Volume 10, Issue 4 (10-2025)

CJHR 2025, 10(4): 265-274 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.GUMS.REC.1404.086

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Jedinia A, Joukar F, Maroufizadeh S, Asgharnezhad M, Pourseyedian A, Mansour-Ghanaei F et al . Link Between Helicobacter pylori Infection and Colorectal Polyps: Implications for Screening in Northern Iran. CJHR 2025; 10 (4) :265-274

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-439-en.html

URL: http://cjhr.gums.ac.ir/article-1-439-en.html

Alieh Jedinia1

, Farahnaz Joukar2

, Farahnaz Joukar2

, Saman Maroufizadeh3

, Saman Maroufizadeh3

, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad2

, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad2

, Abed Pourseyedian4

, Abed Pourseyedian4

, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei1

, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei1

, Kourosh Mojtahedi *5

, Kourosh Mojtahedi *5

, Farahnaz Joukar2

, Farahnaz Joukar2

, Saman Maroufizadeh3

, Saman Maroufizadeh3

, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad2

, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad2

, Abed Pourseyedian4

, Abed Pourseyedian4

, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei1

, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei1

, Kourosh Mojtahedi *5

, Kourosh Mojtahedi *5

1- Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Razi Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. & Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

2- Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- Department of Biostatistics, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

4- Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Razi Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

5- Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Razi Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. & Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,K.moj2013@gmail.com

2- Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

3- Department of Biostatistics, School of Health, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

4- Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Razi Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

5- Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Razi Hospital, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. & Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases Research Center, Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 670 kb]

(116 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (489 Views)

Full-Text: (76 Views)

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains a major public health concern worldwide, ranking as the third most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality [1]. Colorectal polyps, particularly adenomatous and serrated types, are well-established precursor lesions that play a critical role in the adenoma carcinoma sequence [2, 3]. Identifying and understanding the modifiable risk factors contributing to colorectal polyp formation is vital for the development of effective preventive strategies against CRC [4]. Recent research has increasingly focused on the role of gastrointestinal microbiota and chronic infections in the pathogenesis of colorectal neoplasia. Among these, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), a Gram-negative, microaerophilic bacterium that colonizes the human stomach and is implicated in chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, and gastric cancer has drawn attention for its potential association with extragastric malignancies, including CRC [5–7].

Mechanistically, H. pylori may influence colorectal carcinogenesis via systemic inflammatory responses, alterations in gastric acid secretion, changes in gut microbiota, or through the release of carcinogenic metabolites such as ammonia and N-nitroso compounds [8–10]. Epidemiological studies examining the link between H. pylori infection and colorectal polyps have yielded mixed results. Several meta-analyses and case-control studies have reported a significant association between H. pylori seropositivity and increased risk of colorectal polyps and adenomas [11, 12], whereas others have found no clear relationship [13, 14]. These inconsistencies may be attributed to variations in geographic regions, diagnostic methods, H. pylori strains, host genetic factors, and environmental exposures. Notably, studies suggest that the effect of H. pylori may be more pronounced in populations with high background infection rates and differing gut microbial profiles [6, 15, 16].

Iran, particularly its northern regions along the Caspian Sea, exhibits a relatively high prevalence of both H. pylori infection and CRC incidence compared to global averages [16, 17]. Despite this epidemiological overlap, limited population-based studies have explored the potential association between H. pylori infection and colorectal polyps in this region. Given the unique demographic, dietary, and microbial characteristics of northern Iran, investigating this relationship is both timely and regionally relevant. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the association between H. pylori infection and the presence of colorectal polyps in individuals undergoing colonoscopy in northern Iran. By identifying potential infectious contributors to colorectal polyp formation, this research may enhance our understanding of CRC risk stratification and inform tailored screening and prevention strategies in high-risk populations.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted at Razi Hospital, the main gastroenterology referral center in Rasht, northern Iran between May 2024 and July 2024. All eligible individuals referred for both upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy were recruited using a census and convenience sampling strategy. All procedures complied with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Study population and eligibility criteria

Adults aged 18 years and older who were referred for diagnostic upper endoscopy and colonoscopy were considered eligible for inclusion in the study. Based on an expected prevalence of colorectal polyps of 34.6% [18], a 95% confidence level, and 80% power to detect an odds ratio of 1.8 for the association with H. pylori, the minimum required sample size was calculated as 370 participants. Individuals were excluded if they were unable to complete adequate bowel preparation, had a history of gastrointestinal malignancy or were under ongoing follow-up for known gastrointestinal cancers, had prior gastrointestinal surgery other than polypectomy, presented with active gastrointestinal bleeding at the time of evaluation, had used proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) without discontinuation for at least two weeks prior to endoscopy to avoid false-negative H. pylori results [19], had received antibiotics within the preceding month, or had previously undergone eradication therapy for H. pylori infection.

Data collection and instruments

Data were collected using a standardized case-report form and structured questionnaire, administered by a trained research team. The questionnaire gathered demographic (age, sex, education level, marital status, occupation), lifestyle (smoking status, alcohol consumption), clinical (underlying diseases, family history of CRC). and body mass index (BMI). Anthropometric measurements were performed by trained staff using a calibrated digital scale (Seca 803, Germany) for weight and a stadiometer for height.

Assessment of H. pylori infection

All participants underwent upper endoscopy using a standard video gastroscope (FUJIFILM, Japan). During the procedure, multiple biopsies were obtained, usually two from the gastric body and two from the antrum, for histopathological examination. The presence of H. pylori was confirmed by pathologist reports using Giemsa staining for improved detection sensitivity.

Colonoscopy procedure and polyp evaluation

Colonoscopy was performed on all subjects by gastroenterologists blinded to participants’ H. pylori status using standard colonoscopy systems (FUJIFILM, Japan). Bowel preparation involved a clear liquid diet for 24 hours, with a regimen including Bisacodyl tablets, Sena-Graph syrup, and Pidrolax powder, in accordance with local institutional protocol. Solid foods and colored liquids were avoided; antidiabetic and cardiovascular medications were managed under specialist guidance. When polyps were detected, polypectomy was performed using cold snare forceps for polyps ≤1 cm and hot snare forceps for polyps >1 cm, in accordance with established endoscopic guidelines [20, 21]. Excised specimens were placed in 10% formalin and transferred to the pathology department, which was blinded to H. pylori status.

Polyp size was determined by visual comparison with biopsy forceps and confirmed by direct measurement of the specimen with a surgical ruler. Histopathological classification was based on World Health Organization (WHO) criteria and included [22]: Tubular adenoma, tubulovillous adenoma, serrated adenoma, hyperplastic polyp, inflammatory polyp, and sessile serrated lesions . Polyps were further categorized by size: <0.5 cm, 0.5–1 cm, and >1 cm. Participants were categorized into four groups based on their H. pylori infection status and the presence or absence of colorectal polyps: Those with both H. pylori infection and polyps, those with H. pylori infection but no polyps, those without H. pylori infection who had polyps, and those without H. pylori infection and no polyps.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were reported as Mean±SD. Differences in the prevalence of colorectal polyps across sex and age groups were assessed using the chi-square test and the cochran-armitage test for trend. The prevalence of colorectal polyps among participants with and without H. pylori infection was also compared using the chi-square test. To evaluate the association between H. pylori infection and the presence of colorectal polyps, logistic regression analysis was performed in both crude and adjusted models. Results were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and a two-tailed P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism software, version 8.0.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Participant demographics and clinical characteristics

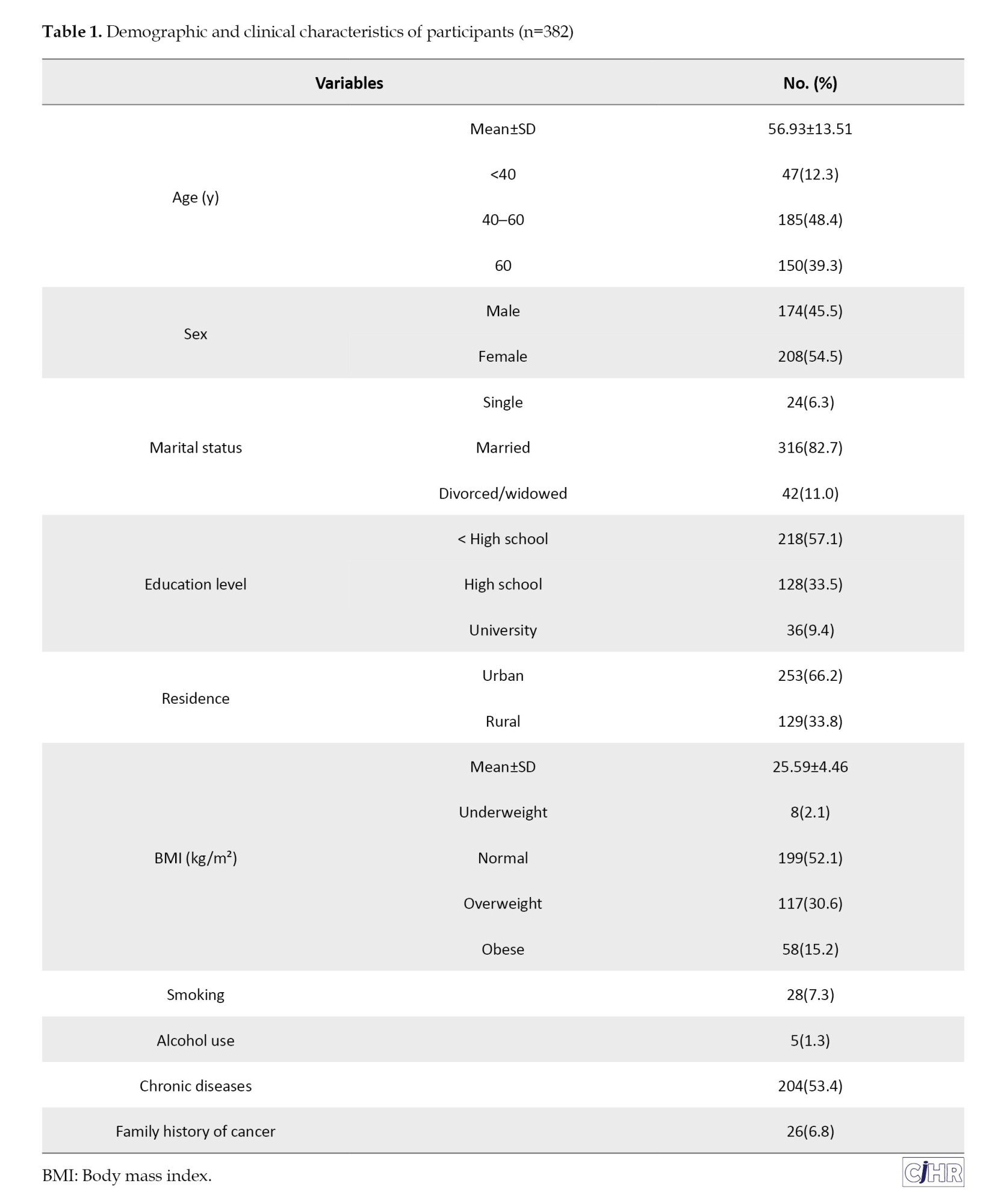

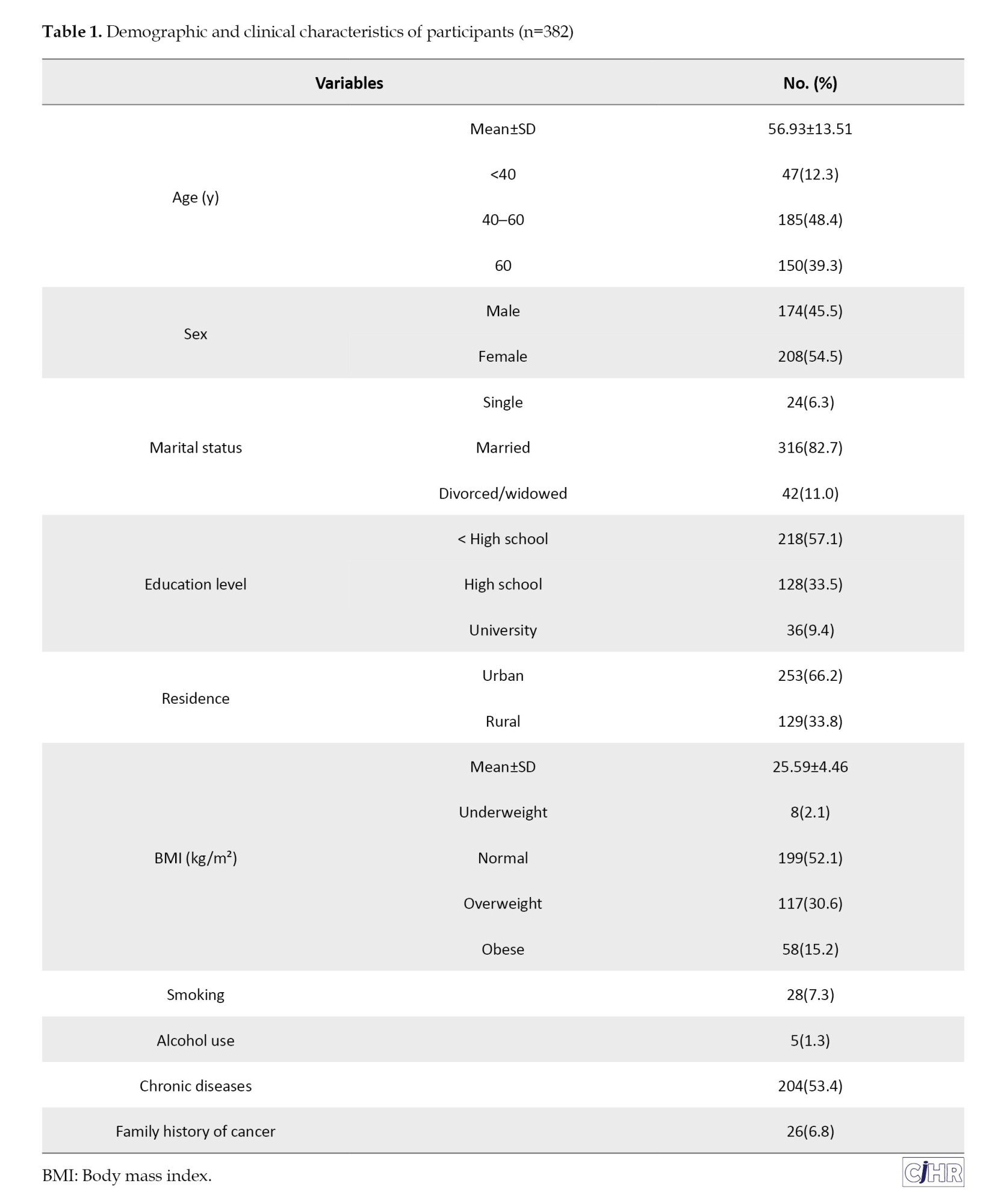

A total of 382 individuals referred to the endoscopy unit at Razi Hospital in Rasht were included in the study. The mean age of participants was 56.93±13.51 years, with 39.3% (n=150) aged above 60 years. Women accounted for 54.5% (n=208) of the study population. The majority were married (82.7%, n=316), and 66.2% (n=253) resided in urban areas. Only 9.4% (n=36) had a university education, while 57.1% (n=218) had not completed high school. The mean BMI was 25.59±4.46 kg/m², and 15.2% (n=58) of participants were categorized as obese. Smoking and alcohol use were reported in 7.3% (n=28) and 1.3% (n=5), respectively. A total of 53.4% (n=204) had at least one underlying medical condition, and 6.8% (n=26) reported a family history of cancer (Table 1).

Prevalence of H. pylori infection and colorectal polyps

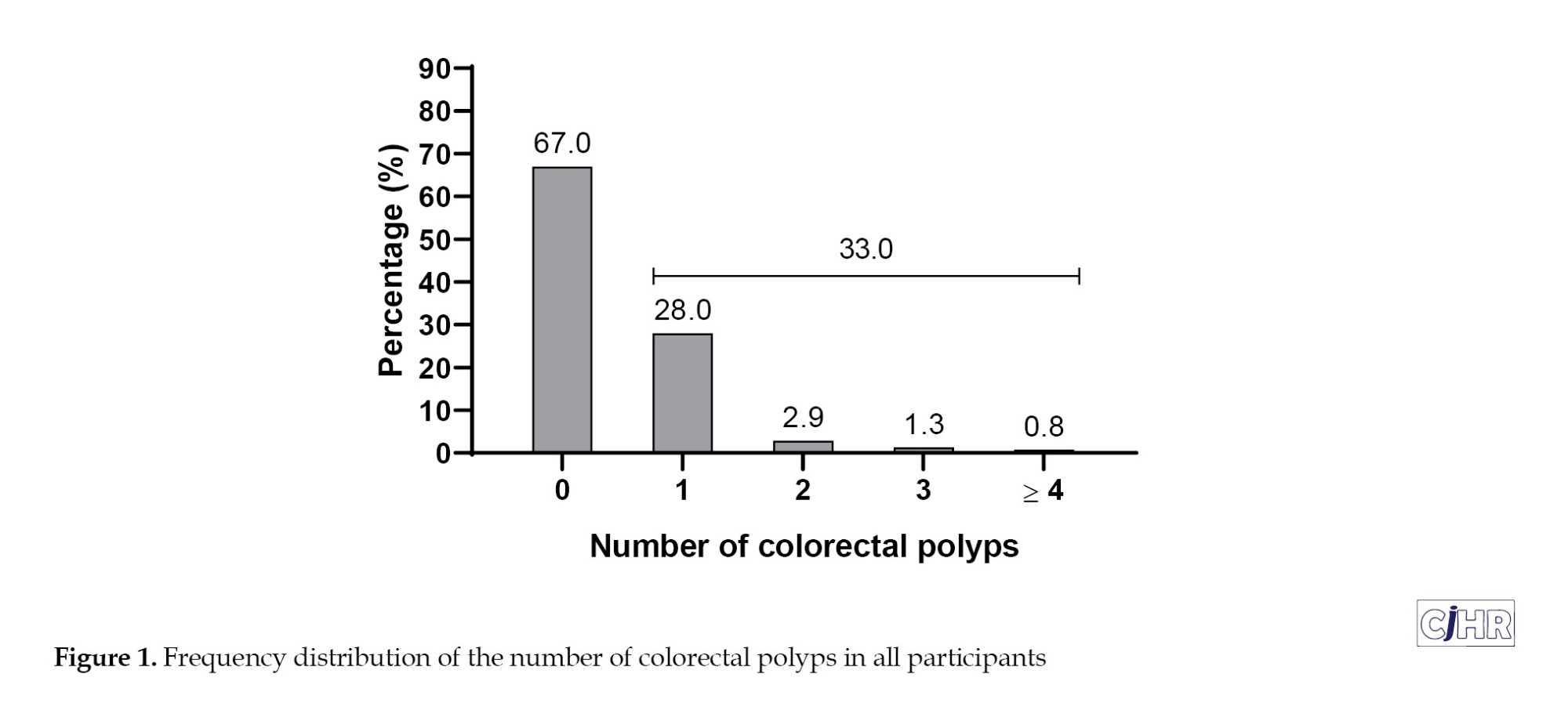

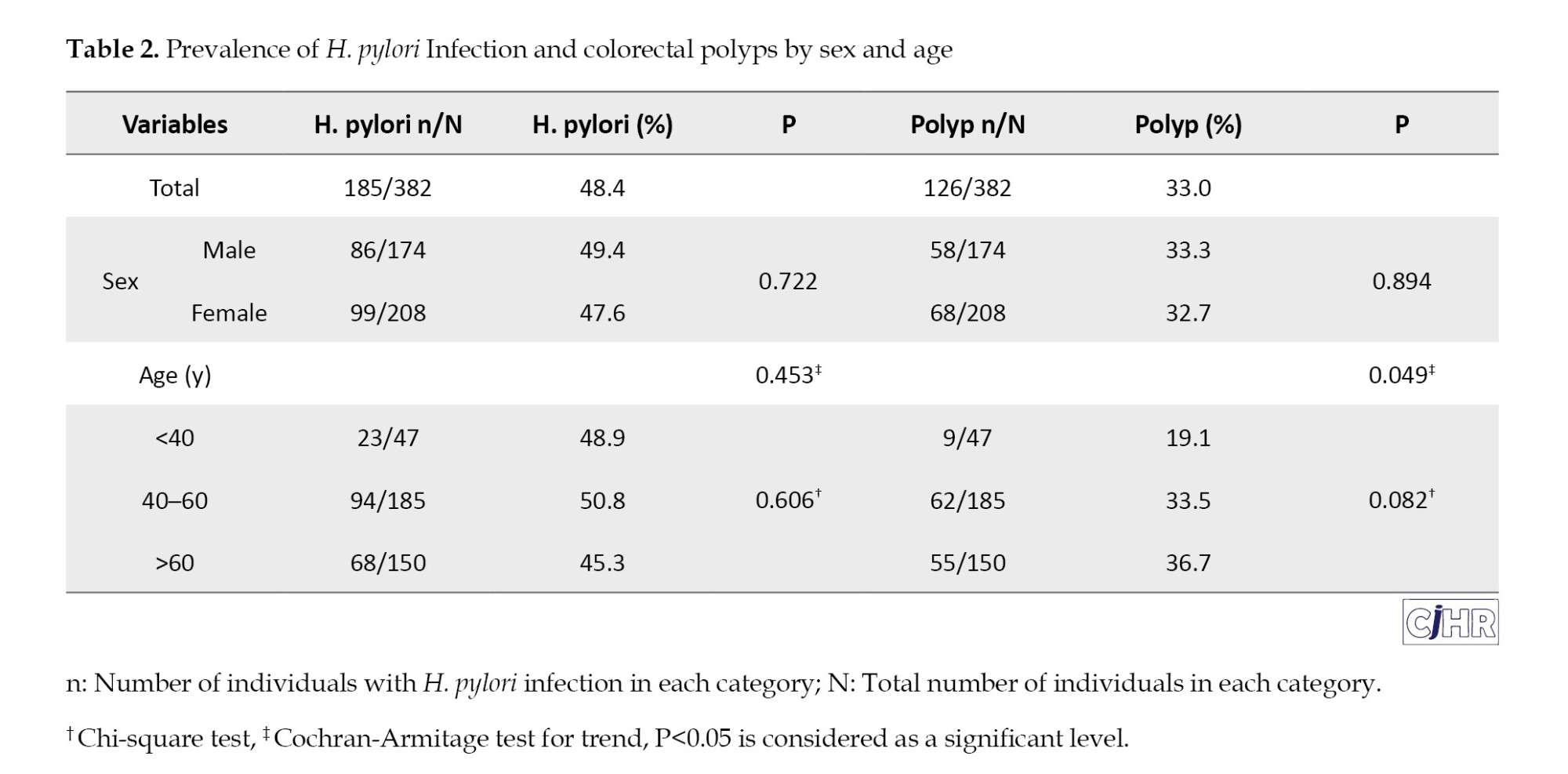

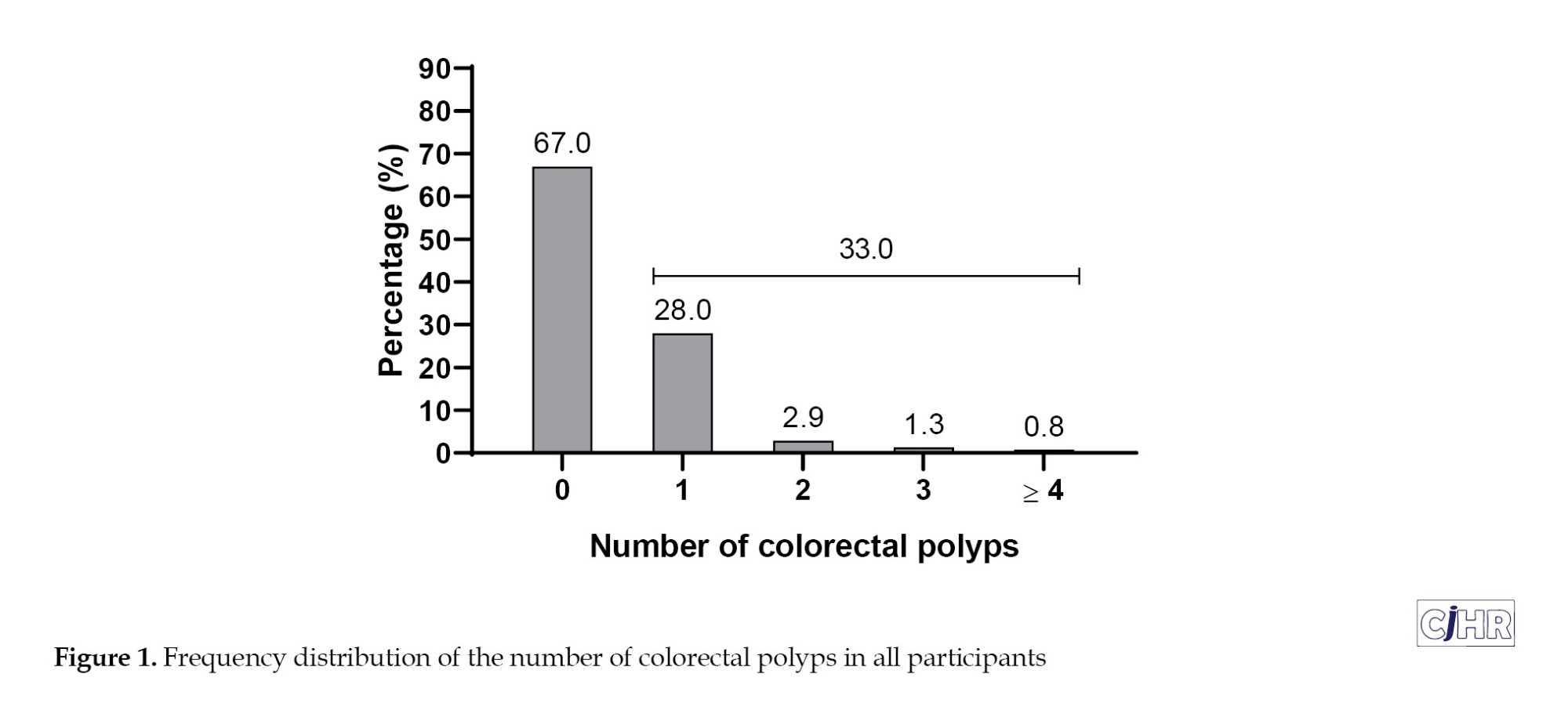

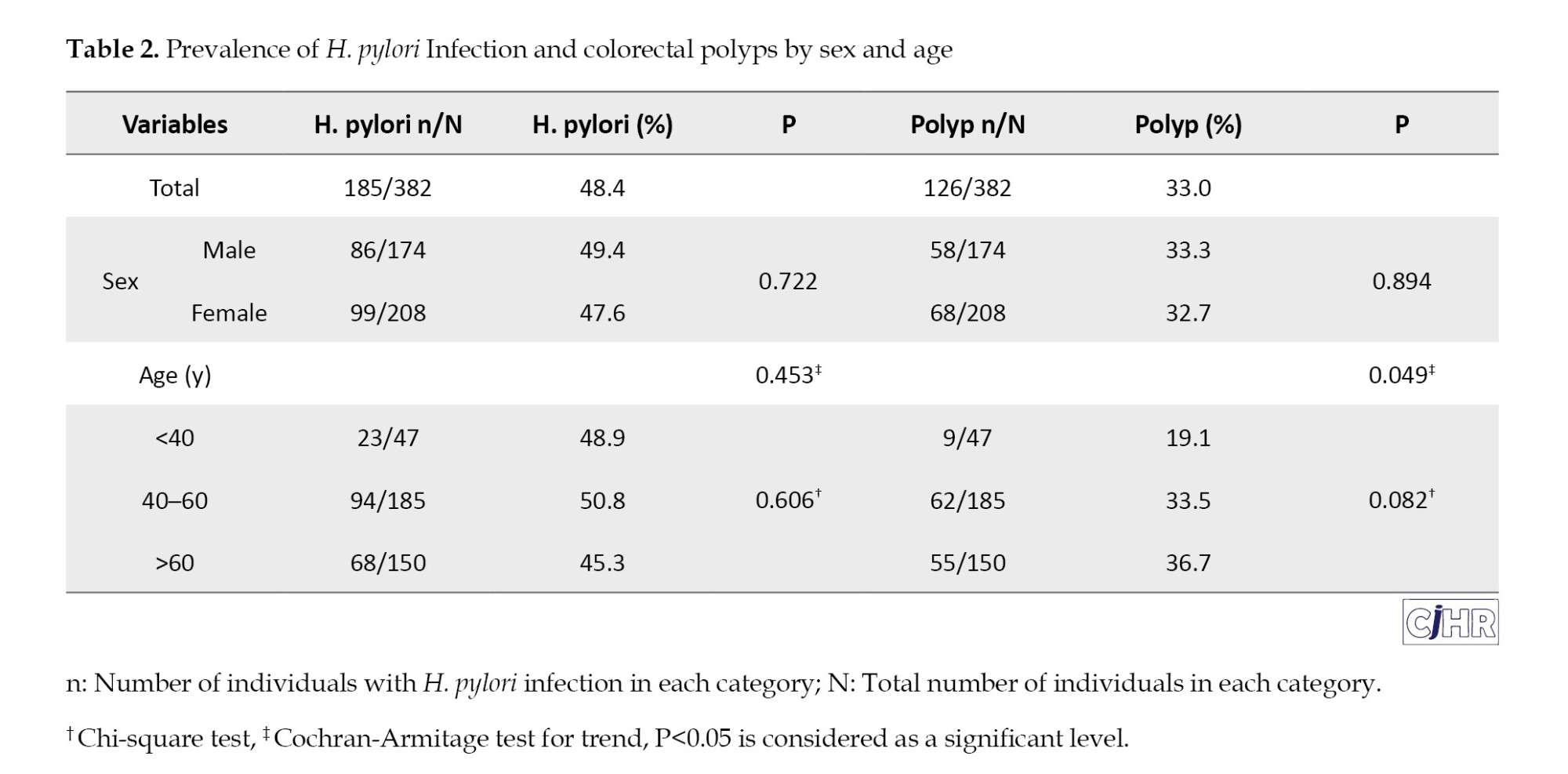

The overall prevalence of H. pylori infection was 48.4% (n=185). The prevalence did not differ significantly between men and women (49.4% vs 47.6%, P=0.722) or among age groups (48.9% in <40 years, 50.8% in 40–60 years, 45.3% in >60 years; P for trend = 0.453) (Table 2). The overall prevalence of colorectal polyps was 33.0% (n=126) (Table 2, Figure 1).

No significant sex difference was observed (33.3% in men vs. 32.7% in women; P=0.894). However, polyp prevalence increased significantly with age: 19.1% in participants <40 years, 33.5% in those 40–60 years, and 36.7% in those >60 years (P for trend=0.049) (Table 2).

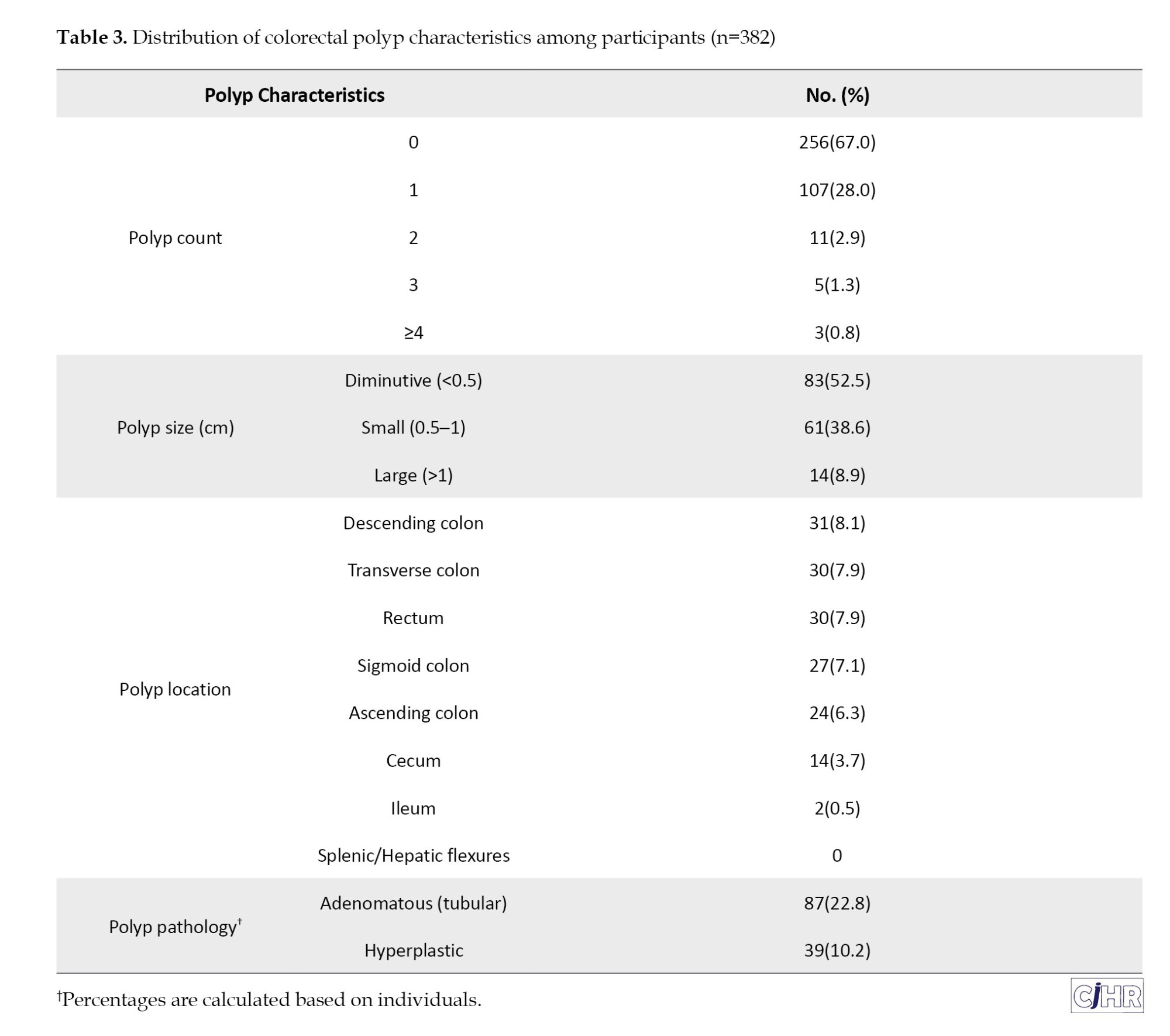

Colorectal polyp characteristics

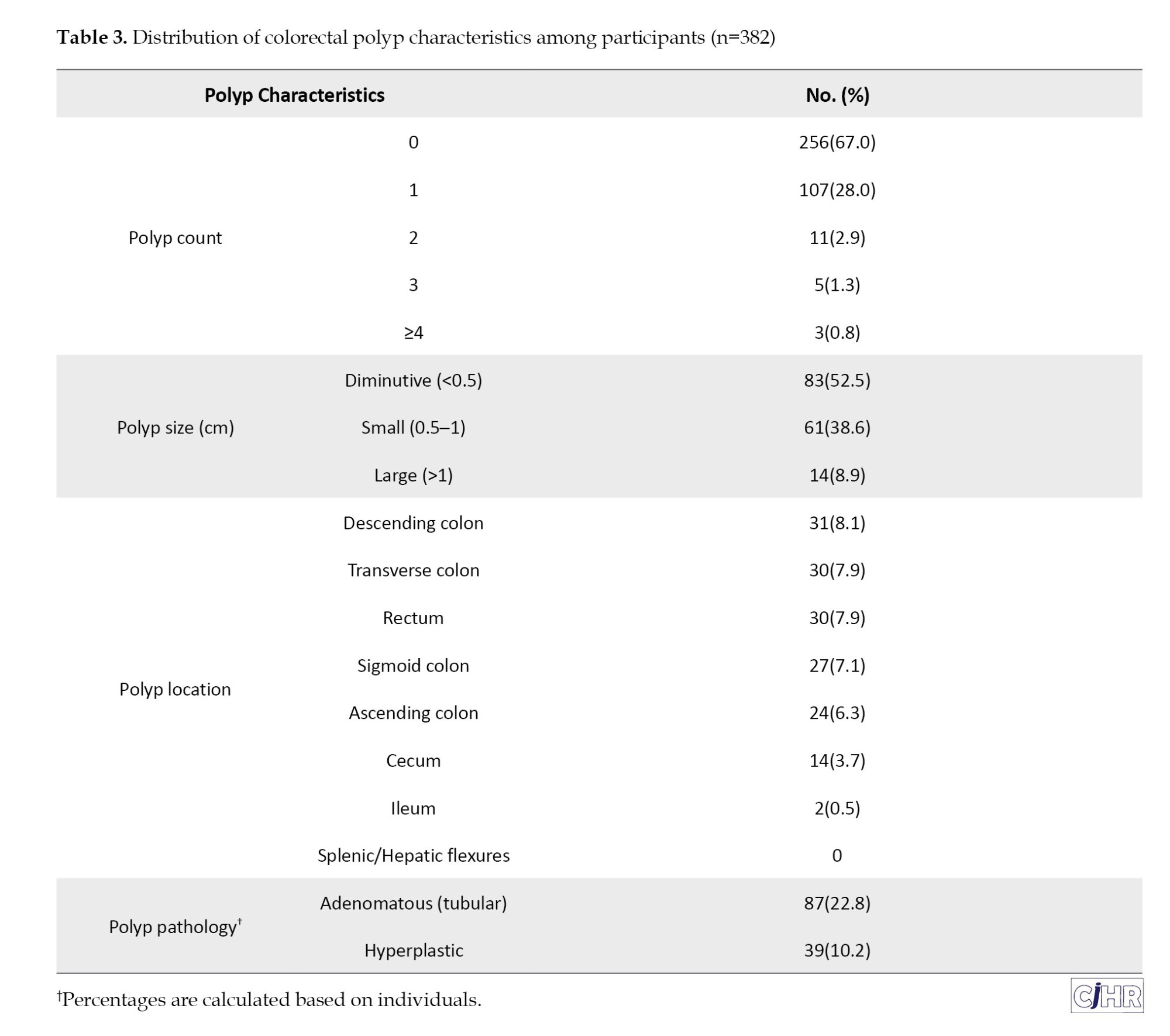

Among participants, 67.0% (n=256) had no polyps, while 28.0% (n=107) had one, 2.9% (n=11) had two, and 1.3% (n=5) had three polyps. A minority (0.8%, n=3) presented with four or more polyps (Table 3, Figure 1). In total, 158 polyps were detected among all participants. Regarding size, 52.5% (n=83) of polyps were classified as diminutive (<0.5 cm), 38.6% (n=61) were small (0.5–1 cm), and 8.9% (n=14) were larger than 1 cm. Anatomical distribution among participants showed the most frequent sites as descending colon (8.1%), transverse colon (7.9%), rectum (7.9%), and sigmoid colon (7.1%). The ascending colon, cecum, and ileum had lower frequencies, 6.3%, 3.7%, and 0.5%, respectively. Histopathologically, 22.8% (n=87) were adenomatous (tubular adenomas), and 10.2% (n=39) were hyperplastic polyps (Table 3).

Association between H. pylori infection and colorectal polyps

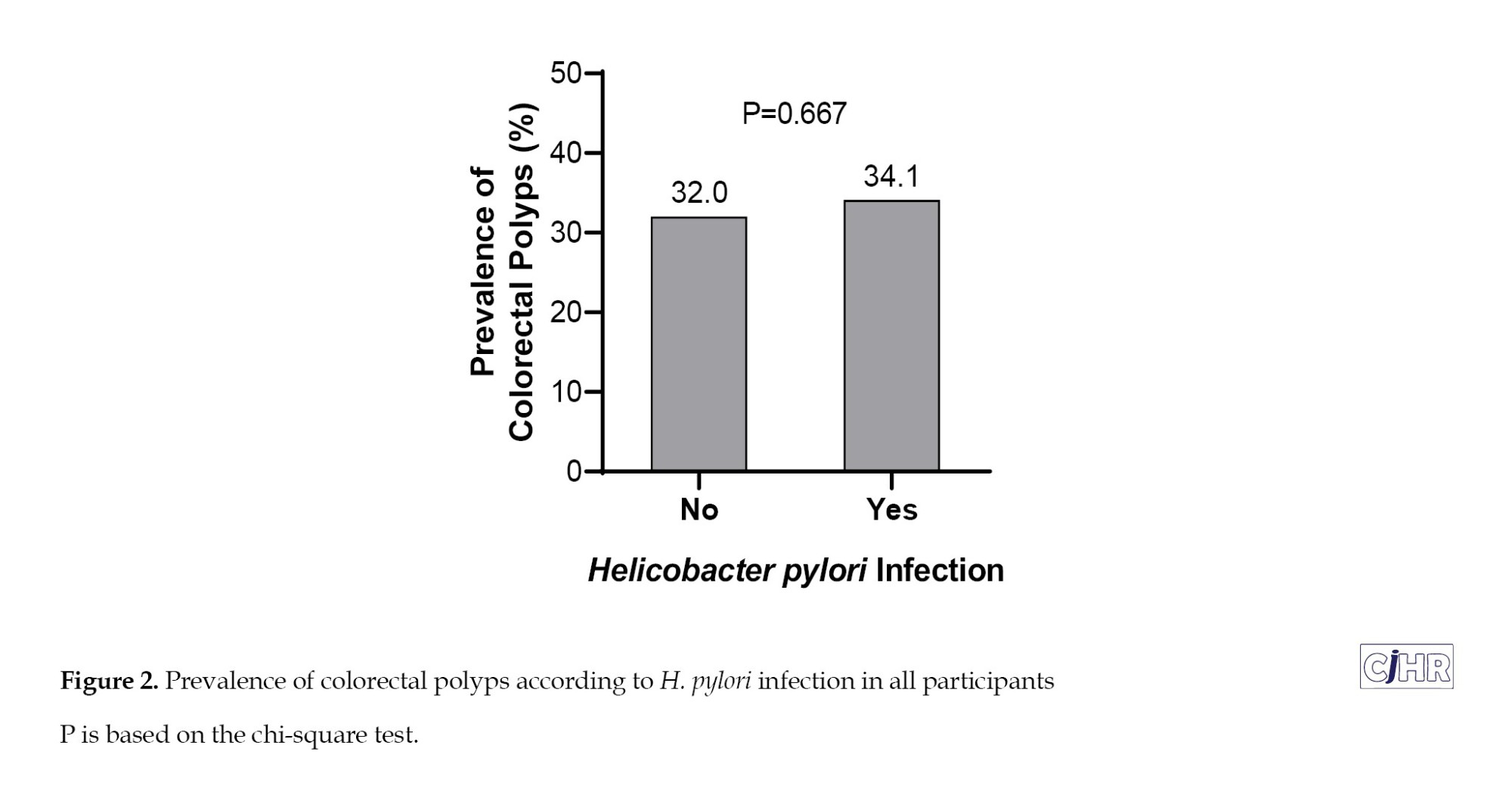

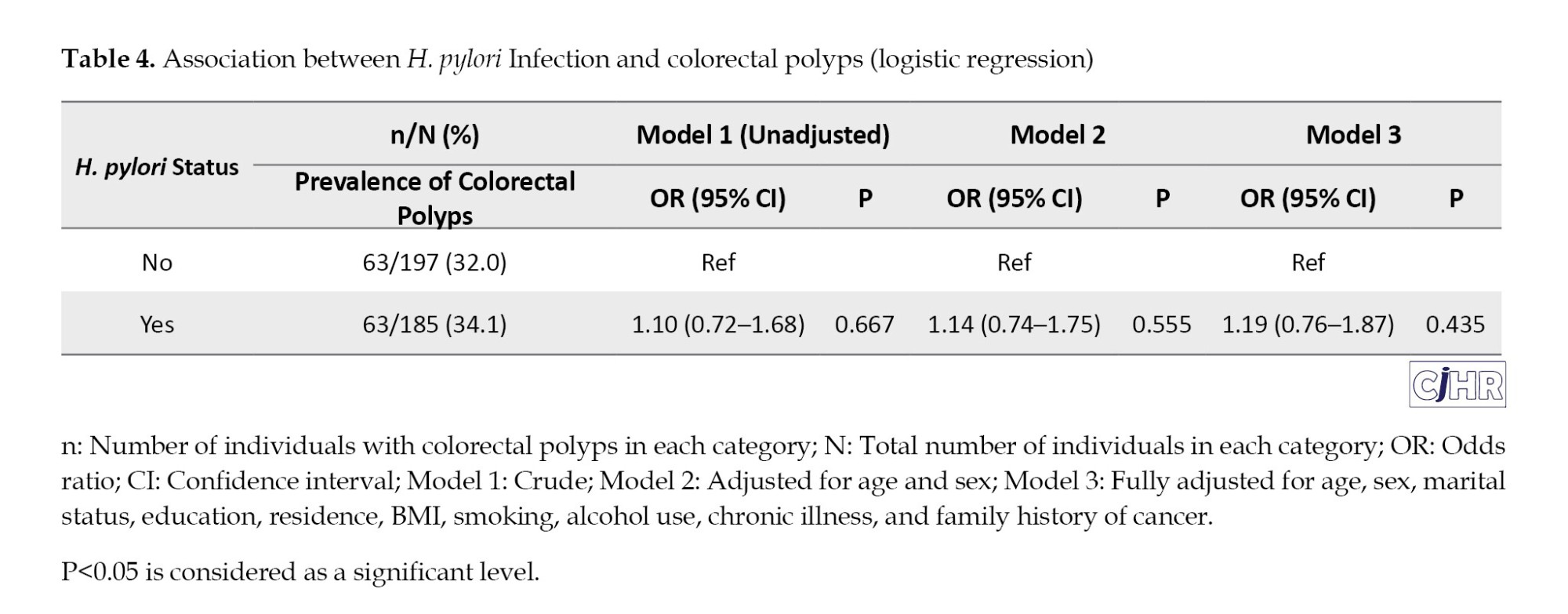

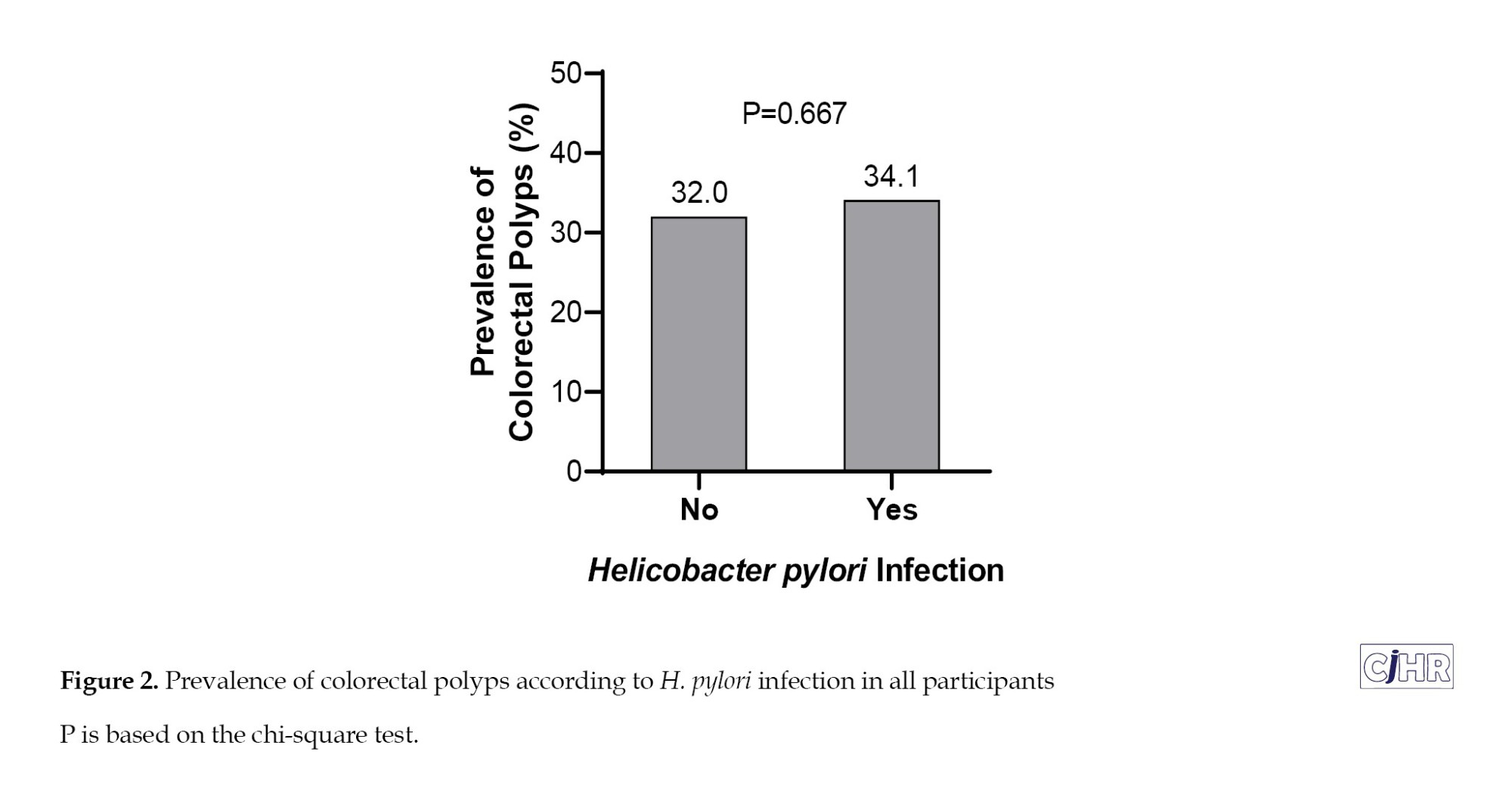

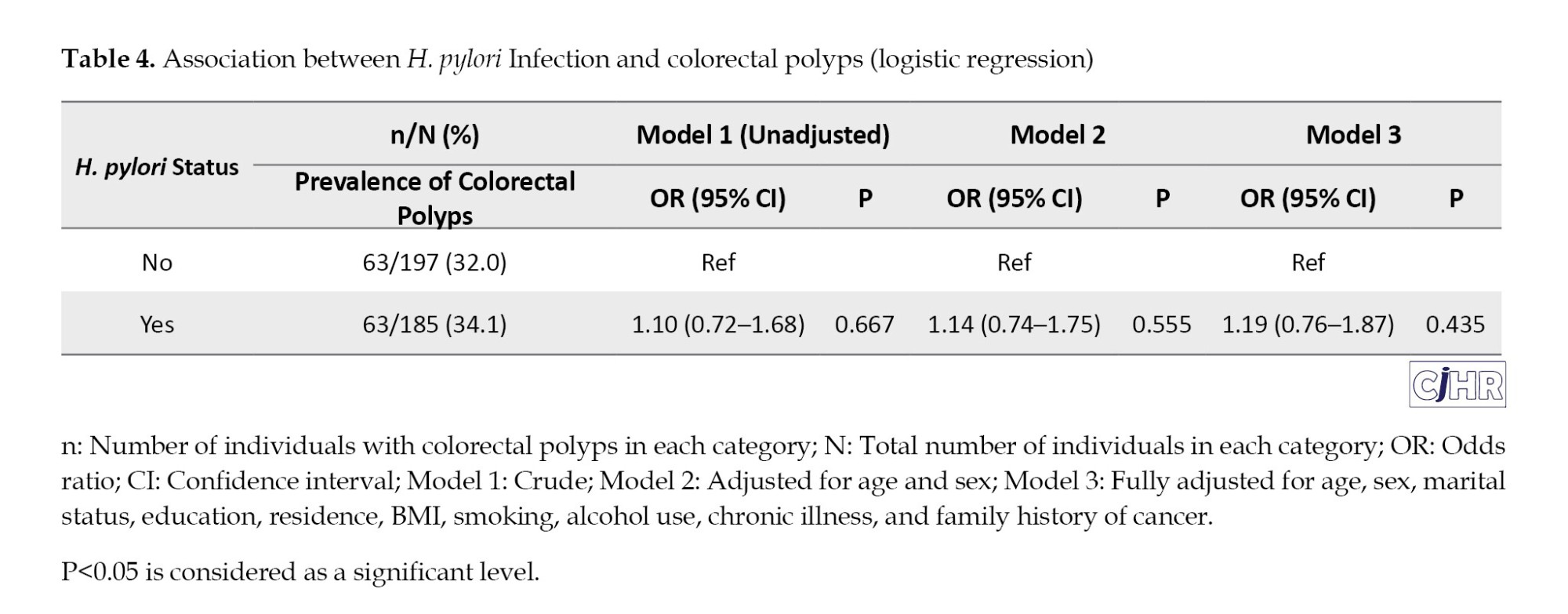

The prevalence of colorectal polyps among those with and without H. pylori infection was 34.1% (63/185) and 32.0% (63/197), respectively, with no statistically significant difference (P=0.667) (Table 4, Figure 2).

In unadjusted logistic regression (Model 1), H. pylori infection was not significantly associated with colorectal polyps (OR=1.10; 95% CI, 0.72%, 1.68%; P=0.667). After adjusting for age and sex (Model 2), the association remained non-significant (OR=1.14; 95% CI, 0.74%, 1.75%; P=0.555). In the fully adjusted model (Model 3), which included demographic and clinical variables (marital status, education, residence, BMI, smoking, alcohol use, comorbidities, and family history of cancer), H. pylori infection still did not demonstrate a statistically significant association with colorectal polyps (adjusted OR=1.19; 95% CI, 0.76%, 1.87%; P=0.435) (Table 4).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study conducted on individuals undergoing endoscopy and colonoscopy at a hospital in northern Iran, we found no statistically significant association between H. pylori infection and the presence of colorectal polyps, even after adjustment for potential confounders such as age, sex, lifestyle, and clinical factors. Our study contributed to this ongoing debate by providing evidence from a Middle Eastern population with high endemic rates of H.pylori infection. It is noteworthy that the overall prevalence of colorectal polyps in our study (33%) was consistent with other regional studies [23, 24], and that polyp prevalence increased significantly with age, reinforcing age as a principal determinant in colorectal neoplasia development. These findings validated current guidelines supporting age-based colonoscopy screening [25–27].

Although the prevalence of colorectal polyps was marginally higher among those infected with H. pylori (34.1% vs 32.0%), logistic regression analysis did not support a significant association. Our findings aligned with those of Liou et al. in Taiwan, who also reported no significant correlation between H. pylori infection and the presence of colorectal polyps in a large population-based study [13]. Similarly, Siddheshwar et al. also reported no significant association between H. pylori infection and the presence of colorectal polyps or cancer, suggesting that geographic, genetic, or microbial diversity might moderate the proposed relationship [28]. These consistent results across diverse populations suggest that H. pylori may not universally act as a risk factor for colorectal neoplasia, especially when polyp characteristics were not stratified.

In contrast, a growing number of studies report a significant association between H. pylori infection and colorectal polyps, particularly adenomatous and advanced lesions. A meta-analysis by Lu et al. including over 320,000 participants, and a cohort study by Basmacı et al. analyzing 4,561 patients, both demonstrated higher rates of H. pylori infection in individuals with total, adenomatous, or high-risk polyps (ORs ranging from 1.67 to 2.06), particularly for multiple, large, or high-risk histological types [12, 29]. These findings supported the hypothesis that H. pylori may contribute to colorectal carcinogenesis, especially in relation to advanced or high-risk polyps. The lack of association in our study might have been partly attributed to the relatively small number of high-risk polyps and absence of detailed subgroup analysis by polyp histology or multiplicity.

The potential biological mechanisms supporting a link between H. pylori infection and colorectal neoplasia are multifaceted. Chronic H. pylori infection can lead to sustained systemic inflammation and increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, which can influence epithelial cell proliferation and DNA damage beyond the gastric environment [30, 31]. Additionally, infection-associated hypochlorhydria may alter gut microbial diversity and composition, promoting dysbiosis and the production of carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds in the colon [30]. The CagA virulence factor of H. pylori has also been implicated in oncogenic pathways involving β-catenin activation and E-cadherin disruption, mechanisms relevant to colorectal epithelial transformation [32]. These mechanisms may explain why some studies report stronger associations in individuals with advanced or multiple polyps, as seen in the study by Basmaci et al. or in populations with higher inflammatory burdens [29].

A local study by Teimoorian et al. also supported the positive association between H. pylori and colorectal neoplasia, reporting significantly elevated IgG and IgA antibody titers against H. pylori in patients with adenomatous polyps and CRC compared to healthy controls [33]. Their findings, although based on serologic rather than histologic or stool antigen methods, suggested a possible systemic immune response that might be associated with colonic mucosal changes. This contrasted with our findings, where histopathological confirmation of infection did not show a statistically significant relationship. Such discrepancies highlight the influence of diagnostic modality, immune response heterogeneity, and possibly strain-specific virulence in shaping the observed outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study found no significant association between H. pylori infection and colorectal polyps in a northern Iranian population. However, this does not exclude a potential effect in subgroups, advanced lesions, or in association with specific H. pylori strains. Given the complexity of this relationship, further well-designed, multi-parameter studies are warranted to elucidate the role of H. pylori in colorectal tumorigenesis. A strength of this study was the use of standardized colonoscopy and endoscopy protocols, H. pylori detection using histology, and multivariable adjustment for potential confounders. However, a limitation of this study was the lack of detailed subgroup analysis by polyp histology, size, and multiplicity. Adenomatous and hyperplastic polyps have different risk profiles, and the omission of such stratification may mask potential subtype-specific associations with H. pylori infection. Moreover, as a single-center study with convenience sampling, generalizability may have been limited. The absence of virulence profiling (e.g. CagA, VacA) and microbiome assessment was also a notable limitation. Future studies should aim for multicenter designs with larger sample sizes and standardized criteria for polyp classification. Incorporating H. pylori strain typing and microbiome profiling could enhance understanding of host pathogen interactions. Longitudinal cohorts are needed to clarify temporal relationships between infection and neoplastic progression.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1404.086), and all participants were fully informed about the aim of the research study and the voluntary nature of participation. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

This study was extracted from a thesis for degree of gastroenterology fellow-ship thesis in Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, and Farahnaz Joukar; Data curation: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad, and Abed Pourseyedian; Formal analysis: Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad, and Saman Maroufizadeh; Investigation: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, Saman Maroufizadeh, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad, and Abed Pourseyedian; Methodology: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad, and Abed Pourseyedian; Project administration: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, and Alieh Jedinia; Resources: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, and Alieh Jedinia; Software: Saman Maroufizadeh, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, and Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad; Supervision: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, and Farahnaz Joukar; Validation: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, and Saman Maroufizadeh; Visualization: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, Saman Maroufizadeh, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad, and Abed Pourseyedian; Writing the original draft: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, Saman Maroufizadeh, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad, and Abed Pourseyedian; Review and editing: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, Saman Maroufizadeh, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad, and Abed Pourseyedian.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the subjects who participated in this research and the Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran for cooperation in data acquisition.

References

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains a major public health concern worldwide, ranking as the third most commonly diagnosed malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality [1]. Colorectal polyps, particularly adenomatous and serrated types, are well-established precursor lesions that play a critical role in the adenoma carcinoma sequence [2, 3]. Identifying and understanding the modifiable risk factors contributing to colorectal polyp formation is vital for the development of effective preventive strategies against CRC [4]. Recent research has increasingly focused on the role of gastrointestinal microbiota and chronic infections in the pathogenesis of colorectal neoplasia. Among these, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), a Gram-negative, microaerophilic bacterium that colonizes the human stomach and is implicated in chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, and gastric cancer has drawn attention for its potential association with extragastric malignancies, including CRC [5–7].

Mechanistically, H. pylori may influence colorectal carcinogenesis via systemic inflammatory responses, alterations in gastric acid secretion, changes in gut microbiota, or through the release of carcinogenic metabolites such as ammonia and N-nitroso compounds [8–10]. Epidemiological studies examining the link between H. pylori infection and colorectal polyps have yielded mixed results. Several meta-analyses and case-control studies have reported a significant association between H. pylori seropositivity and increased risk of colorectal polyps and adenomas [11, 12], whereas others have found no clear relationship [13, 14]. These inconsistencies may be attributed to variations in geographic regions, diagnostic methods, H. pylori strains, host genetic factors, and environmental exposures. Notably, studies suggest that the effect of H. pylori may be more pronounced in populations with high background infection rates and differing gut microbial profiles [6, 15, 16].

Iran, particularly its northern regions along the Caspian Sea, exhibits a relatively high prevalence of both H. pylori infection and CRC incidence compared to global averages [16, 17]. Despite this epidemiological overlap, limited population-based studies have explored the potential association between H. pylori infection and colorectal polyps in this region. Given the unique demographic, dietary, and microbial characteristics of northern Iran, investigating this relationship is both timely and regionally relevant. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the association between H. pylori infection and the presence of colorectal polyps in individuals undergoing colonoscopy in northern Iran. By identifying potential infectious contributors to colorectal polyp formation, this research may enhance our understanding of CRC risk stratification and inform tailored screening and prevention strategies in high-risk populations.

Materials and Methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted at Razi Hospital, the main gastroenterology referral center in Rasht, northern Iran between May 2024 and July 2024. All eligible individuals referred for both upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and colonoscopy were recruited using a census and convenience sampling strategy. All procedures complied with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Study population and eligibility criteria

Adults aged 18 years and older who were referred for diagnostic upper endoscopy and colonoscopy were considered eligible for inclusion in the study. Based on an expected prevalence of colorectal polyps of 34.6% [18], a 95% confidence level, and 80% power to detect an odds ratio of 1.8 for the association with H. pylori, the minimum required sample size was calculated as 370 participants. Individuals were excluded if they were unable to complete adequate bowel preparation, had a history of gastrointestinal malignancy or were under ongoing follow-up for known gastrointestinal cancers, had prior gastrointestinal surgery other than polypectomy, presented with active gastrointestinal bleeding at the time of evaluation, had used proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) without discontinuation for at least two weeks prior to endoscopy to avoid false-negative H. pylori results [19], had received antibiotics within the preceding month, or had previously undergone eradication therapy for H. pylori infection.

Data collection and instruments

Data were collected using a standardized case-report form and structured questionnaire, administered by a trained research team. The questionnaire gathered demographic (age, sex, education level, marital status, occupation), lifestyle (smoking status, alcohol consumption), clinical (underlying diseases, family history of CRC). and body mass index (BMI). Anthropometric measurements were performed by trained staff using a calibrated digital scale (Seca 803, Germany) for weight and a stadiometer for height.

Assessment of H. pylori infection

All participants underwent upper endoscopy using a standard video gastroscope (FUJIFILM, Japan). During the procedure, multiple biopsies were obtained, usually two from the gastric body and two from the antrum, for histopathological examination. The presence of H. pylori was confirmed by pathologist reports using Giemsa staining for improved detection sensitivity.

Colonoscopy procedure and polyp evaluation

Colonoscopy was performed on all subjects by gastroenterologists blinded to participants’ H. pylori status using standard colonoscopy systems (FUJIFILM, Japan). Bowel preparation involved a clear liquid diet for 24 hours, with a regimen including Bisacodyl tablets, Sena-Graph syrup, and Pidrolax powder, in accordance with local institutional protocol. Solid foods and colored liquids were avoided; antidiabetic and cardiovascular medications were managed under specialist guidance. When polyps were detected, polypectomy was performed using cold snare forceps for polyps ≤1 cm and hot snare forceps for polyps >1 cm, in accordance with established endoscopic guidelines [20, 21]. Excised specimens were placed in 10% formalin and transferred to the pathology department, which was blinded to H. pylori status.

Polyp size was determined by visual comparison with biopsy forceps and confirmed by direct measurement of the specimen with a surgical ruler. Histopathological classification was based on World Health Organization (WHO) criteria and included [22]: Tubular adenoma, tubulovillous adenoma, serrated adenoma, hyperplastic polyp, inflammatory polyp, and sessile serrated lesions . Polyps were further categorized by size: <0.5 cm, 0.5–1 cm, and >1 cm. Participants were categorized into four groups based on their H. pylori infection status and the presence or absence of colorectal polyps: Those with both H. pylori infection and polyps, those with H. pylori infection but no polyps, those without H. pylori infection who had polyps, and those without H. pylori infection and no polyps.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were reported as Mean±SD. Differences in the prevalence of colorectal polyps across sex and age groups were assessed using the chi-square test and the cochran-armitage test for trend. The prevalence of colorectal polyps among participants with and without H. pylori infection was also compared using the chi-square test. To evaluate the association between H. pylori infection and the presence of colorectal polyps, logistic regression analysis was performed in both crude and adjusted models. Results were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software, version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and a two-tailed P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism software, version 8.0.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

Participant demographics and clinical characteristics

A total of 382 individuals referred to the endoscopy unit at Razi Hospital in Rasht were included in the study. The mean age of participants was 56.93±13.51 years, with 39.3% (n=150) aged above 60 years. Women accounted for 54.5% (n=208) of the study population. The majority were married (82.7%, n=316), and 66.2% (n=253) resided in urban areas. Only 9.4% (n=36) had a university education, while 57.1% (n=218) had not completed high school. The mean BMI was 25.59±4.46 kg/m², and 15.2% (n=58) of participants were categorized as obese. Smoking and alcohol use were reported in 7.3% (n=28) and 1.3% (n=5), respectively. A total of 53.4% (n=204) had at least one underlying medical condition, and 6.8% (n=26) reported a family history of cancer (Table 1).

Prevalence of H. pylori infection and colorectal polyps

The overall prevalence of H. pylori infection was 48.4% (n=185). The prevalence did not differ significantly between men and women (49.4% vs 47.6%, P=0.722) or among age groups (48.9% in <40 years, 50.8% in 40–60 years, 45.3% in >60 years; P for trend = 0.453) (Table 2). The overall prevalence of colorectal polyps was 33.0% (n=126) (Table 2, Figure 1).

No significant sex difference was observed (33.3% in men vs. 32.7% in women; P=0.894). However, polyp prevalence increased significantly with age: 19.1% in participants <40 years, 33.5% in those 40–60 years, and 36.7% in those >60 years (P for trend=0.049) (Table 2).

Colorectal polyp characteristics

Among participants, 67.0% (n=256) had no polyps, while 28.0% (n=107) had one, 2.9% (n=11) had two, and 1.3% (n=5) had three polyps. A minority (0.8%, n=3) presented with four or more polyps (Table 3, Figure 1). In total, 158 polyps were detected among all participants. Regarding size, 52.5% (n=83) of polyps were classified as diminutive (<0.5 cm), 38.6% (n=61) were small (0.5–1 cm), and 8.9% (n=14) were larger than 1 cm. Anatomical distribution among participants showed the most frequent sites as descending colon (8.1%), transverse colon (7.9%), rectum (7.9%), and sigmoid colon (7.1%). The ascending colon, cecum, and ileum had lower frequencies, 6.3%, 3.7%, and 0.5%, respectively. Histopathologically, 22.8% (n=87) were adenomatous (tubular adenomas), and 10.2% (n=39) were hyperplastic polyps (Table 3).

Association between H. pylori infection and colorectal polyps

The prevalence of colorectal polyps among those with and without H. pylori infection was 34.1% (63/185) and 32.0% (63/197), respectively, with no statistically significant difference (P=0.667) (Table 4, Figure 2).

In unadjusted logistic regression (Model 1), H. pylori infection was not significantly associated with colorectal polyps (OR=1.10; 95% CI, 0.72%, 1.68%; P=0.667). After adjusting for age and sex (Model 2), the association remained non-significant (OR=1.14; 95% CI, 0.74%, 1.75%; P=0.555). In the fully adjusted model (Model 3), which included demographic and clinical variables (marital status, education, residence, BMI, smoking, alcohol use, comorbidities, and family history of cancer), H. pylori infection still did not demonstrate a statistically significant association with colorectal polyps (adjusted OR=1.19; 95% CI, 0.76%, 1.87%; P=0.435) (Table 4).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study conducted on individuals undergoing endoscopy and colonoscopy at a hospital in northern Iran, we found no statistically significant association between H. pylori infection and the presence of colorectal polyps, even after adjustment for potential confounders such as age, sex, lifestyle, and clinical factors. Our study contributed to this ongoing debate by providing evidence from a Middle Eastern population with high endemic rates of H.pylori infection. It is noteworthy that the overall prevalence of colorectal polyps in our study (33%) was consistent with other regional studies [23, 24], and that polyp prevalence increased significantly with age, reinforcing age as a principal determinant in colorectal neoplasia development. These findings validated current guidelines supporting age-based colonoscopy screening [25–27].

Although the prevalence of colorectal polyps was marginally higher among those infected with H. pylori (34.1% vs 32.0%), logistic regression analysis did not support a significant association. Our findings aligned with those of Liou et al. in Taiwan, who also reported no significant correlation between H. pylori infection and the presence of colorectal polyps in a large population-based study [13]. Similarly, Siddheshwar et al. also reported no significant association between H. pylori infection and the presence of colorectal polyps or cancer, suggesting that geographic, genetic, or microbial diversity might moderate the proposed relationship [28]. These consistent results across diverse populations suggest that H. pylori may not universally act as a risk factor for colorectal neoplasia, especially when polyp characteristics were not stratified.

In contrast, a growing number of studies report a significant association between H. pylori infection and colorectal polyps, particularly adenomatous and advanced lesions. A meta-analysis by Lu et al. including over 320,000 participants, and a cohort study by Basmacı et al. analyzing 4,561 patients, both demonstrated higher rates of H. pylori infection in individuals with total, adenomatous, or high-risk polyps (ORs ranging from 1.67 to 2.06), particularly for multiple, large, or high-risk histological types [12, 29]. These findings supported the hypothesis that H. pylori may contribute to colorectal carcinogenesis, especially in relation to advanced or high-risk polyps. The lack of association in our study might have been partly attributed to the relatively small number of high-risk polyps and absence of detailed subgroup analysis by polyp histology or multiplicity.

The potential biological mechanisms supporting a link between H. pylori infection and colorectal neoplasia are multifaceted. Chronic H. pylori infection can lead to sustained systemic inflammation and increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, which can influence epithelial cell proliferation and DNA damage beyond the gastric environment [30, 31]. Additionally, infection-associated hypochlorhydria may alter gut microbial diversity and composition, promoting dysbiosis and the production of carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds in the colon [30]. The CagA virulence factor of H. pylori has also been implicated in oncogenic pathways involving β-catenin activation and E-cadherin disruption, mechanisms relevant to colorectal epithelial transformation [32]. These mechanisms may explain why some studies report stronger associations in individuals with advanced or multiple polyps, as seen in the study by Basmaci et al. or in populations with higher inflammatory burdens [29].

A local study by Teimoorian et al. also supported the positive association between H. pylori and colorectal neoplasia, reporting significantly elevated IgG and IgA antibody titers against H. pylori in patients with adenomatous polyps and CRC compared to healthy controls [33]. Their findings, although based on serologic rather than histologic or stool antigen methods, suggested a possible systemic immune response that might be associated with colonic mucosal changes. This contrasted with our findings, where histopathological confirmation of infection did not show a statistically significant relationship. Such discrepancies highlight the influence of diagnostic modality, immune response heterogeneity, and possibly strain-specific virulence in shaping the observed outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study found no significant association between H. pylori infection and colorectal polyps in a northern Iranian population. However, this does not exclude a potential effect in subgroups, advanced lesions, or in association with specific H. pylori strains. Given the complexity of this relationship, further well-designed, multi-parameter studies are warranted to elucidate the role of H. pylori in colorectal tumorigenesis. A strength of this study was the use of standardized colonoscopy and endoscopy protocols, H. pylori detection using histology, and multivariable adjustment for potential confounders. However, a limitation of this study was the lack of detailed subgroup analysis by polyp histology, size, and multiplicity. Adenomatous and hyperplastic polyps have different risk profiles, and the omission of such stratification may mask potential subtype-specific associations with H. pylori infection. Moreover, as a single-center study with convenience sampling, generalizability may have been limited. The absence of virulence profiling (e.g. CagA, VacA) and microbiome assessment was also a notable limitation. Future studies should aim for multicenter designs with larger sample sizes and standardized criteria for polyp classification. Incorporating H. pylori strain typing and microbiome profiling could enhance understanding of host pathogen interactions. Longitudinal cohorts are needed to clarify temporal relationships between infection and neoplastic progression.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran (Code: IR.GUMS.REC.1404.086), and all participants were fully informed about the aim of the research study and the voluntary nature of participation. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Funding

This study was extracted from a thesis for degree of gastroenterology fellow-ship thesis in Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, and Farahnaz Joukar; Data curation: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad, and Abed Pourseyedian; Formal analysis: Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad, and Saman Maroufizadeh; Investigation: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, Saman Maroufizadeh, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad, and Abed Pourseyedian; Methodology: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad, and Abed Pourseyedian; Project administration: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, and Alieh Jedinia; Resources: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, and Alieh Jedinia; Software: Saman Maroufizadeh, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, and Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad; Supervision: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, and Farahnaz Joukar; Validation: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, and Saman Maroufizadeh; Visualization: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, Saman Maroufizadeh, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad, and Abed Pourseyedian; Writing the original draft: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, Saman Maroufizadeh, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad, and Abed Pourseyedian; Review and editing: Kourosh Mojtahedi, Fariborz Mansour-Ghanaei, Alieh Jedinia, Farahnaz Joukar, Saman Maroufizadeh, Mehrnaz Asgharnezhad, and Abed Pourseyedian.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the subjects who participated in this research and the Guilan University of Medical Sciences, Rasht, Iran for cooperation in data acquisition.

References

- El Muhtaseb MS, Ghanayem A, Almanaseer WN, Alshebelat H, Ghanayem R, Alsheikh GM, Al Karmi F, Al Aruri DO. Assessing awareness of colorectal cancer symptoms, risk factors and screening barriers among eligible adults in Jordan: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2025; 25(1):1544. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-025-22800-6] [PMID]

- De Palma FDE, D'Argenio V, Pol J, Kroemer G, Maiuri MC, Salvatore F. The molecular hallmarks of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer. Cancers. 2019; 11(7):1017. [DOI:10.3390/cancers11071017] [PMID]

- Burnett-Hartman AN, Newcomb PA, Phipps AI, Passarelli MN, Grady WM, Upton MP, et al. Colorectal endoscopy, advanced adenomas, and sessile serrated polyps: Implications for proximal colon cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012; 107(8):1213-9. [DOI:10.1038/ajg.2012.167] [PMID]

- Øines M, Helsingen LM, Bretthauer M, Emilsson L. Epidemiology and risk factors of colorectal polyps. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2017; 31(4):419-24. [DOI:10.1016/j.bpg.2017.06.004] [PMID]

- Xu W, Xu L, Xu C. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastrointestinal microecology. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022; 12:938608 [DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2022.938608] [PMID]

- Engelsberger V, Gerhard M, Mejías-Luque R. Effects of helicobacter pylori infection on intestinal microbiota, immunity and colorectal cancer risk. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024; 14:1339750. [DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2024.1339750] [PMID]

- Zumkeller N, Brenner H, Zwahlen M, Rothenbacher D. Helicobacter pylori infection and colorectal cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2006; 11(2):75-80. [DOI:10.1111/j.1523-5378.2006.00381.x] [PMID]

- Butt J, Epplein M. Helicobacter pylori and colorectal cancer-A bacterium going abroad? PLoS Pathog. 2019; 15(8):e1007861. [DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1007861] [PMID]

- Rahman MM, Islam MR, Shohag S, Ahasan MT, Sarkar N, Khan H, et al. Microbiome in cancer: Role in carcinogenesis and impact in therapeutic strategies. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022; 149:112898. [DOI:10.1016/j.biopha.2022.112898] [PMID]

- Baj J, Forma A, Sitarz M, Portincasa P, Garruti G, Krasowska D, et al. Helicobacter pylori virulence factors-mechanisms of bacterial pathogenicity in the gastric microenvironment. Cells. 2020; 10(1):27. [DOI:10.3390/cells10010027] [PMID]

- Wang M, Kong WJ, Zhang JZ, Lu JJ, Hui WJ, Liu WD, et al. Association of helicobacter pylori infection with colorectal polyps and malignancy in China. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020; 12(5):582-91. [DOI:10.4251/wjgo.v12.i5.582] [PMID]

- Lu D, Wang M, Ke X, Wang Q, Wang J, Li D, et al. Association Between H. pylori infection and colorectal polyps: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Front Med. 2022; 8:706036. [DOI:10.3389/fmed.2021.706036] [PMID]

- Liou JM, Lin JW, Huang SP, Lin JT, Wu MS. Helicobacter pylori infection is not associated with increased risk of colorectal polyps in Taiwanese. Int J Cancer. 2006; 119(8):1999-2000. [DOI:10.1002/ijc.22050] [PMID]

- Ajdarkosh H, Tameshkel FS, Sohrabi MR, Niya MHK, Hemmasi G, Amirkalali B, et al. Association of helicobacter pylori infection with colon polyp and colorectal cancer. Br J Med Med Res. 2016; 16:1-6. [Link]

- Kuo YC, Ko HJ, Yu LY, Shih SC, Wang HY, Lin YC, et al. Kill two birds with one stone? the effect of helicobacter pylori eradication in decreased prevalence of gastric cancer and colorectal cancer. Cancers. 2024; 16(22):3881. [DOI:10.3390/cancers16223881] [PMID]

- Hosseini E, Poursina F, de Wiele TV, Safaei HG, Adibi P. Helicobacter pylori in Iran: A systematic review on the association of genotypes and gastroduodenal diseases. J Res Med Sci. 2012; 17(3):280-92. [PMID]

- Mohebbi M, Mahmoodi M, Wolfe R, Nourijelyani K, Mohammad K, Zeraati H, et al. Geographical spread of gastrointestinal tract cancer incidence in the Caspian Sea region of Iran: spatial analysis of cancer registry data. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:1-12. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2407-8-137] [PMID]

- Matin S, Joukar F, Maroufizadeh S, Asgharnezhad M, Karimian P, Mansour-Ghanaei F. The frequency of colorectal lesions in the first-degree relatives of patients with colorectal lesions among PERSIAN Guilan Cohort Study population (PGCS). BMC Gastroenterol. 2024; 24(1):88. [DOI:10.1186/s12876-024-03177-z] [PMID]

- Laine L, Estrada R, Trujillo M, Knigge K, Fennerty MB. Effect of proton-pump inhibitor therapy on diagnostic testing for Helicobacter pylori. Ann Intern Med. 1998; 129(7):547-50. [DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-129-7-199810010-00007] [PMID]

- Kudo T, Horiuchi A, Horiuchi I, Kajiyama M, Morita A, Tanaka N. Pedunculated colorectal polyps with heads ≤ 1 cm in diameter can be resected using cold snare polypectomy. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2021; 84(3):411-415. [DOI:10.51821/84.3.008] [PMID]

- Copland AP, Kahi CJ, Ko CW, Ginsberg GG. AGA clinical practice update on appropriate and tailored polypectomy: Expert review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024; 22(3):470-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.cgh.2023.10.012] [PMID]

- Zhu C, Wang Y, Zhang H, Yang Q, Zou Y, Ye Y, et al. Morphology, Histopathology, and Anatomical Distribution of Sporadic Colorectal Polyps in Chinese Patients. Gastro Hep Adv. 2023; 2(7):964-70. [DOI:10.1016/j.gastha.2023.06.002] [PMID]

- Mousavian AH, Sadeghi A, Kasaeian A, Rayatpisheh M, Nikfam S, Malek M, et al. Colorectal polyp prevalence and adenoma detection rates in an Iranian cohort: a prospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025;25(1):1-6. [DOI:10.1186/s12876-025-04032-5] [PMID]

- Iravani S, Kashfi SM, Azimzadeh P, Lashkari MH. Prevalence and characteristics of colorectal polyps in symptomatic and asymptomatic Iranian patients undergoing colonoscopy from 2009-2013. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014; 15(22):9933-7. [DOI:10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.22.9933] [PMID]

- Ejtehadi F, Taghavi AR, Ejtehadi F, Shahramian I, Niknam R, Moini M, et al. Prevalence of colonic polyps detected by colonoscopy in symptomatic patients and comparison between different age groups. What age should be considered for investigation? Pol Przegl Chir. 2023; 96(1):15-21. [DOI:10.5604/01.3001.0053.3997] [PMID]

- Vilkoite I, Tolmanis I, Abu Meri H, Polaka I, Mezmale L, Lejnieks A. Age-based comparative analysis of colorectal cancer colonoscopy screening findings. Medicina. 2023; 59(11):2017. [DOI:10.3390/medicina59112017] [PMID]

- Li X, Hu M, Wang Z, Liu M, Chen Y. Prevalence of diverse colorectal polyps and risk factors for colorectal carcinoma in situ and neoplastic polyps. J Transl Med. 2024; 22(1):361. [DOI:10.1186/s12967-015-0718-3] [PMID]

- Siddheshwar RK, Muhammad KB, Gray JC, Kelly SB. Seroprevalence of Helicobacter pylori in patients with colorectal polyps and colorectal carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001; 96(1):84-8. [DOI:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03355.x] [PMID]

- Basmaci N, Karataş A, Ergin M, Dumlu GŞ. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and colorectal polyps. Medicine. 2023; 102(42):e35591. [DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000035591] [PMID]

- Li Q, Geng S, Luo H, Wang W, Mo YQ, Luo Q, et al. Signaling pathways involved in colorectal cancer: pathogenesis and targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024; 9(1):266. [DOI:10.1038/s41392-024-01953-7] [PMID]

- White JR, Winter JA, Robinson K. Differential inflammatory response to Helicobacter pylori infection: Etiology and clinical outcomes. J Inflamm Res. 2015; 8:137-47. [DOI:10.2147/JIR.S64888] [PMID]

- Yong X, Tang B, Xiao YF, Xie R, Qin Y, Luo G, et al. Helicobacter pylori upregulates Nanog and Oct4 via Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway to promote cancer stem cell-like properties in human gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2016; 374(2):292-303. [DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.032] [PMID]

- Teimoorian F, Ranaei M, Tilaki KH, Shirvani JS, Vosough Z. Association of Helicobacter pylori infection with colon cancer and adenomatous polyps. Iran J Pathol. 2018; 13(3):325. [PMID]

Article Type: Original Contributions |

Subject:

Health Management

Received: 2025/07/10 | Accepted: 2025/08/7 | Published: 2025/10/1

Received: 2025/07/10 | Accepted: 2025/08/7 | Published: 2025/10/1

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |