HCPs in comprehensive health service centers in Gilan Province, the results can be used to design educational interventions to modify beliefs and promote preventive behaviors against COVID among HCPs. Therefore, the current study was designed to identify the socioeconomic factors associated with PRC toward coronavirus prevention among HCPs in in Gilan province, northern Iran.

Material and Methods

Study design and participants

A descriptive study was conducted on 346 HCPs in Gilan province during May-June 2021. The sample was selected using a multistage cluster random sampling method. In the first stage, the clusters were defined as the five geographical regions of Gilan Province i.e. north, south, center, east, and west. In the second stage, one to two cities were randomly selected from each geographical region. The selected cities included Anzali, Rudbar, Rasht, Lahijan, Langerud, Samsara, Shaft, and Astara. In the third stage, simple random sampling was performed within each selected city from a list of healthcare professionals, in proportion to the number of healthcare personnel. Inclusion criteria of the study included all health care providers in Gilan province who agreed to participate in the study. Individuals on leave for over four months during the assessment period and those with incomplete questionnaires were excluded from the study.

Instruments

Data collection tools was a researcher‐designed questionnaire consisting of two section. The first section included demographic characteristics and health condition. In this section, healthcare professionals assessed their own health condition based on their opinion using four categories: Poor, moderate, good, and excellent. The next section of questionnaire assessed PRC construct using five items rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A higher score indicated that HCPs perceived more barriers to performing preventive behavior. Questionnaire inspired by some studies conducted by Bashirian et al. [7] and Farooq et al. [17] with subsequent revisions made by the research team. The content validity of the questionnaire was assessed by nine experts in health education and health promotion, epidemiology, and biostatistics. After removing and correcting some questions, the mean values of CVR and CVI of the PRC construct were 0.95 and 1, respectively. The reliability of the scale was evaluated by administering the questionnaire to 20 healthcare professionals outside the main study sample. The internal consistency of the items assessed based on Cronbach’s α was 0.71.

Procedure

An online questionnaire was prepared using the Porsline platform, and the link was distributed to healthcare personnel via SMS. The participants completed the questionnaire within 10-15 minutes after studying the objectives of the study and making sure of the confidentiality of their information.

Statistical analysis

Data were described in terms of frequency and percent. Normality assumption of the PRC score was evaluated using skewness and kurtosis indices and graphical visualization of data. The groups were compared using independent t-test or analysis of variance. Post-hoc analysis using the least square difference was employed for pairwise comparison. The independent association of demographic variables with the PRC score was evaluated using multiple linear regression analysis. Statistical analysis was performed in Stata software, version 14. A P<0.05 was considered as significant. All statistical analysis was carried out in SPSS software, version 22.

Results

Fifty-seven percent of health care providers were 40 to 60‐year‐old. The majority were women (86%) and married (76.6%). Among the participants, 79% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Nearly half of them (44.5%) reported a monthly income between 300 and 450 USD, and the majority (93.1%) lived in urban areas. In addition, 62% did not have any systemic diseases, and 60% described their health status as good. Furthermore, 40.4% of the participants, or their relatives, had been exposed to coronavirus.

The Mean±SD of the PRC score was 15.20±4.26, and the average percentage of the maximum obtainable score was 51%. Among the PRC items, the highest PRC was for the item “ procuring hygiene supplies such as masks, gloves, and disinfectant gel is costly.” with 73.9% agreeing with it. The lowest PRC was for the item “ I don’t feel like disinfecting surfaces in my workplace.” with 14.4% agreement (Table 1).

A significant relationship observed between demographic variables of age group (P=0.001), level of education (P=0.029), job status (P=0.023), Health condition (P=0.002), history of chronic diseases (P=0.03) and the PRC score. So that the participants who had a history of chronic disease felt more costs. Also, the results of post hoc analysis showed that the mean of the PRC in participants older than 50 years old was significantly lower than the other age-groups. Participants with master degree of education had significantly higher score in the PRC compared to bachelor level of education. The difference between other educational levels was not statistically significant. Moderate status of health had higher mean score of the PRC that was significantly different from good and excellent status of health. Participants who had temporary job status had significantly higher mean score of the PRC (Table 2).

In the multiple linear regression model, the variables of age, educational level, and disease history were independently associated with the PRC. The mean score of the PRC construct in individuals over 50 years old was 3.13-point lower than individuals aged 20 to 30 years. Individuals with a master’s degree had a 2.05-point higher PRC score than those with a diploma. Additionally, the PRC score in individuals with a history of COVID was 0.96 units higher than in those without such a history (Table 3).

Discussion

Given the high prevalence of COVID-19 and its contagiousness, it is important to adhere to personal protection protocols for disease control and prevention. One of the most important groups at risk are HCPs. Therefore, taking preventive behaviors to protection against this disease is one of the most important and essential strategies in the prevention and control against respiratory viral diseases [18]. Costs against adopting recommended preventive behaviors are factors that is measured by the social costs, money, personal costs, time and effort. Increasing the cost of adopting recommended health behaviors reduces the intention to perform the behaviors [19].

In the present study, the average percentage of the PRC was observed to be moderate (51%). This finding is consistent with the study by Mortada et al. [20] that assessed COVID-19 preventive health behaviors of healthcare providers (HCPs) and then determined behavioral determinants using protection motivation theory in Saudi Arabia.

While this study is inconsistent with the study by Farooq et al. [17] which investigated the effect of online information on self-quarantine intentions during the COVID-19 pandemic in Finland. The reason for this can be attributed to the similarity of the population of the present study with that of Mortada et al. [20]. While Farooq’s study [18] examined the general population, which is different from the population of HCPs in the present study. The perception of the studied individual about the costs of COVID-preventive behaviors was found to be moderate in the study by Bashirian et al. [7] that examined factors related to COVID-19 preventive behaviors in hospital employees. In the study by Limkunakul et al. [21] the PRC to COVID-19 prevention behaviors among hospital staff was also moderate.

In the current study, the most important PRC was the high cost of purchasing hygiene products (73.9%) followed by the difficulty of using masks (62.1%). A limited number of studies in the existing literature have assessed individual items of PRCs (barriers) associated with COVID-19 preventive behaviors. In the study by Karimi and Niknami [22] who assessed self-efficacy and perceived benefits/barriers on the AIDs preventive behaviors, one of the most important perceived barriers was lack of accessible and free testing centers.

While, in a study by Wibowo et al. [23] who examined barriers and facilitators of preventive behaviors against COVID-19, optimism was reported as a barrier to preventive behaviors among people who did not follow these behaviors.

In the present study, older people perceived fewer costs and challenges to COVID-19 prevention behaviors. The reason for this finding could be that individuals over 50 years of age tend to feel more vulnerable and sensitive to illnesses and physical problems due to being middle-aged. They may perceive themselves as more likely to be exposed to diseases because of their advancing age. Consequently, they consider obstacles and challenges to be less significant and make greater efforts to overcome them. For this reason, they are more likely to engage in self-protective behaviors against diseases.

The findings of the current study showed that participants with a master’s degree had a 2.05-point higher PRC score than those with a diploma. Educated individuals are often busier with work responsibilities, experience time constraints, and feel more fatigue and boredom, which may lead them to perceive greater costs and challenges in adopting health-promoting behaviors. This finding is in contrast with previous report by Fuller et al. [24] who found that the probability of barriers was higher for people with lower education. The reason for this difference can be attributed to the difference in the population studied in the present study and the aforementioned study.

In the present study, the PRC score among individuals with a history of COVID-19 was 0.96 points higher than among those without such a history. This finding may be explained by the fact that individuals who have previously contracted COVID-19 may have developed certain unhealthy habits or behavioral patterns that persisted after recovery. Consequently, they may perceive greater obstacles or barriers to engaging in health-promoting behaviors.

Becker et al. (1974) believes that perceived barriers are the most important contributor to the behavior change. Perceived barriers refer to beliefs about the real and perceived costs of pursuing a new behavior. An individual may believe that a new behavior will be effective in reducing the perceived risk of being involved in a disease or its severity, but may perceive the action as costly, inappropriate, uncomfortable, painful, or annoying [25]. Health educators must reduce these barriers so that the individual can take the recommended actions. They can do this by providing reassurance, correcting misunderstandings, and providing incentives [14]. Health policymakers and planners should pay attention to reducing perceived barriers, because individuals’ perceptions of costs and barriers can act as barriers to preventive behaviors, and people may perform risky behaviors despite being aware of them.

One of the limitations of this study was the data collection method, which relied on self-reported questionnaires. This approach may have introduced response bias. To minimize this limitation, the questionnaires were completed anonymously. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study objectives were clearly explained at the beginning of the questionnaire. Participants were also encouraged to respond to the questions as accurately and honestly as possible.

Conclusion

The present study found that the PRC of performing COVID-19 prevention behavior was moderate. This factor was significantly associated with age, education, and disease history. Educational interventions should be designed and implemented to reduce the response cost in the study population. Educational interventions should focus more on younger individuals, those with higher levels of education and work commitments, and those with a history of illness. To moderate the response cost, it is useful to reassure individuals that performing the behavior will incur few costs, correct any misconceptions, and provide incentives for the individual to engage in the behavior. One of the educational methods used to moderate response costs is the brainstorming method, in which participants discuss their perceived costs and then suggest ways to reduce them.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Code: IR. GUMS. REC.1400.007).

Funding

Research financial support carried out by Deputy of Research and Technology Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and data analysis: Nooshin Rouhani-Tonekaboni; Supervision, review & editing: Parisa Kasmaei; Data collection: Souri Niksirat; Writing the original draft: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors stated no conflict of interest

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the healthcare providers that participate in the study and the appreciate personnel of the health center of Gilan Province who patiently cooperated to authors toward collecting the necessary data.

References

- Glass LM, Glass RJ. Social contact networks for the spread of pandemic influenza in children and teenagers. BMC Public Health. 2008; 8:61. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-8-61] [PMID]

- Lai CC, Shih TP, Ko WC, Tang HJ, Hsueh PR. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): The epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020; 55(3):105924. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924] [PMID]

- Hui DS, I Azhar E, Madani TA, Ntoumi F, Kock R, Dar O, ET AL. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health - The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2020; 91:264-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.009] [PMID]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [Internet]. 2020 [Updated 2020 December 1]. Available from: [Link]

- Qian M, Wu Q, Wu P, Hou Z, Liang Y, Cowling BJ, et al. Anxiety levels, precautionary behaviours and public perceptions during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in China: A population-based cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open. 2020; 10(10):e040910. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040910]

- Park JE, Jung S, Kim A, Park JE. MERS transmission and risk factors: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2018; 18(1):574. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-015-1924-x] [PMID]

- Bashirian S, Jenabi E, Khazaei S, Barati M, Karimi-Shahanjarini A, Zareian S, et al. Factors associated with preventive behaviours of COVID-19 among hospital staff in Iran in 2020: an application of the Protection Motivation Theory. J Hosp Infect. 2020; 105(3):430-3. [DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2020.04.035] [PMID]

- Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Cheung T, et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020; 7(3):228-9. [DOI:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8] [PMID]

- Safari M, Shojaeizadeh D. [Theories models and methods of health education and promotion (Persian)]. Tehran: Asar-E Sobhan Publishing; 2009. [Link]

- Rogers RW. Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: A revised theory of protection motivation. In: Cacioppo J, Petty R, editors. Social psychophysiology. New York: Guilford Press; 1983. [Link]

- Galloway RD. Health promotion: Causes, beliefs and measurements. Clin Med Res. 2003; 1(3):249-58. [DOI:10.3121/cmr.1.3.249] [PMID]

- Pender NJ, Murdaugh CL, Parsons MA. Health promotion in nursing practice. London: Pearson; 2010. [Link]

- Rosenstock IM. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health education monographs. 1974; 2(4):328-35. [DOI:10.1177/109019817400200403]

- Sharma M. Theoretical foundations of health education and health promotion. Burlington: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2021. [Link]

- Niksirat S, Rouhani-Tonekaboni N, Shakiba M, Kasmaei P. Preventive behaviors against COVID-19 among health care providers in Iran: A cross-sectional study. Health Sci Rep. 2024; 7(2):e1839. [DOI:10.1002/hsr2.1839] [PMID]

- Delshad Noghabi A, Yoshany N, Mohammadzadeh F, Javanbakht S. [Predictors of COVID-19 preventive behaviors in Iranian population over 15 years old: An application of health belief model (Persian)]. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2020; 30(191):13-21. [Link]

- Farooq A, Laato S, Islam AKMN. Impact of online information on self-isolation intention during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020; 22(5):e19128. [DOI:10.2196/19128] [PMID]

- Ji W, Wang W, Zhao X, Zai J, Li X. Homologous recombination within the spike glycoprotein of the newly identified coronavirus may boost cross- species transmission from snake to human. J Med Virol. 2020; 92(4):433-40. [DOI:10.1002/jmv.25682]

- Norman P, Boer H, Seydel ER. Protection motivation theory. In Conner M, Norman P, editors. Predicting health behaviour: Research and practice with social cognition models. Maidenhead: Open University Press. 2005. [Link]

- Mortada E, Abdel-Azeem A, Al Showair A, Zalat MM. Preventive behaviors towards covid-19 pandemic among healthcare providers in Saudi Arabia using the protection motivation theory. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021; 14:685-694. [DOI:10.2147/RMHP.S289837] [PMID]

- Limkunakul C, Phuthomdee S, Srinithiwat P, Chanthanaroj S, Boonsawat W, Sawanyawisuth K. Factors associated with preventive behaviors for COVID-19 infection among healthcare workers by a health behavior model. Trop Med Health. 2022; 50(1):65. [DOI:10.1186/s41182-022-00454-z] [PMID]

- Karimi M, Niknami S. [Self-efficacy and perceived benefits /barriers on the AIDs preventive behaviors (Persian)]. J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci. 2011; 15:384-92. [Link]

- Wibowo RA, Hartarto RB, Bhattacharjee A, Wardani DTK, Sambodo NP, Santoso Utomo PT, et al. Facilitators and barriers of preventive behaviors against COVID-19 during Ramadan: A phenomenology of Indonesian adults. Front Public Health. 2023; 11:960500. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2023.960500] [PMID]

- Fuller HR, Huseth-Zosel A, Van Vleet B, Carson PJ. Barriers to vaccination among older adults: Demographic variation and links to vaccine acceptance. Aging Health Res. 2024; 4 (1):100176. [DOI:10.1016/j.ahr.2023.100176]

- Becker MH, Drachman RH, Kirscht JP. A new approach to explaining sick-role behavior in low-income populations. Am J Public Health. 1974; 64(3):205-16. [Link]

Article Type: Original Contributions |

Subject:

Health Education and Promotion

Received: 2025/07/8 | Accepted: 2025/08/14 | Published: 2025/10/1

Received: 2025/07/8 | Accepted: 2025/08/14 | Published: 2025/10/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |