Volume 10, Issue 4 (10-2025)

CJHR 2025, 10(4): 247-256 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1404.077

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Talaiyan pour F, Davasaz Irani R. Effectiveness of Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Guilt, Emotion Regulation, and Attachment Style in Women Victims of Domestic Violence. CJHR 2025; 10 (4) :247-256

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-436-en.html

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-436-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. ,rdavasazirani@gmail.com

2- Department of Psychology, Ahv.C., Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz, Iran. ,

Keywords: Domestic violence, Guilt, Emotion regulation, Attachment style, Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy

Full-Text [PDF 557 kb]

(177 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (737 Views)

Full-Text: (270 Views)

Introduction

Domestic violence stands as a grave and pervasive global public health crisis and a severe violation of women’s human rights [1]. Defined by the World Health Organization as any behavior within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological, sexual, or controlling abuse, it encompasses a range of harmful actions including physical and sexual aggression and coercion [2]. The pervasive nature of domestic violence is underscored by global statistics revealing that approximately one in three women worldwide experience physical or sexual violence from an intimate partner or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime [3]. Alarmingly, in Iran, an estimated 66% of Iranian women report experiencing domestic violence during their married lives [4]. The profound and multifaceted impact of such destructive experiences on women extends beyond immediate physical harm, leading to a complex array of psychological, emotional, and cognitive challenges, often manifesting as post-traumatic symptoms, mood disturbances, and significant alterations in self-perception and relational patterns [5].

Experiences of severe trauma, such as domestic violence, expose women to a cascade of psychological difficulties, including profound alterations in their emotional states, behaviors, and thought processes [6]. A salient and often debilitating consequence is the pervasive feeling of guilt. Guilt, in this context, frequently arises when the traumatic event conflicts with an individual’s core life rules and moral values, leading to self-blame and a sense of responsibility for the abuse they endured [7]. This moral injury can become deeply entrenched, exacerbated by societal and cultural narratives that sometimes inadvertently place blame on the victim [8]. Chronic guilt can severely impede recovery, fostering feelings of unworthiness and perpetuating a cycle of self-criticism, ultimately diminishing an individual’s capacity for healing and adaptive functioning. The persistence of guilt is a significant barrier to rebuilding self-esteem and moving forward from the traumatic experience [9].

Another critical consequence of domestic violence is impaired emotion regulation [10]. Emotion regulation refers to an individual’s ability to identify, process, manage, and modulate their emotions in an adaptive manner, employing both cognitive and behavioral strategies to navigate stressful situations and respond appropriately to negative emotions such as anger, anxiety, or sadness [11]. Women who have endured domestic violence often struggle with dysregulation, oscillating between emotional suppression and explosive outbursts, or experiencing heightened states of anxiety and depression [12]. This impairment can lead to impulsive reactions, emotional avoidance, and increased vulnerability to psychological disorders, further hindering their ability to form healthy relationships and cope with daily stressors [13]. Effective emotion regulation is crucial for resilience, psychological well-being, and adaptive interpersonal functioning.

Furthermore, domestic violence profoundly impacts an individual’s attachment style [14]. Attachment styles, forged in early childhood through interactions with primary caregivers, dictate how individuals form and maintain emotional bonds throughout their lives, extending from family to friends and intimate partners [15]. Exposure to chronic trauma, such as domestic violence, often reinforces insecure attachment patterns, specifically anxious and avoidant styles [16]. Anxious attachment is characterized by a persistent fear of abandonment, excessive need for validation, and hypersensitivity to relational conflicts, often leading to clingy or desperate behaviors. Conversely, avoidant attachment manifests as emotional distancing, distrust of others, and suppression of attachment needs, typically adopted as a defense mechanism against repeated trauma [17]. Both insecure styles impede the formation of secure, trusting relationships and perpetuate cycles of relational distress, highlighting the critical need for interventions that address these deeply rooted patterns.

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) is a structured, evidence-based psychotherapy specifically designed to address the multifaceted needs of individuals affected by traumatic experiences, including domestic violence [18]. TF-CBT is a well-established therapeutic approach widely recognized for its efficacy in supporting individuals who have experienced trauma, such as physical abuse or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [19]. This evidence-based intervention integrates cognitive and behavioral techniques to address and modify maladaptive thought patterns, alleviate trauma-related symptoms—including guilt, shame, and anxiety—and enhance emotional regulation skills [20]. TF-CBT assists survivors in reframing unhelpful beliefs about themselves and others, reducing avoidant behaviors, and building resilience to manage distressing emotions effectively [21]. Research consistently demonstrates its effectiveness in reducing symptoms of PTSD and depression, while also improving self-efficacy and enhancing overall quality of life, particularly among women survivors [22, 23].

Given the high prevalence of domestic violence against women and its profound psychological repercussions, including chronic guilt, dysregulated emotions, and insecure attachment patterns, this research holds significant importance. Many victims face substantial barriers, such as cultural stigma and limited access to specialized services, while existing interventions often fail to adequately address the specific psychological needs of this vulnerable group. By focusing on the effectiveness of TF-CBT as a targeted approach, this study seeks to fill a critical gap in the Iranian research literature, providing scientific evidence for culturally adapted treatment protocols and supportive policies within welfare and social emergency centers. Furthermore, simultaneously examining the impact on guilt, emotion regulation, and attachment style offers a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms of recovery in this population, representing a notable innovation in trauma psychology. Therefore, the present study aims to answer the question: Is TF-CBT effective in reducing guilt, improving emotion regulation, and modifying attachment styles in women victims of domestic violence at the Ahvaz Welfare Center?

Materials and Methods

This study employed a quasi-experimental design, specifically a pre-test/post-test approach with a control group, to investigate the effectiveness of TF-CBT. The statistical population for this research included all women victims of domestic violence who sought assistance at the Ahvaz Welfare Center in 2024, totaling approximately 150 referrals based on center records. From this population, a convenience sample of 33 participants was carefully selected. The sample size was determined based on guidelines by Cohen [24], which recommend a minimum of 15 to 20 participants per group for sufficient statistical power in quasi-experimental designs, assuming a medium to large effect size. The slight difference in group sizes (16 in the experimental group and 17 in the control group) resulted from random assignment and one participant’s withdrawal from the experimental group due to relocation, with no further attrition observed. Participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (n=16) or the control group (n=17).

Inclusion criteria for participants included women victims of domestic violence presenting to the Ahvaz Welfare Center, aged between 20 and 50 years, demonstrating trauma-related symptoms as per DSM-5 criteria, achieving a score above the mean on the domestic violence questionnaire, possessing at least basic literacy, and expressing willingness to participate in the study without receiving concurrent psychotherapy. Exclusion criteria comprised severe psychiatric disorders (e.g. psychosis, active substance abuse), active suicidal ideation, attendance below 80% of the intervention sessions, and experiencing severe stressful life events during the study period. To encourage participant cooperation and attendance in the context of Ahvaz’s cultural setting, where stigma around mental health and domestic violence is prevalent, strategies such as building trust through initial rapport-building sessions, offering flexible scheduling, and providing culturally sensitive psychoeducation were employed, as recommended by Kazemi Khooban et al. [23]. To control for confounding variables, the study standardized session delivery, ensured facilitator training, and monitored external stressors through regular check-ins, though complete control of variables like prior trauma history was not feasible. Ethical considerations were paramount throughout the research process. All participants provided informed consent, and their confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained. After baseline pre-test assessments for both groups, the experimental group received the intervention, while the control group did not, followed by post-test assessments. Following the conclusion of the study, the control group was offered the intervention in a condensed format.

Measure

Guilt inventory: The guilt inventory, developed by Jones et al. [25], is a 45-item self-report measure designed to assess various aspects of guilt comprehensively. Participants rate their agreement with each statement on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). The scoring ranges for the scales are from 45 to 225. Higher scores on the guilt subscales indicate a greater presence of guilt. Shahmiri et al. [26] reported a Cronbach’s α of 0.74 for the instrument, indicating acceptable internal consistency. For the present study, the Cronbach’s α for the Guilt Inventory was calculated to be 0.82, demonstrating acceptable reliability.

Emotion regulation questionnaire (ERQ): The ERQ, developed by Hofmann and Kashdan [27], is a 20-item self-report measure designed to assess an individual’s habitual use of various emotion regulation strategies. Participants respond using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“not at all true for me”) to 5 (“completely true for me”), with total scores ranging from 20 to 100. Higher scores indicate better emotion regulation abilities. A Persian validation study by Soleimani et al. [28] reported a Cronbach’s α of 0.81, demonstrating good internal consistency. In the present study, the overall Cronbach’s α coefficient for the ERQ was 0.86, further confirming its reliability and validity for use with an Iranian sample.

Experiences in close relationships-revised (ECR-R): The ECR-R, developed by Fraley et al. [29], serves as a robust and widely utilized 36-item self-report measure for assessing adult attachment styles. This scale effectively differentiates between two continuous dimensions of insecure attachment: Anxiety and avoidance. The anxiety subscale, consisting of 18 items, evaluates the degree to which individuals worry about abandonment, rejection, or insufficient responsiveness from close others (e.g. “I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me”). The avoidance subscale, also with 18 items, measures the extent to which individuals feel uncomfortable with closeness and intimacy, preferring self-reliance and emotional distance (e.g. “I feel uncomfortable when others get too close to me”). Participants rate each statement on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). The score range for both the anxiety and avoidance subscales is from 18 to 126. Higher scores on either subscale indicate a greater degree of that specific insecure attachment pattern. In the Iranian standardization study conducted by Pooravari and Fathi Ashtiani [30], the Cronbach’s α coefficient was reported as 0.81, indicating good internal consistency. In the present study, the ECR-R demonstrated strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.87.

Intervention

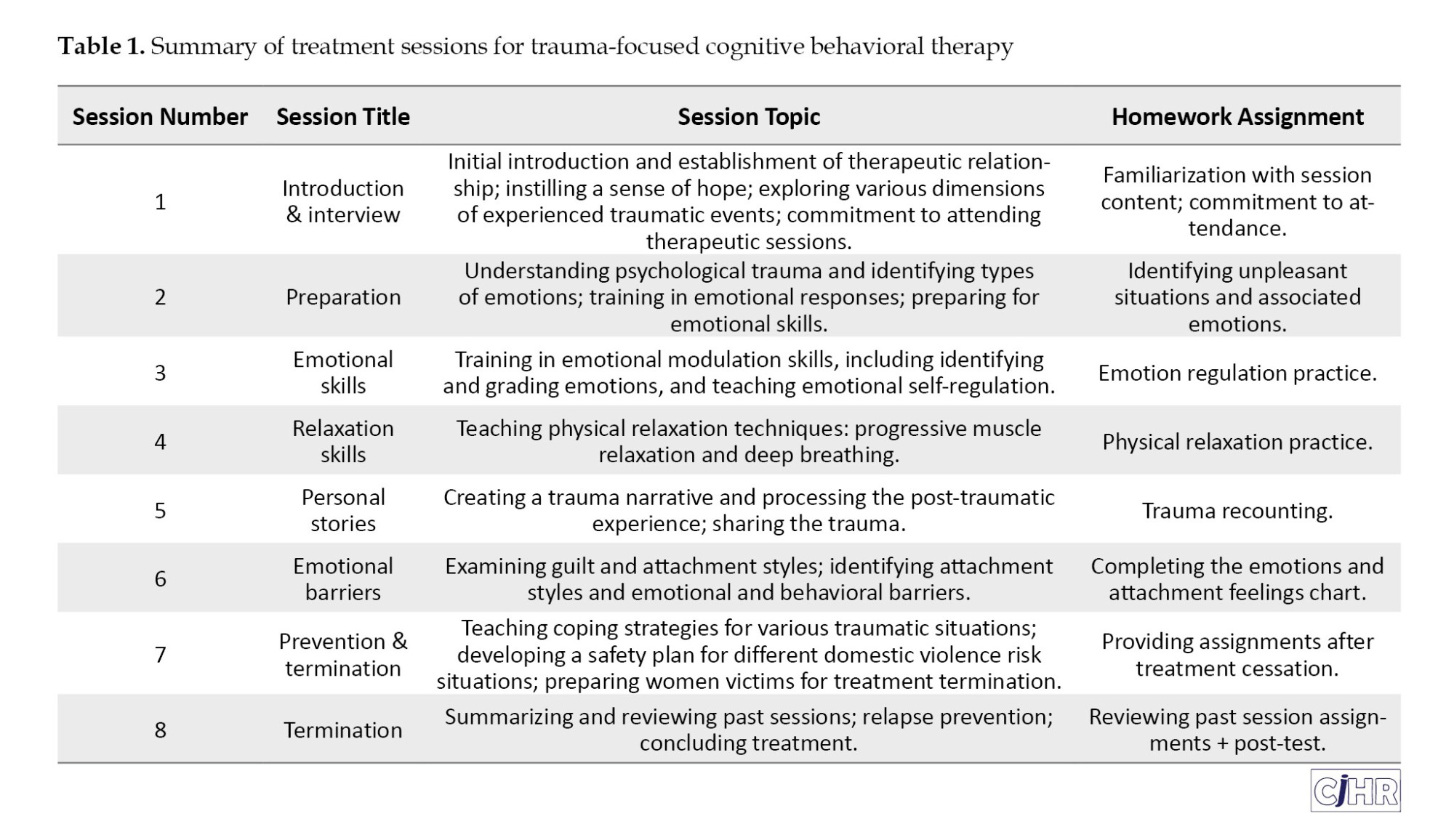

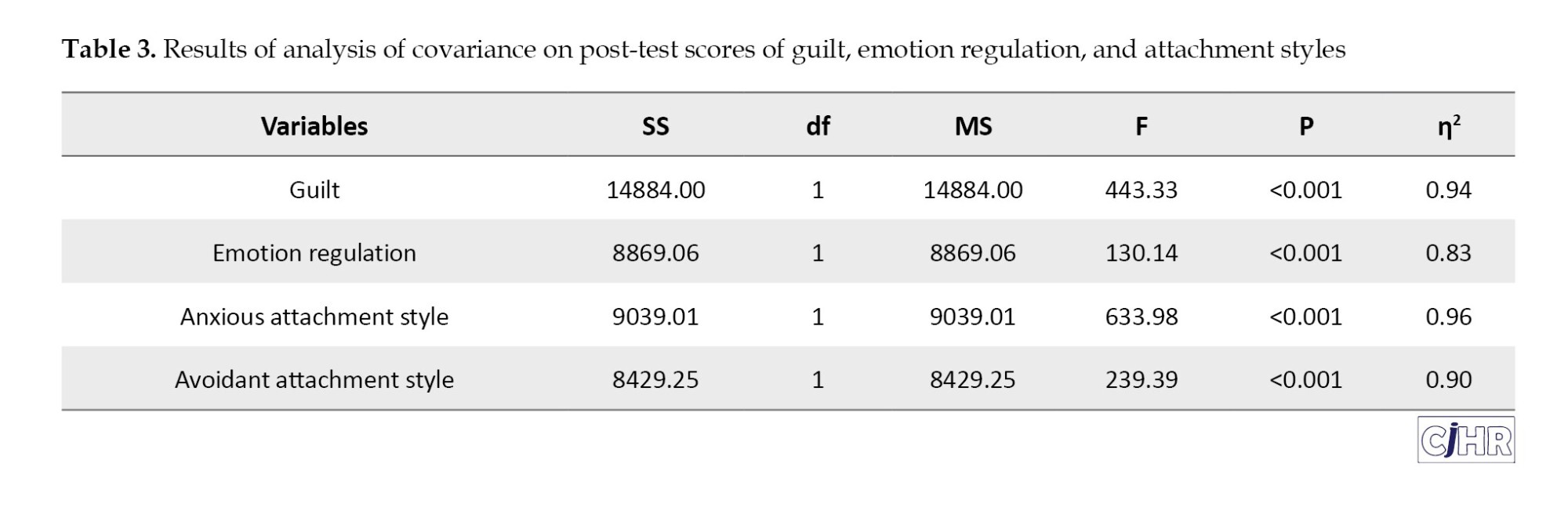

TF-CBT: The TF-CBT intervention, designed based on the structured protocol outlined by Cohen et al. [31], was administered to the experimental group over eight weekly 90-minute sessions. This structured therapy aims to address the multi-faceted impacts of trauma, including guilt, emotion dysregulation, and insecure attachment styles. The sessions systematically guided participants through various therapeutic components, building skills for emotional processing and cognitive restructuring. A summary of the sessions is provided in Table 1, outlining the topic, session title, and homework assignments for each week.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) in SPSS software, version 27. Descriptive statistics, including Mean±SD, and frequency distributions, were calculated for all variables. Prior to conducting the ANCOVA, key statistical assumptions were thoroughly evaluated. Data normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, homogeneity of variances was examined with Levene’s test, homogeneity of regression slopes was verified using an interaction term test between the covariate and the independent variable, and the assumption of linearity between pre-test and post-test scores was checked using scatterplots and Pearson correlation coefficients.

Results

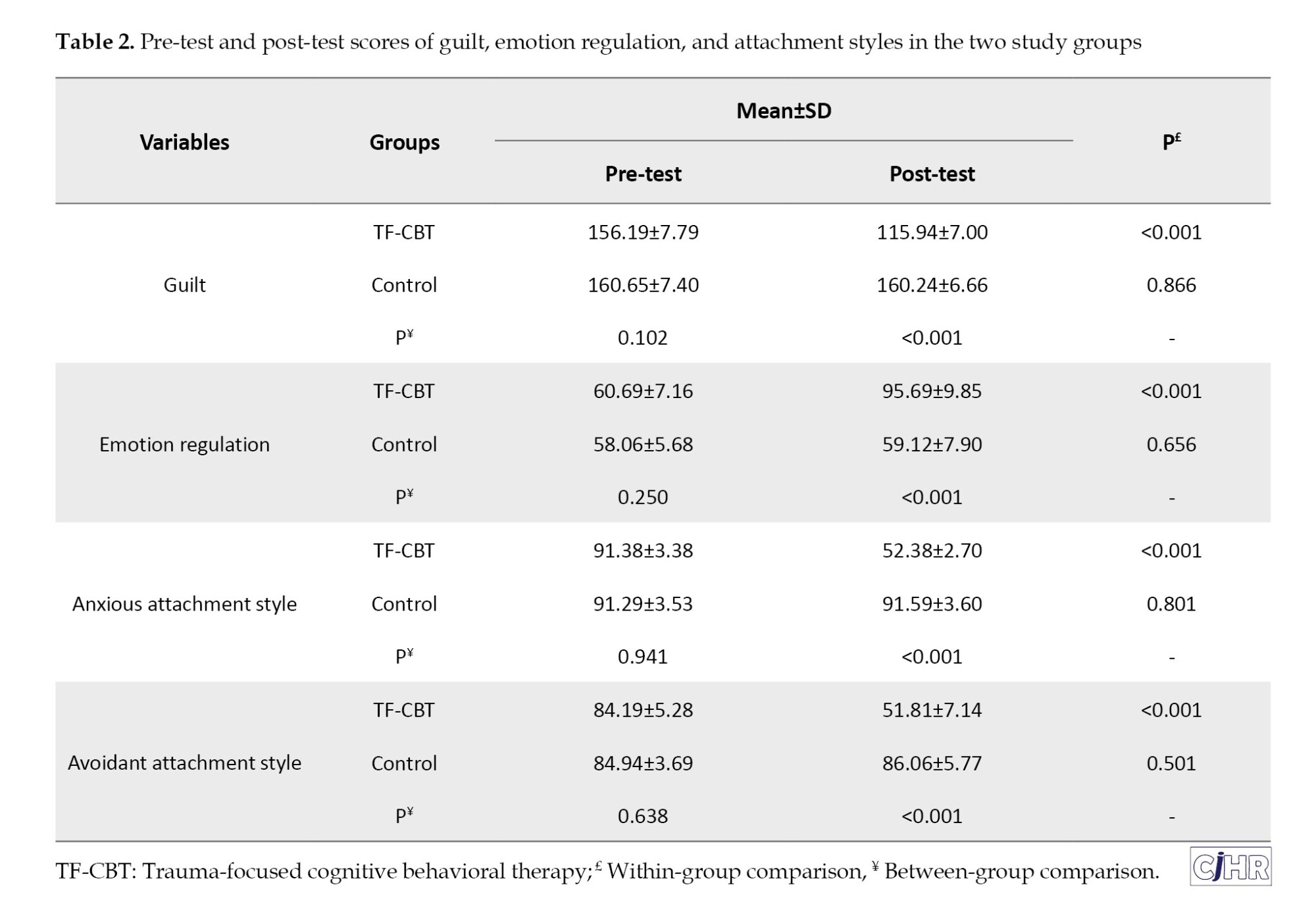

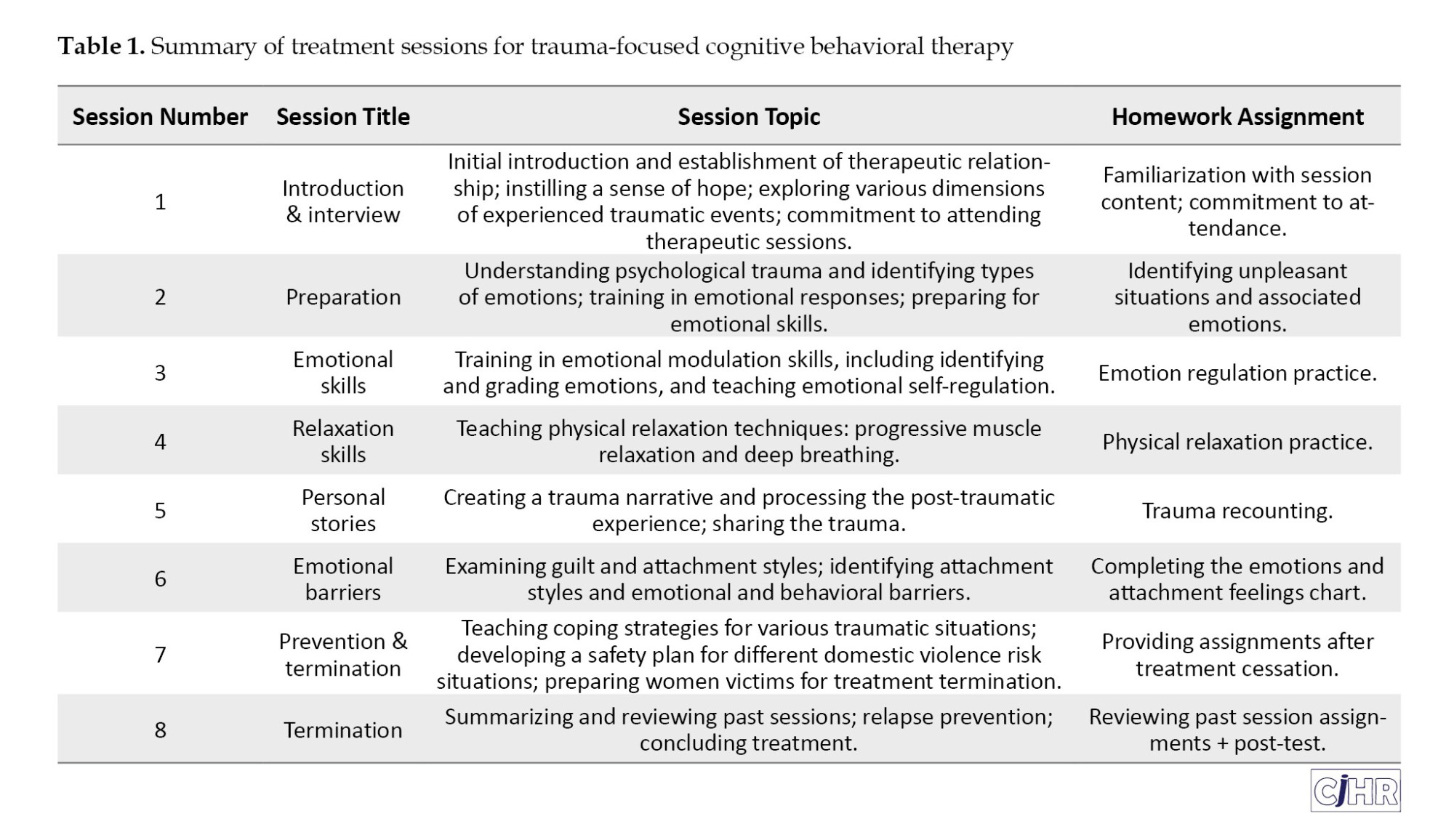

The demographic analysis of the participants revealed that 53% of the subjects were in the age range of 20 to 32 years, while the remaining 47% fell into the 33 to 45-year age bracket. The mean age for the experimental group was 28.29±4.12 years, and for the control group, it was 33.18±5.37 years. This distribution indicates a relatively young adult sample, which is representative of women who may be experiencing domestic violence and seeking support at welfare centers. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics, including Mean±SD, for the research variables (guilt, emotion regulation, and attachment styles) for both the experimental and control groups at pre-test and post-test. Additionally, the table includes the results of within-group (paired t-tests) and between-group (independent t-tests) comparisons for each construct.

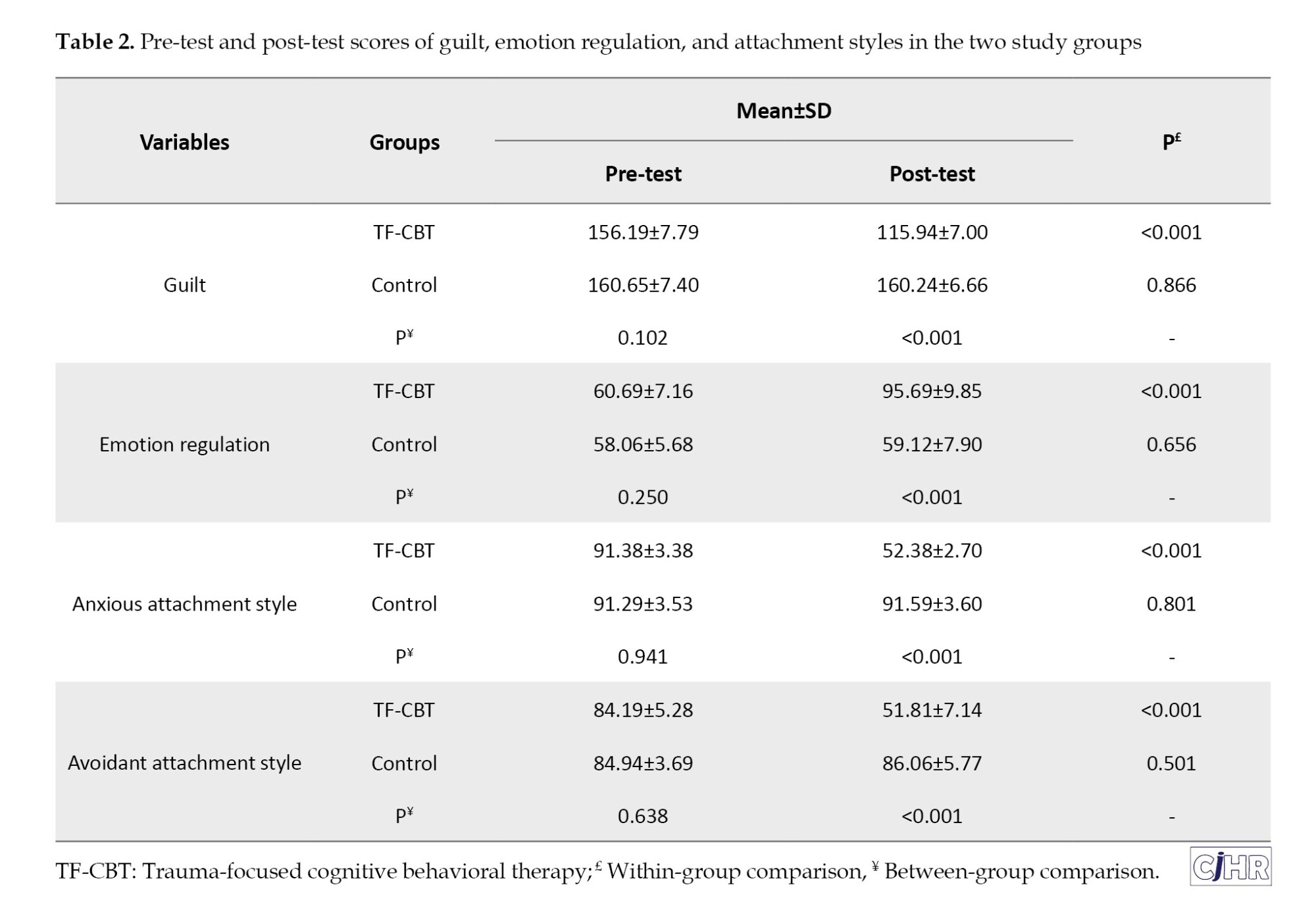

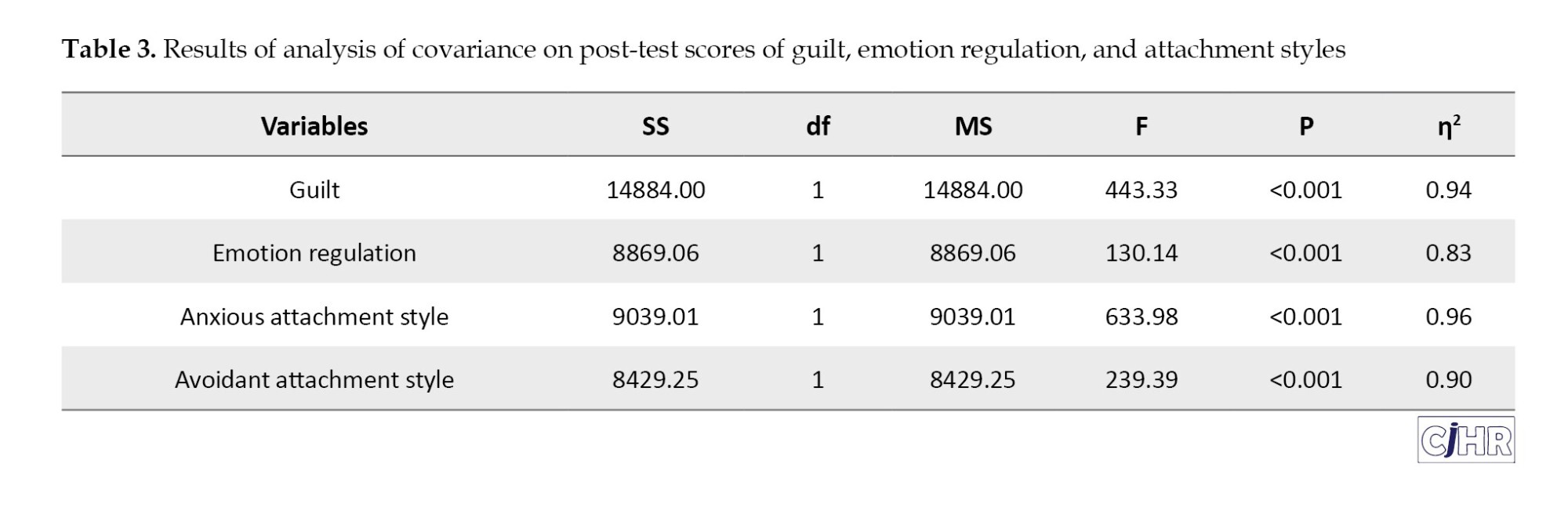

Prior to conducting inferential analyses, the assumption of normality for the data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, with results indicating that the data for all research variables were normally distributed within both the experimental and control groups (all P>0.05). Additional ANCOVA assumptions were evaluated: Homogeneity of variances was confirmed using Levene’s test (all P>0.05), equality of covariance matrices across groups was verified using Box’s M test (P=0.127), and the assumption of sphericity was not applicable as each dependent variable was analyzed separately in univariate ANCOVA models. To determine the effectiveness of TF-CBT on the dependent variables (guilt, emotion regulation, anxious attachment style, and avoidant attachment style) after controlling for pre-test scores, an ANCOVA was performed. Before the ANCOVA, the assumptions of homogeneity of variances, assessed by Levene’s test, and homogeneity of regression slopes were confirmed (all P>0.05). Table 3 presents the results of the ANCOVA, including effect sizes (partial η²).

As shown in Table 3, the results of the ANCOVA revealed a statistically significant effect of TF-CBT on all dependent variables, after controlling for pre-test scores. Specifically, for guilt, there was a significant reduction in post-test scores in the experimental group compared to the control group (F=443.33, P<0.001, η²=0.94). This large effect size suggests a substantial reduction in guilt, with clinical significance indicated by a mean decrease of 40.25 points in the experimental group, surpassing the threshold for meaningful change. Similarly, TF-CBT significantly improved emotion regulation (F=130.14, P<0.001, η²=0.83), indicating a large effect and clinically meaningful improvement, as the experimental group’s mean score increased by 35 points, reflecting enhanced adaptive emotion regulation strategies. Furthermore, the therapy significantly reduced anxious attachment style (F=633.98, P<0.001, η²=0.96) and avoidant attachment style (F=239.39, P<0.001, η²=0.90). These large effect sizes suggest clinically significant shifts toward secure attachment, as post-test scores for both anxious and avoidant subscales in the experimental group fell below the threshold for insecure attachment.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of TF-CBT in addressing key psychological sequelae in women survivors of domestic violence, specifically focusing on guilt, emotion regulation, and insecure attachment styles. The significant findings revealed that TF-CBT profoundly impacted all targeted variables, leading to a substantial reduction in guilt, a marked improvement in emotion regulation abilities, and a significant modification of both anxious and avoidant attachment styles. These results underscore the multidimensional efficacy of TF-CBT as a critical intervention for this vulnerable population.

The observed significant reduction in feelings of guilt among women survivors of domestic violence following TF-CBT aligns robustly with existing literature. This finding resonates with the work of Young et al. [32], who similarly reported that cognitive behavioral approaches are highly effective in alleviating trauma-related guilt. The efficacy can be attributed to TF-CBT’s core principles of cognitive restructuring, which directly challenges distorted cognitions and maladaptive beliefs frequently held by victims, such as self-blame or a sense of responsibility for the abuse endured [21]. By systematically identifying and correcting these ingrained thought patterns, TF-CBT facilitates a healthier reinterpretation of the traumatic events, thereby diminishing the pathological sense of guilt and fostering a more accurate self-perception. Furthermore, the behavioral components of TF-CBT, including gradual exposure to trauma-related memories, enable emotional processing that can alleviate the emotional burden often associated with chronic guilt [32]. This process helps survivors break the cycle of avoidance and integrate the traumatic experience in a less self-condemnatory manner.

Consistent with our findings, TF-CBT demonstrably enhanced emotion regulation capacities in women affected by domestic violence, a result that is in harmony with previous research by Dumornay et al. [33] and Ford et al. [34]. This improvement can be primarily attributed to TF-CBT’s emphasis on teaching adaptive emotional skills. Survivors of repeated trauma often develop maladaptive emotional responses, oscillating between emotional suppression and explosive outbursts [20]. The therapy addresses these dysregulated patterns by providing explicit training in emotion identification, distress tolerance, and cognitive reappraisal, which are vital for managing intense emotional reactions effectively [33]. By correcting distorted cognitive-emotional cycles, where distorted interpretations of events lead to disproportionate emotional responses, TF-CBT equips individuals with robust strategies to modulate their emotions adaptively [18]. Techniques such as controlled exposure to distressing stimuli gradually reduce emotional hypersensitivity, thereby increasing their capacity to manage tension and stress without resorting to maladaptive coping mechanisms [22].

Moreover, the study revealed that TF-CBT significantly modified insecure attachment styles, encompassing both anxious and avoidant dimensions, in women survivors of domestic violence. This outcome is consistent with the findings of Allen and Brown [35], who noted similar positive shifts in attachment patterns through attachment-focused interventions. TF-CBT’s efficacy in this domain stems from its ability to impact deeply ingrained relational schemas that often underpin insecure attachment. For individuals with anxious attachment, the therapy challenges core beliefs like “I cannot survive without a relationship” or “I am to blame for abuse”, fostering a shift toward greater self-reliance and reduced fear of abandonment [16]. Through simulated relational scenarios and assertiveness training, survivors learn to articulate their needs without fearing relational rupture. For those with avoidant attachment, characterized by emotional distancing and distrust, TF-CBT works to reconstruct interpersonal trust and dismantle beliefs such as “trusting others leads to harm”. By facilitating corrective emotional experiences within a safe therapeutic environment and promoting gradual engagement in healthy relationships, the therapy helps survivors build flexible boundaries and develop the capacity for secure attachment without fear of re-traumatization [35].

The comprehensive positive impact of TF-CBT on guilt, emotion regulation, and attachment styles highlights its potential as a holistic intervention for women survivors of domestic violence. These findings contribute significantly to the existing body of knowledge, particularly within the Iranian context, by providing empirical support for targeted, culturally sensitive therapeutic protocols. Integrating TF-CBT into welfare and social emergency centers can offer a pathway towards enhanced psychological well-being, fostering resilience, and promoting the development of healthier interpersonal relationships for this vulnerable population.

Conclusion

Based on the compelling findings of this study, TF-CBT is unequivocally demonstrated as a highly effective intervention for women victims of domestic violence. The significant reductions in guilt, substantial improvements in emotion regulation, and profound modifications of insecure attachment styles highlight TF-CBT’s comprehensive capacity to ameliorate the complex psychological sequelae of intimate partner violence. These results underscore the critical importance of integrating TF-CBT into therapeutic protocols and support services, offering a robust pathway towards fostering resilience, promoting psychological well-being, and enabling healthier relational functioning for this vulnerable population.

Despite its promising results, this study faced certain limitations, including a relatively limited sample size, the inability to control for all potential intervening variables such as the duration and severity of experienced violence, and the lack of a long-term follow-up to assess the sustained effects of the intervention.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was granted ethical approval by the Ethics Committee of the Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz Branch, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1404.077).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Ahvaz Welfare Center for their cooperation and support, and to all the women who participated in this study for their valuable time and trust.

References

Domestic violence stands as a grave and pervasive global public health crisis and a severe violation of women’s human rights [1]. Defined by the World Health Organization as any behavior within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological, sexual, or controlling abuse, it encompasses a range of harmful actions including physical and sexual aggression and coercion [2]. The pervasive nature of domestic violence is underscored by global statistics revealing that approximately one in three women worldwide experience physical or sexual violence from an intimate partner or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime [3]. Alarmingly, in Iran, an estimated 66% of Iranian women report experiencing domestic violence during their married lives [4]. The profound and multifaceted impact of such destructive experiences on women extends beyond immediate physical harm, leading to a complex array of psychological, emotional, and cognitive challenges, often manifesting as post-traumatic symptoms, mood disturbances, and significant alterations in self-perception and relational patterns [5].

Experiences of severe trauma, such as domestic violence, expose women to a cascade of psychological difficulties, including profound alterations in their emotional states, behaviors, and thought processes [6]. A salient and often debilitating consequence is the pervasive feeling of guilt. Guilt, in this context, frequently arises when the traumatic event conflicts with an individual’s core life rules and moral values, leading to self-blame and a sense of responsibility for the abuse they endured [7]. This moral injury can become deeply entrenched, exacerbated by societal and cultural narratives that sometimes inadvertently place blame on the victim [8]. Chronic guilt can severely impede recovery, fostering feelings of unworthiness and perpetuating a cycle of self-criticism, ultimately diminishing an individual’s capacity for healing and adaptive functioning. The persistence of guilt is a significant barrier to rebuilding self-esteem and moving forward from the traumatic experience [9].

Another critical consequence of domestic violence is impaired emotion regulation [10]. Emotion regulation refers to an individual’s ability to identify, process, manage, and modulate their emotions in an adaptive manner, employing both cognitive and behavioral strategies to navigate stressful situations and respond appropriately to negative emotions such as anger, anxiety, or sadness [11]. Women who have endured domestic violence often struggle with dysregulation, oscillating between emotional suppression and explosive outbursts, or experiencing heightened states of anxiety and depression [12]. This impairment can lead to impulsive reactions, emotional avoidance, and increased vulnerability to psychological disorders, further hindering their ability to form healthy relationships and cope with daily stressors [13]. Effective emotion regulation is crucial for resilience, psychological well-being, and adaptive interpersonal functioning.

Furthermore, domestic violence profoundly impacts an individual’s attachment style [14]. Attachment styles, forged in early childhood through interactions with primary caregivers, dictate how individuals form and maintain emotional bonds throughout their lives, extending from family to friends and intimate partners [15]. Exposure to chronic trauma, such as domestic violence, often reinforces insecure attachment patterns, specifically anxious and avoidant styles [16]. Anxious attachment is characterized by a persistent fear of abandonment, excessive need for validation, and hypersensitivity to relational conflicts, often leading to clingy or desperate behaviors. Conversely, avoidant attachment manifests as emotional distancing, distrust of others, and suppression of attachment needs, typically adopted as a defense mechanism against repeated trauma [17]. Both insecure styles impede the formation of secure, trusting relationships and perpetuate cycles of relational distress, highlighting the critical need for interventions that address these deeply rooted patterns.

Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) is a structured, evidence-based psychotherapy specifically designed to address the multifaceted needs of individuals affected by traumatic experiences, including domestic violence [18]. TF-CBT is a well-established therapeutic approach widely recognized for its efficacy in supporting individuals who have experienced trauma, such as physical abuse or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [19]. This evidence-based intervention integrates cognitive and behavioral techniques to address and modify maladaptive thought patterns, alleviate trauma-related symptoms—including guilt, shame, and anxiety—and enhance emotional regulation skills [20]. TF-CBT assists survivors in reframing unhelpful beliefs about themselves and others, reducing avoidant behaviors, and building resilience to manage distressing emotions effectively [21]. Research consistently demonstrates its effectiveness in reducing symptoms of PTSD and depression, while also improving self-efficacy and enhancing overall quality of life, particularly among women survivors [22, 23].

Given the high prevalence of domestic violence against women and its profound psychological repercussions, including chronic guilt, dysregulated emotions, and insecure attachment patterns, this research holds significant importance. Many victims face substantial barriers, such as cultural stigma and limited access to specialized services, while existing interventions often fail to adequately address the specific psychological needs of this vulnerable group. By focusing on the effectiveness of TF-CBT as a targeted approach, this study seeks to fill a critical gap in the Iranian research literature, providing scientific evidence for culturally adapted treatment protocols and supportive policies within welfare and social emergency centers. Furthermore, simultaneously examining the impact on guilt, emotion regulation, and attachment style offers a more comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms of recovery in this population, representing a notable innovation in trauma psychology. Therefore, the present study aims to answer the question: Is TF-CBT effective in reducing guilt, improving emotion regulation, and modifying attachment styles in women victims of domestic violence at the Ahvaz Welfare Center?

Materials and Methods

This study employed a quasi-experimental design, specifically a pre-test/post-test approach with a control group, to investigate the effectiveness of TF-CBT. The statistical population for this research included all women victims of domestic violence who sought assistance at the Ahvaz Welfare Center in 2024, totaling approximately 150 referrals based on center records. From this population, a convenience sample of 33 participants was carefully selected. The sample size was determined based on guidelines by Cohen [24], which recommend a minimum of 15 to 20 participants per group for sufficient statistical power in quasi-experimental designs, assuming a medium to large effect size. The slight difference in group sizes (16 in the experimental group and 17 in the control group) resulted from random assignment and one participant’s withdrawal from the experimental group due to relocation, with no further attrition observed. Participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (n=16) or the control group (n=17).

Inclusion criteria for participants included women victims of domestic violence presenting to the Ahvaz Welfare Center, aged between 20 and 50 years, demonstrating trauma-related symptoms as per DSM-5 criteria, achieving a score above the mean on the domestic violence questionnaire, possessing at least basic literacy, and expressing willingness to participate in the study without receiving concurrent psychotherapy. Exclusion criteria comprised severe psychiatric disorders (e.g. psychosis, active substance abuse), active suicidal ideation, attendance below 80% of the intervention sessions, and experiencing severe stressful life events during the study period. To encourage participant cooperation and attendance in the context of Ahvaz’s cultural setting, where stigma around mental health and domestic violence is prevalent, strategies such as building trust through initial rapport-building sessions, offering flexible scheduling, and providing culturally sensitive psychoeducation were employed, as recommended by Kazemi Khooban et al. [23]. To control for confounding variables, the study standardized session delivery, ensured facilitator training, and monitored external stressors through regular check-ins, though complete control of variables like prior trauma history was not feasible. Ethical considerations were paramount throughout the research process. All participants provided informed consent, and their confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained. After baseline pre-test assessments for both groups, the experimental group received the intervention, while the control group did not, followed by post-test assessments. Following the conclusion of the study, the control group was offered the intervention in a condensed format.

Measure

Guilt inventory: The guilt inventory, developed by Jones et al. [25], is a 45-item self-report measure designed to assess various aspects of guilt comprehensively. Participants rate their agreement with each statement on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). The scoring ranges for the scales are from 45 to 225. Higher scores on the guilt subscales indicate a greater presence of guilt. Shahmiri et al. [26] reported a Cronbach’s α of 0.74 for the instrument, indicating acceptable internal consistency. For the present study, the Cronbach’s α for the Guilt Inventory was calculated to be 0.82, demonstrating acceptable reliability.

Emotion regulation questionnaire (ERQ): The ERQ, developed by Hofmann and Kashdan [27], is a 20-item self-report measure designed to assess an individual’s habitual use of various emotion regulation strategies. Participants respond using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“not at all true for me”) to 5 (“completely true for me”), with total scores ranging from 20 to 100. Higher scores indicate better emotion regulation abilities. A Persian validation study by Soleimani et al. [28] reported a Cronbach’s α of 0.81, demonstrating good internal consistency. In the present study, the overall Cronbach’s α coefficient for the ERQ was 0.86, further confirming its reliability and validity for use with an Iranian sample.

Experiences in close relationships-revised (ECR-R): The ECR-R, developed by Fraley et al. [29], serves as a robust and widely utilized 36-item self-report measure for assessing adult attachment styles. This scale effectively differentiates between two continuous dimensions of insecure attachment: Anxiety and avoidance. The anxiety subscale, consisting of 18 items, evaluates the degree to which individuals worry about abandonment, rejection, or insufficient responsiveness from close others (e.g. “I often worry that my partner doesn’t really love me”). The avoidance subscale, also with 18 items, measures the extent to which individuals feel uncomfortable with closeness and intimacy, preferring self-reliance and emotional distance (e.g. “I feel uncomfortable when others get too close to me”). Participants rate each statement on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”). The score range for both the anxiety and avoidance subscales is from 18 to 126. Higher scores on either subscale indicate a greater degree of that specific insecure attachment pattern. In the Iranian standardization study conducted by Pooravari and Fathi Ashtiani [30], the Cronbach’s α coefficient was reported as 0.81, indicating good internal consistency. In the present study, the ECR-R demonstrated strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.87.

Intervention

TF-CBT: The TF-CBT intervention, designed based on the structured protocol outlined by Cohen et al. [31], was administered to the experimental group over eight weekly 90-minute sessions. This structured therapy aims to address the multi-faceted impacts of trauma, including guilt, emotion dysregulation, and insecure attachment styles. The sessions systematically guided participants through various therapeutic components, building skills for emotional processing and cognitive restructuring. A summary of the sessions is provided in Table 1, outlining the topic, session title, and homework assignments for each week.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) in SPSS software, version 27. Descriptive statistics, including Mean±SD, and frequency distributions, were calculated for all variables. Prior to conducting the ANCOVA, key statistical assumptions were thoroughly evaluated. Data normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, homogeneity of variances was examined with Levene’s test, homogeneity of regression slopes was verified using an interaction term test between the covariate and the independent variable, and the assumption of linearity between pre-test and post-test scores was checked using scatterplots and Pearson correlation coefficients.

Results

The demographic analysis of the participants revealed that 53% of the subjects were in the age range of 20 to 32 years, while the remaining 47% fell into the 33 to 45-year age bracket. The mean age for the experimental group was 28.29±4.12 years, and for the control group, it was 33.18±5.37 years. This distribution indicates a relatively young adult sample, which is representative of women who may be experiencing domestic violence and seeking support at welfare centers. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics, including Mean±SD, for the research variables (guilt, emotion regulation, and attachment styles) for both the experimental and control groups at pre-test and post-test. Additionally, the table includes the results of within-group (paired t-tests) and between-group (independent t-tests) comparisons for each construct.

Prior to conducting inferential analyses, the assumption of normality for the data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, with results indicating that the data for all research variables were normally distributed within both the experimental and control groups (all P>0.05). Additional ANCOVA assumptions were evaluated: Homogeneity of variances was confirmed using Levene’s test (all P>0.05), equality of covariance matrices across groups was verified using Box’s M test (P=0.127), and the assumption of sphericity was not applicable as each dependent variable was analyzed separately in univariate ANCOVA models. To determine the effectiveness of TF-CBT on the dependent variables (guilt, emotion regulation, anxious attachment style, and avoidant attachment style) after controlling for pre-test scores, an ANCOVA was performed. Before the ANCOVA, the assumptions of homogeneity of variances, assessed by Levene’s test, and homogeneity of regression slopes were confirmed (all P>0.05). Table 3 presents the results of the ANCOVA, including effect sizes (partial η²).

As shown in Table 3, the results of the ANCOVA revealed a statistically significant effect of TF-CBT on all dependent variables, after controlling for pre-test scores. Specifically, for guilt, there was a significant reduction in post-test scores in the experimental group compared to the control group (F=443.33, P<0.001, η²=0.94). This large effect size suggests a substantial reduction in guilt, with clinical significance indicated by a mean decrease of 40.25 points in the experimental group, surpassing the threshold for meaningful change. Similarly, TF-CBT significantly improved emotion regulation (F=130.14, P<0.001, η²=0.83), indicating a large effect and clinically meaningful improvement, as the experimental group’s mean score increased by 35 points, reflecting enhanced adaptive emotion regulation strategies. Furthermore, the therapy significantly reduced anxious attachment style (F=633.98, P<0.001, η²=0.96) and avoidant attachment style (F=239.39, P<0.001, η²=0.90). These large effect sizes suggest clinically significant shifts toward secure attachment, as post-test scores for both anxious and avoidant subscales in the experimental group fell below the threshold for insecure attachment.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of TF-CBT in addressing key psychological sequelae in women survivors of domestic violence, specifically focusing on guilt, emotion regulation, and insecure attachment styles. The significant findings revealed that TF-CBT profoundly impacted all targeted variables, leading to a substantial reduction in guilt, a marked improvement in emotion regulation abilities, and a significant modification of both anxious and avoidant attachment styles. These results underscore the multidimensional efficacy of TF-CBT as a critical intervention for this vulnerable population.

The observed significant reduction in feelings of guilt among women survivors of domestic violence following TF-CBT aligns robustly with existing literature. This finding resonates with the work of Young et al. [32], who similarly reported that cognitive behavioral approaches are highly effective in alleviating trauma-related guilt. The efficacy can be attributed to TF-CBT’s core principles of cognitive restructuring, which directly challenges distorted cognitions and maladaptive beliefs frequently held by victims, such as self-blame or a sense of responsibility for the abuse endured [21]. By systematically identifying and correcting these ingrained thought patterns, TF-CBT facilitates a healthier reinterpretation of the traumatic events, thereby diminishing the pathological sense of guilt and fostering a more accurate self-perception. Furthermore, the behavioral components of TF-CBT, including gradual exposure to trauma-related memories, enable emotional processing that can alleviate the emotional burden often associated with chronic guilt [32]. This process helps survivors break the cycle of avoidance and integrate the traumatic experience in a less self-condemnatory manner.

Consistent with our findings, TF-CBT demonstrably enhanced emotion regulation capacities in women affected by domestic violence, a result that is in harmony with previous research by Dumornay et al. [33] and Ford et al. [34]. This improvement can be primarily attributed to TF-CBT’s emphasis on teaching adaptive emotional skills. Survivors of repeated trauma often develop maladaptive emotional responses, oscillating between emotional suppression and explosive outbursts [20]. The therapy addresses these dysregulated patterns by providing explicit training in emotion identification, distress tolerance, and cognitive reappraisal, which are vital for managing intense emotional reactions effectively [33]. By correcting distorted cognitive-emotional cycles, where distorted interpretations of events lead to disproportionate emotional responses, TF-CBT equips individuals with robust strategies to modulate their emotions adaptively [18]. Techniques such as controlled exposure to distressing stimuli gradually reduce emotional hypersensitivity, thereby increasing their capacity to manage tension and stress without resorting to maladaptive coping mechanisms [22].

Moreover, the study revealed that TF-CBT significantly modified insecure attachment styles, encompassing both anxious and avoidant dimensions, in women survivors of domestic violence. This outcome is consistent with the findings of Allen and Brown [35], who noted similar positive shifts in attachment patterns through attachment-focused interventions. TF-CBT’s efficacy in this domain stems from its ability to impact deeply ingrained relational schemas that often underpin insecure attachment. For individuals with anxious attachment, the therapy challenges core beliefs like “I cannot survive without a relationship” or “I am to blame for abuse”, fostering a shift toward greater self-reliance and reduced fear of abandonment [16]. Through simulated relational scenarios and assertiveness training, survivors learn to articulate their needs without fearing relational rupture. For those with avoidant attachment, characterized by emotional distancing and distrust, TF-CBT works to reconstruct interpersonal trust and dismantle beliefs such as “trusting others leads to harm”. By facilitating corrective emotional experiences within a safe therapeutic environment and promoting gradual engagement in healthy relationships, the therapy helps survivors build flexible boundaries and develop the capacity for secure attachment without fear of re-traumatization [35].

The comprehensive positive impact of TF-CBT on guilt, emotion regulation, and attachment styles highlights its potential as a holistic intervention for women survivors of domestic violence. These findings contribute significantly to the existing body of knowledge, particularly within the Iranian context, by providing empirical support for targeted, culturally sensitive therapeutic protocols. Integrating TF-CBT into welfare and social emergency centers can offer a pathway towards enhanced psychological well-being, fostering resilience, and promoting the development of healthier interpersonal relationships for this vulnerable population.

Conclusion

Based on the compelling findings of this study, TF-CBT is unequivocally demonstrated as a highly effective intervention for women victims of domestic violence. The significant reductions in guilt, substantial improvements in emotion regulation, and profound modifications of insecure attachment styles highlight TF-CBT’s comprehensive capacity to ameliorate the complex psychological sequelae of intimate partner violence. These results underscore the critical importance of integrating TF-CBT into therapeutic protocols and support services, offering a robust pathway towards fostering resilience, promoting psychological well-being, and enabling healthier relational functioning for this vulnerable population.

Despite its promising results, this study faced certain limitations, including a relatively limited sample size, the inability to control for all potential intervening variables such as the duration and severity of experienced violence, and the lack of a long-term follow-up to assess the sustained effects of the intervention.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was granted ethical approval by the Ethics Committee of the Islamic Azad University, Ahvaz Branch, Iran (Code: IR.IAU.AHVAZ.REC.1404.077).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Ahvaz Welfare Center for their cooperation and support, and to all the women who participated in this study for their valuable time and trust.

References

- Wessells MG, Kostelny K. The psychosocial impacts of intimate partner violence against women in LMIC contexts: Toward a holistic approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19(21):14488. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph192114488] [PMID]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Violence against women. 2021 [Updated 2024 March 25]. Available from: [Link]

- Lanchimba C, Díaz-Sánchez JP, Velasco F. Exploring factors influencing domestic violence: A comprehensive study on intrafamily dynamics. Front Psychiatry. 2023; 14:1243558. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1243558] [PMID]

- Hajnasiri H, Ghanei Gheshlagh R, Sayehmiri K, Moafi F, Farajzadeh M. Domestic violence among Iranian women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016; 18(6):e34971. [DOI:10.5812/ircmj.34971] [PMID]

- Brockstedt M, Uğur Baysal S, Daştan K. The impact of domestic violence and sexual assault on family dynamics and child development: A comprehensive review. Turk Arch Pediatr. 2025; 60(1):5-12. [DOI:10.5152/TurkArchPediatr.2025.24169] [PMID]

- Howell KH, Barnes SE, Miller LE, Graham-Bermann SA. Developmental variations in the impact of intimate partner violence exposure during childhood. J Inj Violence Res. 2016;8(1):43-57. [DOI:10.5249/jivr.v8i1.663] [PMID]

- Kurbatfinski S, Letourneau N, Novick J, Marshall S, Griggs K, McBride D, et al "Don't you love me?" Abusers' use of shame-to-guilt to coercively control 2SLGBTQQIA+ individuals and rural women experiencing intimate partner violence. Womens Health. 2025; 21:17455057251335361. [DOI:10.1177/17455057251335361] [PMID]

- Siegel A, Shaked E, Lahav Y. A complex relationship: intimate partner violence, identification with the aggressor, and guilt. Violence Against Women. 2024; 30(2):445-59. [DOI:10.1177/10778012221137917] [PMID]

- Beck JG, McNiff J, Clapp JD, Olsen SA, Avery ML, Hagewood JH. Exploring negative emotion in women experiencing intimate partner violence: Shame, guilt, and PTSD. Behav Ther. 2011; 42(4):740-50. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2011.04.001] [PMID]

- Muñoz-Rivas M, Bellot A, Montorio I, Ronzón-Tirado R, Redondo N. Profiles of emotion regulation and post-traumatic stress severity among female victims of intimate partner violence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18(13):6865. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18136865] [PMID]

- Behroz M, Marashian FS, Alizadeh M. The relationship of social support and psychological capital with empowerment of female heads of households: The mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation. Caspian J Health Res. 2023; 8(2):93. [DOI:10.32598/CJHR.8.2.408.2]

- Bliton CF, Wolford-Clevenger C, Zapor H, Elmquist J, Brem MJ, Shorey RC, et al. Emotion dysregulation, gender, and intimate partner violence perpetration: An exploratory study in college students. J Fam Violence. 2016; 31(3):371-7. [DOI:10.1007/s10896-015-9772-0] [PMID]

- Baniaghil A, Hamdi H, Aghili S M, Vakili M. The association between emotion regulation and domestic violence in couples. J Nurs Midwifery Sci. 2025; 12(2):e148025. [DOI:10.5812/jnms-148025]

- SadeghMohammadi F, Spencer CM. The relationship between intimate partner violence and parenting styles with mediated attachment styles in Iranian women. Discov Glob Soc. 2024; 2(1):75. [DOI:10.1007/s44282-024-00106-z]

- Moradi Janati A, Salehi S, Shaygan Majd F. The mediating role of emotional regulation in the relationship between attachment styles and psychological well-being. Caspian J Health Res. 2024; 9(2):85. [DOI:10.32598/CJHR.9.2.463.2]

- Kural AI, Kovacs M. The role of anxious attachment in the continuation of abusive relationships: The potential for strengthening a secure attachment schema as a tool of empowerment. Acta Psychol. 2022; 225:103537. [DOI:10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103537] [PMID]

- Almeida I, Nobre C, Marques J, Oliveira P. Violence against Women: Attachment, psychopathology, and beliefs in intimate partner violence. Soc Sci. 2023; 12(6):346. [DOI:10.3390/socsci12060346]

- de Arellano MA, Lyman DR, Jobe-Shields L, George P, Dougherty RH, Daniels AS, et al. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for children and adolescents: Assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014; 65(5):591-602. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ps.201300255] [PMID]

- Ennis N, Sijercic I, Monson CM. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder under ongoing threat: A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021; 88:102049. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102049] [PMID]

- Chipalo E. Is trauma focused-cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) effective in reducing trauma symptoms among traumatized refugee children? A systematic review. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2021; 14(4):545-58. [DOI:10.1007/s40653-021-00370-0] [PMID]

- Brown EJ, Cohen JA, Mannarino AP. Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy: The role of caregivers. J Affect Disord. 2020; 277:39-45. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.123] [PMID]

- Zemestani M, Mohammed AF, Ismail AA, Vujanovic AA. A pilot randomized clinical trial of a novel, culturally adapted, trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral intervention for war-related PTSD in Iraqi women. Behav Ther. 2022; 53(4):656-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2022.01.009] [PMID]

- Kazemi Khooban SZ, Poursharifi H, Kakavand AR, Geyanbagheri M. The effectiveness of the revised protocol of trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy (TF-CBT) on the quality of life and psychological distress in female victims of domestic violence. Shenakht. 2022; 9(2):62-75. [DOI:10.32598/shenakht.9.2.62]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 1988. [DOI:10.4324/9780203771587]

- Jones WH, Schratter AK, Kugler K. The guilt inventory. Psychol Rep. 2000; 87(3 Pt 2):1039-42. [DOI:10.2466/pr0.2000.87.3f.1039] [PMID]

- Shahmiri N, Azizi LS, Abolghasemzadeh M, Sangany A. The role of mediating self-compassion in the relationship between the symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder with nurses’ guilty feelings. Career Organ Couns. 2020; 12(43):133-50. [DOI:10.52547/jcoc.12.2.133]

- Hofmann SG, Kashdan TB. The affective style questionnaire: Development and psychometric properties. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2010; 32(2):255263. [DOI:10.1007/s10862-009-9142-4] [PMID]

- Soleimani S, Mofrad F, Kareshki H. Interpersonal emotion regulation questionnaire (IERQ) in Persian speaking population: Adaption, Factor Structure and Psychometric Properties. Int J Appl Behav Sci. 2018; 3(4):42-9. [DOI:10.22037/ijabs.v3i4.16483]

- Fraley RC, Waller NG, Brennan KA. Experiences in close relationships questionnaire-revised. Washington: APA PsycTests; 2000. [DOI:10.1037/t03763-000]

- Pooravari M, Fathi Ashtiani A. Reliability, validity, and factor structure of experiences in close relationships scale–revised for using in children and adolescents (ECR-RC). Int J Behavi Sci. 2017; 11(1):5-10. [Link]

- Cohen JA, Mannarino AP, Deblinger E. Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. [Link]

- Young K, Chessell ZJ, Chisholm A, Brady F, Akbar S, Vann M, et al. A cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) approach for working with strong feelings of guilt after traumatic events. Cogn Behav Ther. 2021; 14:e26. [DOI:10.1017/S1754470X21000192]

- Dumornay NM, Finegold KE, Chablani A, Elkins L, Krouch S, Baldwin M, et al. Improved emotion regulation following a trauma-informed CBT-based intervention associates with reduced risk for recidivism in justice-involved emerging adults. Front Psychiatry. 2022; 13:951429. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.951429] [PMID]

- Ford JD, Grasso DJ, Levine J, Tennen H. Emotion regulation enhancement of cognitive behavior therapy for college student problem drinkers: A pilot randomized controlled trial. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2018; 27(1):47-58. [DOI:10.1080/1067828X.2017.1400484] [PMID]

- Allen B, Brown MP. Attachment security as an outcome and predictor of response to trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy among maltreated children with posttraumatic stress: A pilot study. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2023; 28(3):1080-91. [DOI:10.1177/13591045221144588] [PMID]

Article Type: Original Contributions |

Subject:

Health Education and Promotion

Received: 2025/07/19 | Accepted: 2025/08/30 | Published: 2025/10/1

Received: 2025/07/19 | Accepted: 2025/08/30 | Published: 2025/10/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |